Exclusive | China’s probes on Fosun, HNA and others unleash the power of the unsaid word

The unusual loan check ordered by Beijing and political rumours cast a cloud over investors’ interests on China’s top overseas acquirer

In China, the biggest risk comes not from what’s been said, but what’s unsaid.

Four of China’s biggest offshore asset buyers – Anbang, Fosun, HNA Group and Wanda – were placed under regulatory scrutiny since mid-June, causing the prices of companies linked to them to plummet.

Even though nothing amiss was found, and regulatory sources and bank officials were at pains to stress that there’ll been no change in risks, some investors are getting cold feet.

The latest drama unfolded on Thursday, when Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical Group, the flagship drugmaker of the Fosun Group, plunged as much as 7 per cent in Hong Kong and 8.9 per cent in Shanghai, after word got around on some Chinese news portals that the conglomerate’s founder and chairman Guo Guangchang had been “unreachable,” a euphemism to imply that the person had been detained for investigations.

Guo had indeed been unreachable, only because he’d been in Xi’an delivering a speech. His return flight to Shanghai was delayed -- he flew commercial as his private jet was under maintenance -- due to air traffic congestion.

Fosun issued two statements denying anything untoward, and UBS AG had to organise a conference call with analysts and investors just to hear Guo’s voice, as he put paid to the rumours. The call, beamed out live on a video streaming site, was watched by more than 1,000 people simultaneously.

It was the second time in a month that Fosun had been struck by rumours. On June 22, Fosun’s shares along with those Wanda, plunged on speculation that the CBRC was checking up on their loans, while the companies were affected by “political risks.”

“The arbitrariness in which people are detained in China with no transparency or legal process leads to such a market response,” said Fraser Howie, a former banker in Asia who has co-written three books on the Chinese financial system. “All these big companies are in the spotlight as part of the clampdown on financial risk, but we are all in the dark as to what is really going on. Is it anti-corruption? Abuse of cross-border flows, illegal financing? Wasteful investment? We just don’t know.”

What is known is that as it is with everything else in China, privately owned enterprises -- which contribute to 60 per cent of China’s economy, half of the nation’s tax receipts and generates 80 per cent of jobs -- still operate under the good graces of the ruling Communist Party, almost at the party’s pleasure.

The party’s crackdown on graft has snared at least 12 senior cadres in the first half of 2017, including the insurance regulator Xiang Junbo. Of the four tycoons under scrutiny, Wang Jianlin of Wanda and Chen Feng of HNA are Communist Party members.

“The party respects no legal boundaries when it acts,” Howie said. “The government claims the market is to be the decisive factor, yet even for private companies, the party seems to be taking a pretty direct interest.”

The four have more than US$10 billion worth of syndicated loans and bonds that will mature by 2019, according to Bloomberg’s data.

“Large-scale investments made by private companies in China “should be fine,” said Li Daokui, a Tsinghua University professor and former advisor to the Chinese central bank’s monetary policy committee, in an interview with CNBC. “Those investment they made in the past two years were done in a highly intense political environment. They were already very careful to begin with, so I do not think there will be major or widespread cases of misconduct at the end of the investigation.”

The South China Morning Post spoke to two of the founders of the four companies about their borrowings and the financial health of their companies:

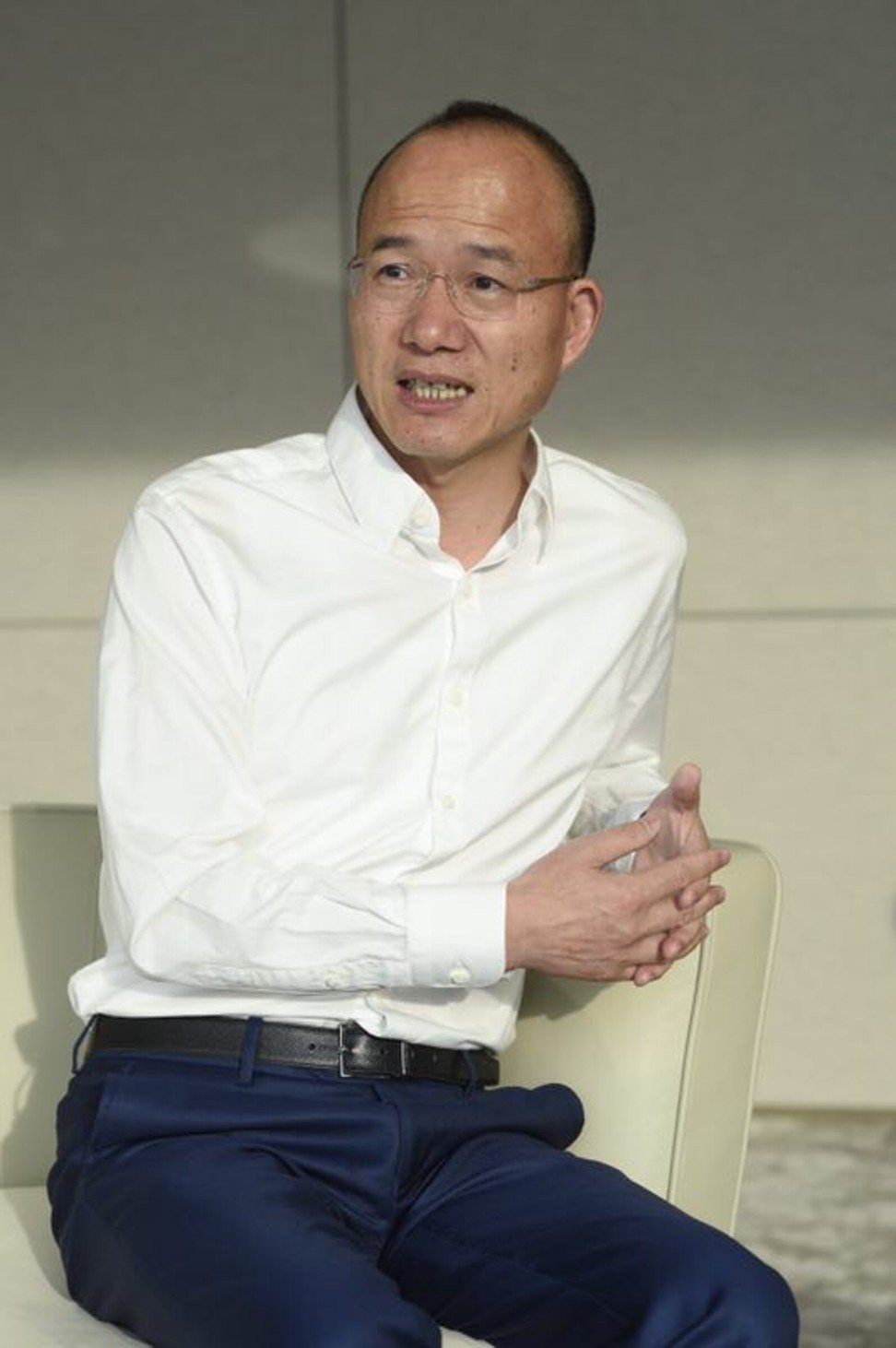

Guo Guangchang -- Fosun Group

Guo Guangchang, founder and chairman of Chinese conglomerate Fosun Group, said his company’s debt has continued to fall as funding sources improve both locally and overseas, leaving his firm in a better financial health than other leading private enterprises in China.

“Compared with many private enterprises, even those better-performing private enterprises, we are financially more stable,” Guo said in a Thursday interview at Fosun’s Shanghai head office, overlooking the city’s waterfront.

“I am very satisfied with our financial health in terms of falling gearing ratio and improved debt structure,” Guo said.

He noted that Standard & Poor’s had raised its credit rating on Fosun, in move that he said reflected its improved balance sheet.

Fosun’s gearing had dropped to 50.7 per cent at the end of 2016, from 53.6 per cent in 2015. Financing costs have fallen from 5.7 per cent per annum in 2013 to 4.5 per cent per annum last year, he said. Last year, profit grew 27.7 per cent to 10.27 billion yuan (US$1.51 billion).

“Our ongoing operations are steady and robust. We have had a good 2016 and we expect to have an even better 2017,” he said.

Guo founded the company in 1992 along with four other graduates of Fudan University, initially as a health care company and later expanding into insurance and real estate.

In the next 10 years, Guo said the company will focus its strategy on a mission to pursue health, happiness and wealth to the rapidly emerging middle class in China.

“Fosun’s mission is creating a happiness ecosystem,” Guo said.

Chen Feng -- HNA Group

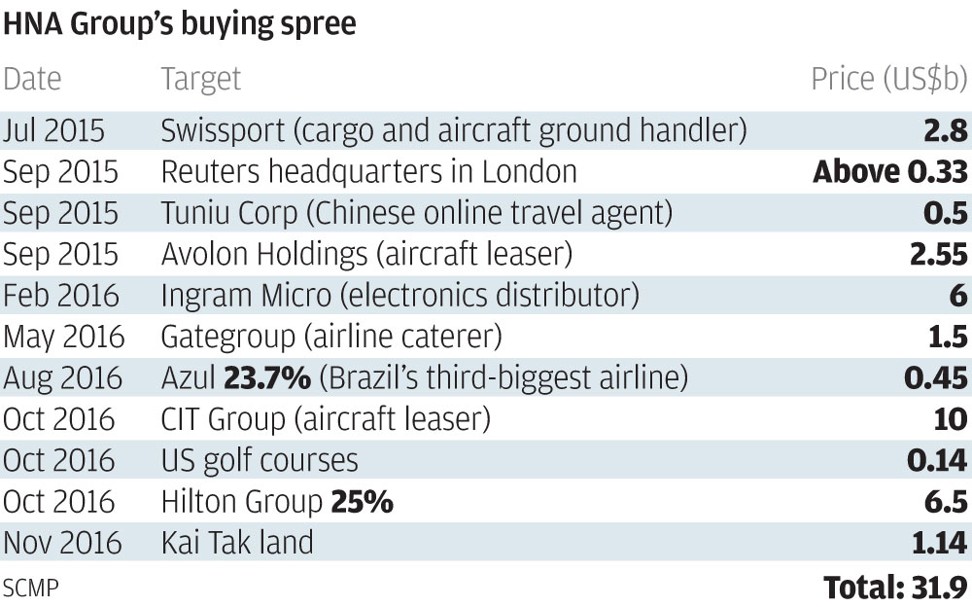

Driving the group’s shopping spree and zeal for size is founder Chen Feng, a former civil aviation official. The company has spent at least US$32 billion since 2015 in acquisitions, from a 25 per cent stake in Hilton Hotels to Chinese online travel group Tuniu Corp. to Reuters’ London building.

“In more than 20 years of doing business, HNA has had relationship with more than 300 banks in and out of China,” he said. “Every bank chairman or president knows how to reach me personally, and there’s been no problem whatsoever.”

HNA Holdings, whose credit rating was rated AA+ as of 2016, received a US$300 million unsecured loan from Morgan Stanley, proof of the company’s creditworthiness, Chen said. The company’s gearing ratio had been declining for five consecutive years, he said.