Exclusive | China’s stock market needs to ditch its patchwork rules for a clean start at its watershed moment

- After 28 years spearheading China’s four-decade experiment with capitalism, the capital market has reached a watershed moment

Investment bankers and financial consultants spent the past few weeks furiously working to turn Chinese President Xi Jinping’s November 5 blockbuster announcement of a new technology board on the Shanghai Stock Exchange into reality.

The ambitious, but sketchy, plan seeks to entice China’s most innovative start-ups to raise funds at home by adopting a registration system just like in developed markets, where initial public offerings (IPOs) can be launched based on financial needs, investors’ sentiment and market conditions.

Financial officials are hoping that Xi’s registration system could stem the exodus of China’s largest technology companies – including this newspaper’s owner Alibaba Group Holding, Baidu, Tencent Holdings and Xiaomi – to offshore markets for funds, even as they earn most of their income in China.

But bankers quickly ran into a wall: China’s regulator imposes ceilings on IPO valuations on the Shanghai and Shenzhen markets, leaving room for prices to rise when stocks debut so the country’s retail investors can profit.

The president’s tech-board diktat comes at a watershed moment for China’s stock market, which has ballooned into the world’s second-largest in the 28 years that it has spearheaded the Communist Party’s four-decade experiment with capitalism.

Where China’s US$5.6 trillion capital market heads next – back to the founding principle where the capital markets must serve the nation’s socialist development, or let the free market finds its own way – is enormously important, not just to China, but to the entire world.

“Only if Beijing abandons its top-down approach and introduces a market-driven approach will Chinese markets be able to catch up with the leading international markets,” said Francis Leung Pak-to, the “Father of Red Chips” who helped the first Chinese state-owned companies raise capital in Hong Kong in 1993, during a recent interview with the South China Morning Post.

A glimpse of the future direction could be seen in July, when the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) tried unsuccessfully to arm twist smartphone maker Xiaomi to sell a Chinese version of depositary receipts (CDRs) in Shanghai so that mainland investors could also partake in the spoils of what was then billed as the biggest global IPO of 2018.

In truth, the CDR and Xi’s latest tech board are variants of the same plan, not just to give local investors direct stakes in the biggest and most innovative Chinese companies, but also a bold attempt to turn the patchwork of regulations into something more robust. Beijing officials have been working on the strategy ever since Alibaba took its US$25 billion IPO – still the record holder as the world’s largest stock sale – to New York in 2014.

The two episodes underscore Beijing officials’ iron grip over the markets, even if they pay lip service to sweeping changes, further liberalisation and opening up.

But that iron grip will not be easy to loosen. Deng Xiaoping, the architect of China’s capitalist reforms, famously told his comrades that they needn’t fear their dalliance with markets, even to the extent of reviving the very epitome of capitalism that was shut as soon as the communists took over in 1949.

“We should not be worried about making mistakes,” Deng said. “We can close [the stock exchange] and reopen it later … We can control the pace for opening and closing, thus there is nothing to fear about.”

Shanghai’s stock exchange can trace its history to 1891 as an association of equity traders during the Qing dynasty’s twilight years.

Formally named in 1904, the early bourse was a market for banks, railways, utilities and textile mills, and even the then-Nationalist government, to sell stocks and bonds. When the communists took over Shanghai in 1949, the first order of the day was to seal off the stock exchange and arrest the traders.

When Deng kicked off his economic reforms in 1978, he needed a fundraising avenue for state factories and industries to modernise. With wounds still fresh from the Cultural Revolution that had ended two years earlier, there was little appetite – let alone any financial, accounting, regulatory or legal expertise – for creating a capitalist market.

The idea would take another decade to take shape, until the April 1988 proposal by two US-educated Chinese scholars Gao Xiqing and Wang Boming sowed the seed for the revival of China’s modern capital market.

Subsequently, a dozen policy papers were assembled, proposing Beijing as the preferred location for Communist China’s first stock market. But plans were disrupted by the military’s crackdown on protesters in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in June 1989.

Amid heightened political tension, the mantle passed to then Shanghai mayor and commissar Zhu Rongji to offer pre-revolution China’s financial hub – birthplace of such global companies as HSBC and AIG – as the alternative site for the market’s revival.

Zhu moved fast, pushing his three-men project team to commence trading a year from their appointment. He moved so fast that the Shanghai exchange did not even have its own building, and the team had less than six months to find a location. In the end, they leased a ballroom at the Astor House Hotel near the Shanghai Bund to use as its trading hall.

“Crossing the river by feeling the stones” was a frequent aphorism for describing the pragmatism in China’s embrace of capitalism, a quality that was abundant among the Shanghai exchange’s planners. For the first five years, the bourse was a “Securities” exchange in English, because of lingering ideological concern that the full embrace of “stocks” was a line too far to cross.

The change was made only after enough equities had been listed, and the exchange moved out of Astor House to its current premises.

And in a stroke of defiance, planners chose to use red to illustrate gains and advances on the exchange, while depicting losses and declines in green, the exact opposite of worldwide convention.

The Shanghai exchange reopened in December 1990, followed by a second bourse six months later in Shenzhen, a fishing village that Deng had wanted to use as a test bed for private enterprise and capitalism.

Shanghai Pudong Development Bank, a state lender formed to finance the establishment of a new financial and industrial area on the eastern banks of the Huangpu River, would be the first of eight stocks to list first in the city, with the ticker 600001.

Shenzhen Development Bank, the forbear of today’s Ping An Bank, was the first stock to trade in the southern bourse with the ticker 000001. When the Shenzhen Stock Exchange opened for trading in July 1991, crowds fought to enter a lottery to own shares. Cane-wielding police had to use cattle prods to beat back the get-rich frenzy.

The frenzy turned feverish after Deng’s epic 1992 tour of southern China, aimed at kicking start an economic reform programme that had shown signs of stalling.

By 2015, the Chinese had registered as many as 100 million stock-trading accounts, surpassing the entire Communist Party’s membership.

Shanghai’s benchmark Composite Index would reach its second historic high in 2015, just before plummeting 40 per cent over the next 10 weeks to wipe US$5 trillion of value off the market, a rout that many brokers, banks and companies are still struggling to recover from.

Concerned by the enormity of the losses, the financial authorities threw everything at the market’s yawning hole, from redundant circuit-breaking rules to closing the entire market, to amassing state funds in a so-called National Team to mop up unwanted shares.

They also arrested any trader, broker, banker or official who played too hard and fast with financial rules, or who strayed too close to the edge.

The dragnet reached even to the market regulator’s upper echelon, with former vice-chairman Yao Gang sentenced to 18 years in jail and fined 11 million yuan for accepting bribes and insider trading.

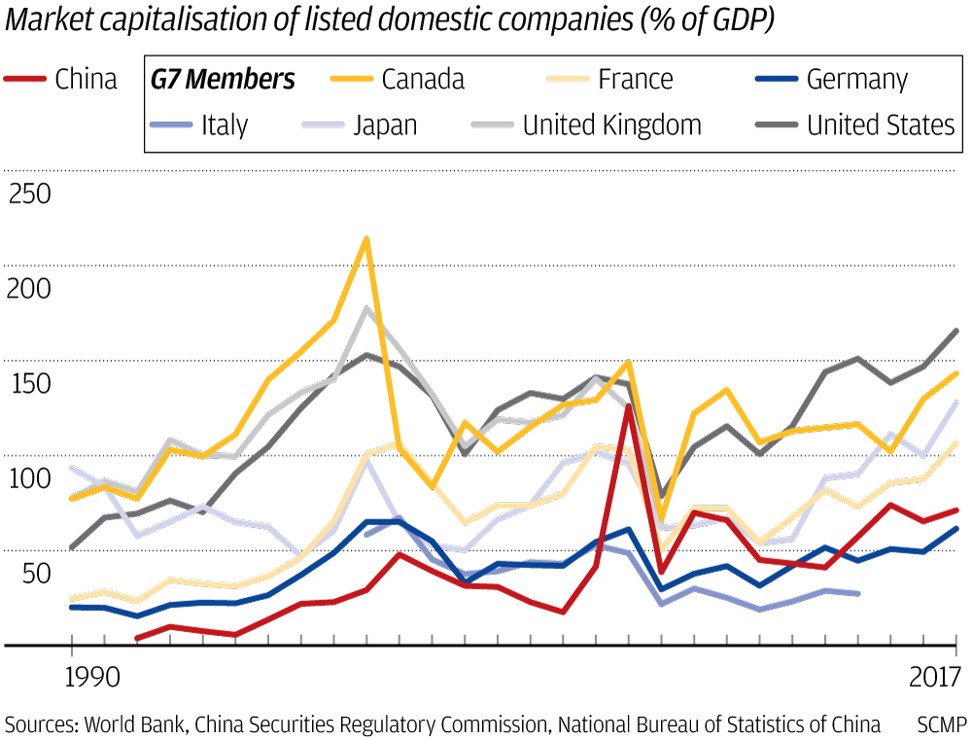

The combined capitalisation of Shanghai and Shenzhen overtook Japan’s market a decade ago to become the world’s second-largest, until they were mauled by the bear market in August and returned Asia’s pole position to Tokyo.

Being big hasn’t been beautiful. Shanghai’s key Composite Index is down almost 22 per cent this year, languishing as one of the world’s biggest losers, while Shenzhen’s benchmark has plummeted 29.6 per cent.

The reason for the malaise is China’s stock market is infested with what the Chinese regulator’s Chief Adviser Anthony Neoh called zombie companies.

These companies, more often state-owned than privately held, stay on China’s stock exchanges even if many of them are financially insolvent, or are unprofitable, because of concerns that their expulsion would lead to mass unemployment, which could disrupt social stability.

The CSRC does have delisting rules on its books, but only 60 companies have been kicked off the market since 2001.

China must “let the zombie companies die” and allow for the possibility of investors to lose money, said Neoh.

“Most people believe the government and the regulator will rescue the market,” he told the Post. “So they tend to over-leverage and take excessive risks for high returns.”

The Chinese capital market’s founding principle was its role in developing a socialist economic system, not profiteering for profit’s sake, said Zhang Ning, who helped establish the Shanghai bourse, speaking to Xinhua News Agency.

Short-selling, where traders profit by selling stocks before buying them back at lower prices, was initially banned, and later designed to be too cumbersome and insignificant to create a natural hedge against risk.

That essentially turned the entire stock market into a one-way bet, a dangerous place to be when sentiments are fragile, or money is in short supply.

“Risk and rewards are just not properly aligned,” said Fraser Howie, co-author of Red Capitalism: The Fragile Foundation of China’s Extraordinary Rise. “That leads to lack of trust within the markets, which means everyone is a short-term speculator.”

That partly explains why overseas investors held 3.2 per cent, or 1.28 trillion yuan, of China’s market capitalisation at the end of June, even with channels like Stock Connect and Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors (QFII) for accessing the yuan market, according to China Merchants Securities data. Foreign capital made up 24 per cent of US market capitalisation, and 30 per cent of Japan’s value at the end of 2017.

These policy tweaks, littered along China’s road to financial reform, do not fundamentally alter the capital market’s current course to nowhere, bankers said.

What the Chinese market needs at this watershed moment was to retire some of the most sacrosanct principles from three decades ago and start with a clean slate that is more commensurate with China’s current economic and financial needs, bankers said.

“The major problem of the Chinese stock market it that everything comes from the orders of the top leaders,” says “Father of Red Chips” Leung. “The brokers and investment banks are just following the orders from the top to execute. The mainland stock market is not driven by market forces.”