How long does China’s President Xi Jinping plan to hold power? Here’s the magic number

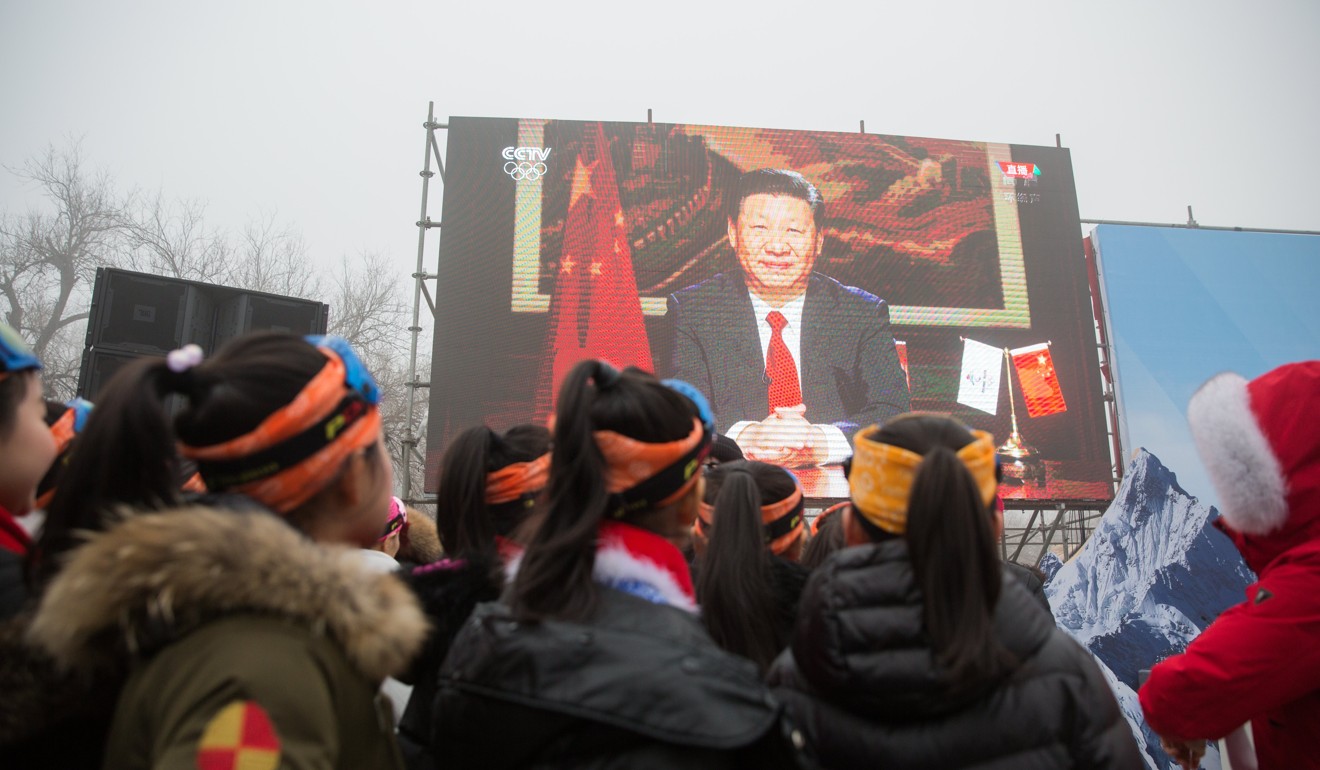

The removal of term limits on the Chinese presidency gives special meaning to Xi Jinping’s self-imposed schedule for restoring China to its rightful place as a world power

Xi’s confidence in moving Deng’s schedule forward 15 years now takes on a special meaning and provides an intriguing indicator of how long he plans to be in power given the latest announcement.

Speculation about Xi’s future has been growing since he declined to anoint an heir apparent in the party’s new leadership line-up unveiled immediately after the congress, marking a break from a succession system of peaceful power transfers which first took place in 2002.

Xi’s no Mao … or Deng … or Chiang – so who is he?

Many observers originally believed Xi would signal his intention much later in his second term, which would have seen him further tighten his grip on power.

The fact that he has revealed his hand just as his second term has started highlights not only his dominance but also the urgency with which he must advance his agenda given his self-imposed deadline to restore China to its rightful place as a world power.

In fact, of the trinity of leadership positions Xi has held, the presidency is largely a ceremonial role – albeit one that carries hugely symbolic significance. Xi’s two other more important positions – as the party’s general secretary (for which he was given his second term of five years at the 19th congress) and as the chairman of the armed forces – carry no term limits. But the state constitution limits the presidency to two terms totalling 10 years and Xi will begin his second term in March.

Revising the constitution to remove the two-term limit would greatly strengthen the legitimacy of Xi’s power just as the Chinese leadership drums up efforts to promote the rule of law.

What an unlimited Xi presidency means for China’s neighbours

Just one day before the constitutional changes were made public on Sunday, Xi chaired a Politburo meeting to stress the important role of the constitution. “No organisation or individual has the privilege to overstep the constitution or the law,” he was quoted as saying.

In the five years since he came to power in 2012, Xi has completely overhauled China’s governance system and the armed forces partly though the unprecedented anti-corruption campaign and tightened the party’s control over all aspects of society at home.

WATCH: The South China Sea – what has happened so far?

Recently, many analysts have compared Xi’s stature to that of Mao Zedong or Deng Xiaoping. But Mao and Deng commanded authority and loyalty through decades of struggles and wars and forming bonds of flesh and blood with other Chinese leaders. By contrast, Xi’s first five-year reign may have boosted his personal authority and sidelined his political foes but he is still faced with an uphill and long-term struggle to transform the Chinese economy and succeed in taming corruption.

As a result, a 20-year theory has gained traction among some analysts who gaze into their crystal balls regarding Xi’s political future, drawing from the reigns of previous generations of leaders going all the way back to the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949.

The true test for President Xi will be when China’s luck runs out

From 1949, Mao remained the undisputed leader of the country until his death in 1976, giving him a reign of 27 years. In 1979, Deng became China’s paramount leader and maintained his influence as the spiritual leader until his death in 1997, a total of 18 years.

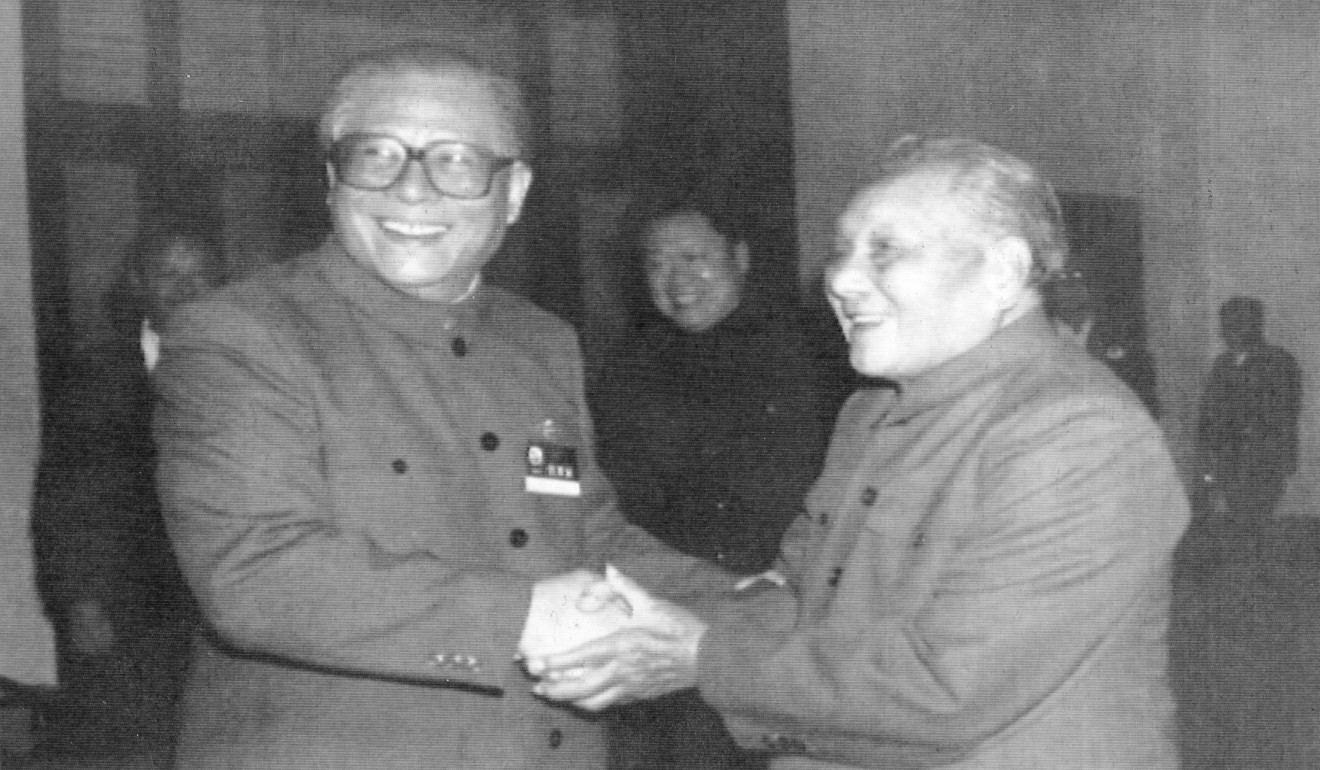

Deng installed Jiang Zemin as the party chief in 1989 and later allowed him to assume the trinity of leadership positions which also included the presidency and the chairmanship of the armed forces. But Jiang’s era only started in 1997 following Deng’s death. Although he fully retired in 2004 and made way officially for Hu Jintao, he remained the final arbiter of power throughout Hu’s 10-year reign until the latter’s retirement in 2012. That gave Jiang an effective reign of 15 years.

Born in 1953, Xi will be 82 by 2035. By comparison, Deng was 85 when he fully retired in early 1990.

Is keeping Xi Jinping in power the answer to China’s economic woes or a recipe for disaster?

Of course, it is entirely possible that Xi could follow Mao’s example to rule until his death but given the hard lessons China has learned from Mao’s era, this scenario is unlikely. Indeed, an editorial by the hawkish Global Times newspaper, while applauding the decision to remove the two-term limit for the presidency, quoted an authoritative person as saying the change did not mean the Chinese president would have a lifelong tenure.

It is worth pointing out that Xi’s confidence in promoting China’s ways of developing its economy with authoritarian rule and without espousing Western values – a model known as “socialism with Chinese characteristics” – comes at a time of profound international change in which Western democracies are on the retreat and autocracies are on the rise.

For China, a fine line between ‘Great Leader Xi’ and ‘Xi, the great leader’

While foreign media have largely portrayed the proposed change to term limits as a power grab by Xi, perhaps a more interesting question is whether Xi’s rising power will benefit the country’s development and improve the well-being of the people.

After Xi’s five years of impressive governance, his vision of leading China to national rejuvenation has won him popular support among the party’s rank and file and convinced many he is the leader to take the country forward in the next 15-20 years.

Others will have to resign themselves to the historic loop from which China has yet to break free in its thousands of years of history: the well-being of the entire country will be at the mercy of a benevolent leader.

Xi’s key message has been that as the party tightens control over all aspects of society, it will do whatever it can to fulfil the Chinese people’s aspirations for a better life in exchange for the legitimacy to maintain authoritarian rule at home.

Chinese and foreign investors may welcome the political stability Xi’s autocratic rule will bring, so long as he delivers what he and his allies have promised – that is, to undertake reforms and market-opening measures which could exceed “international expectations”.

First term limits ... now Xi Jinping to shake up the state to tighten Communist Party’s grip on government

Of course, dangers lurk ahead for Xi, not the least because if he centralises too much power in his own hands his subordinates may no longer dare to inform him of uncomfortable truths, which could lead to lopsided judgments and policy blunders.

Another worry is that as he takes the credit for all progress, he will likewise have to take blame for everything that goes wrong, which could put excessive pressure on policymaking.

As China is in the painful process of transforming its economy, there are plenty of chances for things to go terribly wrong.

Inevitably, Sunday’s announcement has further alarmed the country’s intellectuals who are already worried about the massive propaganda campaign that has been building a personality cult around Xi over the past few years.

Despite the authorities’ vigilance in removing from the internet and social media platforms any criticisms of the proposed constitutional amendment, many people still find ways to make their views known.

Some have dug out earlier warnings by Deng and Jiang about the dangers of lifetime appointments and of predicating the stability of the country and party on the authority of one or two individuals.

In ending presidential term limits, ‘Xi Jinping is thinking global and acting local’

When Putin first came to power in 2000, he reportedly vowed to restore Russia to its past glory within 20 years. Nearly 18 years later, the Russian economy has shrunk significantly, partly because of falling commodity prices and Western sanctions.

The irony is that despite the dismal economic performance – and allegations of mismanagement and corruption against some of Putin’s cronies – the Russians look set to return him to the Kremlin for a fourth term. ■

Wang Xiangwei is the former editor-in-chief of the South China Morning Post. He is now based in Beijing as editorial adviser to the paper