24 reasons why China’s ban on foreign trash is a wake-up call for global waste exporters

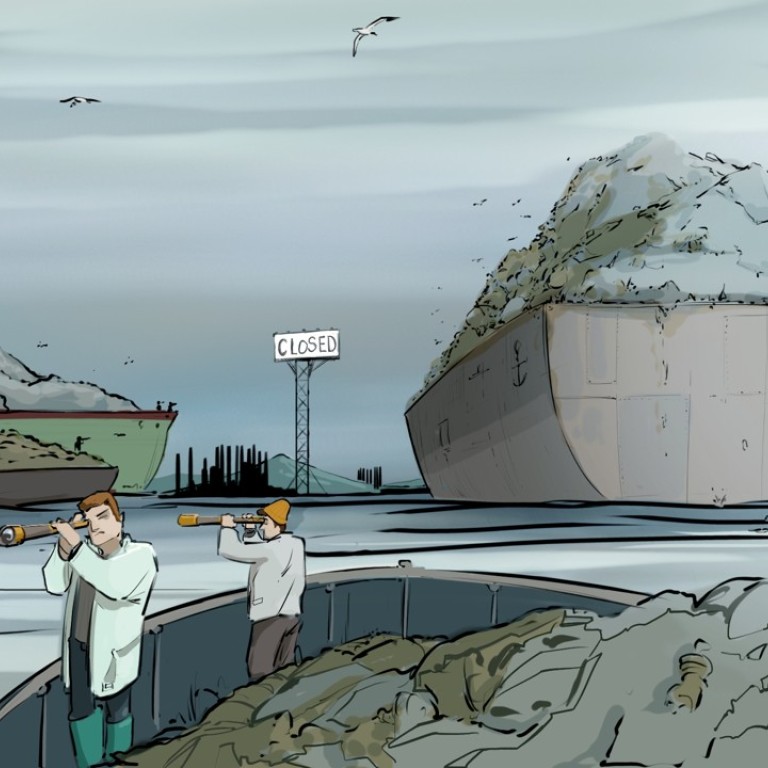

Tom Baxter and Liu Hua say China’s refusal to remain the dumping ground for foreign garbage highlights the need for countries to start facing up to their plastics addiction, and for makers of plastics and disposable goods to take responsibility for the environmental damage inflicted

Though the regulation is primarily designed to address major environmental and health issues in China, it will also be a genuine global disrupter. It has the potential to propel many waste-exporting countries – who for far too long have taken an “out of sight, out of mind” attitude to waste disposal – to adopt far more progressive disposal and recycling systems.

Since the 1980s, China has become the world’s largest importer of waste, or “foreign trash”, as it is commonly called in Chinese. By 2012, up to 56 per cent of global exported plastic waste ended up in China.

Watch: Guiyu, once the world’s e-waste capital

The award-winning documentary, Plastic China, released last year, showed in painful detail that the serious health and environmental consequences of the foreign waste trade have been far from just limited to scandals like Guiyu.

Watch: Plastic pollution is choking the world

The tiny plastic pollutants that end up on your dinner plate

As with any “crisis”, however, the waste disposal problems the UK and other countries are set to face as a result of the new ban is also an opportunity to find more sustainable means of dealing with waste.

China’s ban could push countries to tackle wasteful, disposable lifestyles at source

Ultimately, the ban could push countries to tackle wasteful, disposable lifestyles at source, by forcing plastics and other disposable goods manufacturers to take responsibility for the environmental damage caused by their products throughout their whole life cycle. For plastic bottles, for example, the life cycle from production to decomposition can be up to 450 years.

There are fears that the ban will simply lead to these huge quantities of waste being exported to less developed, less well-regulated waste industries, especially in Southeast Asia. In fact, UK exports of waste to Vietnam and Malaysia doubled in 2017, compared to 2016. However, there are no new waste markets with equivalent capacity to China’s over the last three decades.

This globally disruptive event, then, leaves governments little alternative but to face up to the reality of their waste problems.

Watch: Trailer – ‘Plastic China’

For China’s own part, now that the imports of these 24 types of waste have been banned, the enormous recycling and manufacturing sector will be short of millions of tonnes of plastic waste supply every year.

China plastic demand to rise as foreign waste ban curbs recycling

As a result, the whole sector will become hungrier for domestic waste supplies, which could act as a major stimulus for China’s own waste management and recycling.

The onus will now be on governments across the country to introduce more comprehensive and more effective waste classification measures, to ensure more gets recycled, and less gets dumped in rapidly expanding landfill sites.

The world should wake up when China finally says no to being the global refuse dump

The start of 2018 marks a hugely disruptive moment for global trash, and the aftershocks of this will be felt across the world for months to come. This moment will also, however, force waste-exporting markets to find better solutions for their waste disposal. The new regulation on an often overlooked multibillion-dollar global industry could well be a key turning point in global waste generation and disposal.

The world cannot continue with the current wasteful consumption model based on infinite growth in a finite world

The world cannot continue with the current wasteful consumption model based on infinite growth in a finite world. The new era is not just about effective recycling, it is also about tackling our waste problem at source, by drastically reducing the production of billions of plastic goods every year.

Industries and corporations that manufacture and market huge amounts of disposable plastics need to take responsibility for their products through their entire life-cycle, take responsibility for the environmental costs, and invest in transformative solutions and alternatives that will stop the current flood of waste into our lives.

It’s time to wave goodbye to the “out of sight, out of mind” attitude towards waste, and usher in an era of reduced waste. Governments across the world will soon realise they have little choice but to welcome this new era, for the good of our and our planet’s health.

Tom Baxter is a communications officer at Greenpeace East Asia. Liu Hua is Greenpeace East Asia’s plastics campaigner