China’s long march for the soul of the nation’s digital future faces an ever-shifting end point

Chinese semiconductor companies are up against a formidable Intel-Microsoft alliance that has ring fenced an eco-system and peripheral sub-sectors of hardware producers, chip designers, software and app developers

In China’s quest for the soul of the nation’s digital technology, Ni Guangnan and Cheng Xu are two of the foot soldiers of a two-decade march to develop an indigenous semiconductor processor and operating system – a journey where the end point is ever-shifting.

Ni, the 79-year-old academic at the Chinese Academy of Engineering, led the 1999 team that developed China’s very first home-built chip. Cheng, director of the Peking University’s Microprocessor Research and Development Centre (MPRC) led the team that produced the architecture for the UniCore 16 embedded microprocessor the same year, the first building blocks of a functioning computer.

However, these engineering feats never did achieve their intended commercial adoptions, leaving Ni and Cheng to continue toiling in relative obscurity.

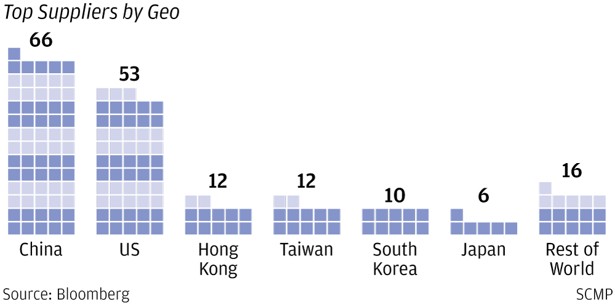

Chinese companies already claim several superlatives in 21st century technology, including the largest maker of phone equipment and the dominant platform for online shopping, as well as electronic payments. But the core components of all these companies are made by either Intel or Qualcomm, and the operating systems at the heart of their applications are by Google’s Android unit in smartphones, or Microsoft for computers.

Chinese technology for the central processing unit (CPU) of desktop and laptop computers is about 10 years behind world leaders, said Ni, who invented the world’s first hardware card for Chinese character inputs in Lenovo’s computers.

“The ZTE incident exposed how [others] can easily have a stranglehold on our industry chain,” Ni said during the May 17 World Intelligence Congress in Tianjin, according to a quote by state-owned The Paper.

China’s technological edge is in e-commerce, the internet, mobile payment systems and big data, while areas like chip design and fabrication, and the development of operating systems were key weaknesses that were “controlled by others,” Ni said.

It wasn’t for want of trying. The Chinese government set up the first semiconductor research institute as early as 1960. By the late 1970s, the country had 600 factories churning out integrated circuit boards, but at a combined annual scale that was a mere 10 per cent of what a single Japanese factory produced in a month.

In 2000, Grace Semiconductor Manufacturing was set up with much fanfare, opening a US$1.63 billion chip fabrication foundry in Shanghai. Led by Jiang Mianheng, the elder son of then Chinese president, and Winston Wang, the eldest scion of Taiwan’s wealthiest man at that time, the venture was also invested by Hong Kong’s Cheung Kong and Hutchison Whampoa.

But Grace didn’t report its first profit until 2016 – and even then had the figure combined with another Shanghai foundry called Hua Hong – and would be merged with Hua Hong in 2011.

Chen Jin, then a professor at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, hogged the headlines in 2003 with his breakthrough in microchip design, unveiling a digital signal processing chip he dubbed the Hanxin, or Chinese chip, which rhymes with “Chinese soul”. It didn’t take long for Hanxin to be exposed as a fraud, when a whistle-blower revealed that Chen had merely sanded down Motorola chips he imported from his former employer to pass off as his own innovation.

“It’s likely to take years, or even generations, of hard work for Chinese developers to catch up with the international leaders,” said Milton Lu, operations director of PhotonIC Technologies, a chip design start-up in Shanghai’s Zhangjiang Hi-Tech Park.

Still, the soul searching offers Chinese engineers the golden opportunity to rev up their research and production, said Lu, whose integrated photonic-electronic chips for next-generation optical networking and internet of things (IoT) sensing systems are used by clients including Huawei and ZTE.

“Chinese companies are now fully aware of the strategic importance of making high-end chips,” he said. “Capital and talent, the two key elements for the industry’s growth, can be expected, buoyed by the ambitions of establishing China’s own developed integrated circuit industry.”

Intel, surpassed by Samsung in 2017 as the world’s largest maker of memory chips, produced its first silicon wafer in 1969.

By the turn of the second millennium, it had accumulated a 32-year technological head start on its nearest rival, in an industry where a foundry that takes two years to build becomes technologically obsolete as a new generation of chips is introduced over the same time span.

Money and talent aside, Chinese companies also need an ecosystem of applications and partners to make up for the lost time.

“A China-designed CPU will also need an operating system” that can “make sure existing software applications like Microsoft’s Word or Excel can run smoothly,” said Mei Lingchuan, a US-based senior engineer at Jupiter Networks.

This leads to one of the industry’s biggest struggles: convincing users to adopt the full suite of home-grown architecture, where there are incompatibility risks with global systems, software programmes and applications.

Companies operate on commercial principles that bring them profits. In the business of chips and operating systems, stability and cost matter more than nationalist pride or patriotic duty. Lesser adopted home-grown technologies have not withstood the test of time, that in turn assure reliability and economies of scale that makes adoption attractive.

In 2001, Ni’s team produced the “Fangzhou 1” embedded chip. But commercial use of the chip was a herculean task, according to a blog post by Ni’s assistant Liang Ning.

China’s top electronic makers were unanimously lukewarm to adoption: they did not have the means to develop products around an original CPU architecture, because all the products developed based on Intel chips had a quicker path to market.

Cheng’s MPRC faced a similar plight. UniCore ran on an independent architecture based on the free Linux operating system, but could not get any commercial adoption, even after China in May 2014 banned the use of Microsoft’s Windows 8 OS on government computers.

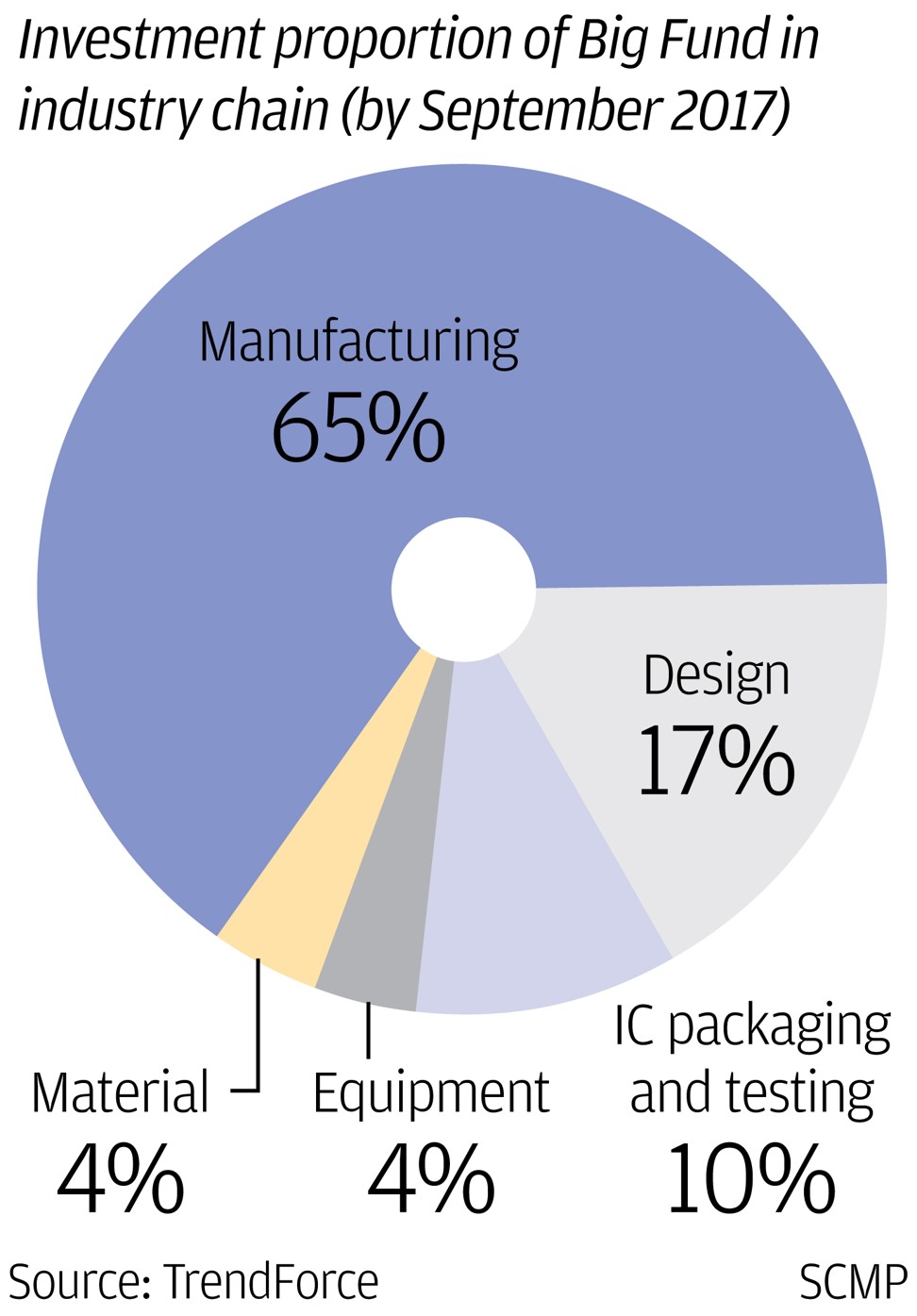

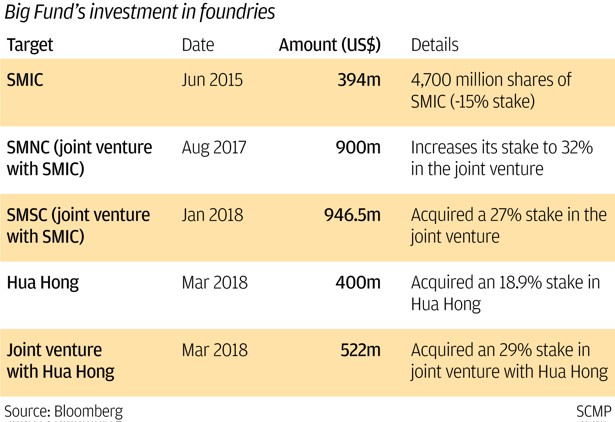

Still, what China lacked in talent and technology, could be bought. In 2014, China launched the China Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund, known in the industry as the Big Fund, in another major push to nurture innovations in the industry.

The fund has already invested about 140 billion yuan (US$22 billion) in four years, with 70 per cent of that total committed to projects within the semiconductor and digital technology supply chain. A second fund of between 150 billion yuan and 200 billion yuan is near completion, aimed at boosting Chinese chip production and technologies to wean companies off imports.

China’s global foreign direct investment amounted to US$213 billion in 2016, a fifth of which was spent in the US, with cumulative investments in the US exceeding US$100 billion since 2000, the study said.

Under President Xi Jinping, China aims to become a tech superpower and artificial intelligence global leader by 2030. The plan involves tax breaks and concessions to Chinese firms, as well as requiring foreign companies to provide key details about their technology to local partners.

While the home-grown CPU hasn’t reached critical mass to become mainstream, there are signs of progress. Shanghai Zhaoxin Semiconductor, a venture between the Shanghai government and VIA Technologies, claimed it had developed the first domestic x86 CPU micro-architecture that is compatible with all existing software, including Windows 10. Being partially owned by VIA means it is likely covered by VIA’s cross-licence agreement for x86 with Intel.

PhotonIC also saw encouraging signs of a rapid growth in the coming years since a number of investors have approached it for discussions about new rounds of financing.

China’s biggest technology companies Huawei Technologies, Alibaba Group and Tencent Holdings – with the world’s biggest research budgets between them – are also in on the race to develop chips. Alibaba is owner of the South China Morning Post.

Huawei’s premium system-on-chip (SoC) Kirin 980 top-end chip is expected to start mass production this quarter. An SoC is an electronic integrated circuit that contains various electronic components commonly including the CPU, graphical processing unit, RAM memory, ROM memory and modem.

Alibaba last month bought Hangzhou C-SKY Microsystems, a Chinese designer and developer of embedded CPUs.

Despite the recent activities, China is still lagging, at least for now.

“There’s no solution for the CPU problem. Intel is too powerful,” said state-owned Tsinghua Unigroup’s co-president Yu Yingtao in an interview with state media two weeks ago . “Ninety-five per cent of the money goes to Intel. Servers worldwide are working for it … this is the reality. On the one hand we are furious, on the other hand we are also helpless.”

With additional reporting by Xie Yu in Hong Kong.