To see how climate change is up close and very personal, look no further than Mangkhut’s havoc

- If we are to absorb the awesome, awful consequences of climate change and global warming, it has to be local and personal; like living through Mangkhut

It has been five weeks now, since Typhoon Mangkhut wreaked havoc across Hong Kong. Still, the scars are raw, and not just a matter of a few tens of thousands of trees gone.

If we are to properly absorb what climate change is all about, we need to look around us now. For most of the world’s 7 billion-plus people, climate change is not about whether global mean temperatures will be 1.5 degrees or 2 degrees higher, or about sea levels rising 10 centimetre more than previous models, or the melting of the ice cap over Greenland, or even the bleaching of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef.

If we are to absorb the awesome, awful consequences of climate change and global warming, it has to be local and personal; like Mangkhut.

Over the past two weekends, I have walked afresh along Hong Kong’s devastated high mountain trails. The shock is not the tree wreckage - though that is gruesome. The shock is the silence. Most bird life seems to have gone, and with it the birdsong, hopefully not for good. The butterflies that normally splash colour along the way are wholly absent.

As I relive the shocking 24-hour assault of Mangkhut on my village home in Clear Water Bay, I am forced to wonder how on earth our birds and butterflies managed the battering, with nowhere to hide.

From my home, I look down on a six-foot wall of wood and flotsam pushed inland by Mangkhut. The rubbish ranges from bits of boats and mangled surfboards to refrigerators and plastic everything. It sprawls a length of 40 yards (36.5 metres) and sits drying in the sun about 30 yards inland from the coastal wall that Mangkhut wrecked. Locals have by now stopped picking through it in the hope of finding something lost.

This is climate change up close and personal. Now that the sea wall has been wrecked, any old spring tide, or grumpy storm, is set to eat away the waterfront land.

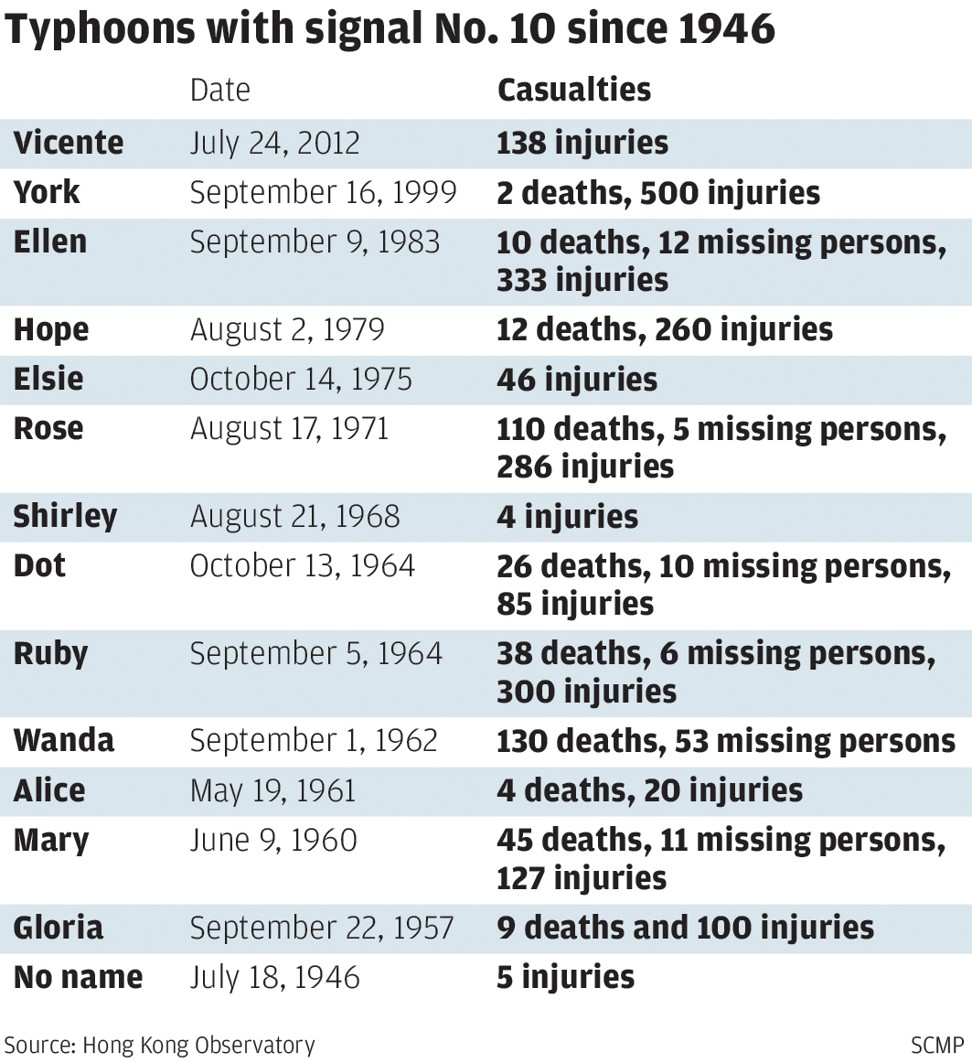

Sceptics like Donald Trump - who deny the link between human hyper-consumption, carbon dioxide emission and climate change - would argue that violent storms are not a recent phenomenon. Look at Typhoon Wanda, whose 5-metre surge left 130 dead and thousands homeless in Tai Po and Sha Tin, and which remains the deadliest storm to hit this city in seven decades.

Hong Kong’s sea levels are 15cm higher today than they were in 1962. Heaven knows what harm Wanda would have done if it passed through today.

Our weather scientists haven’t told us whether Mangkhut was more vicious than Wanda.

What they did tell us in a 2010 Hong Kong Observatory report was nevertheless blunt: “On the basis of a pessimistic but not unrealistic estimate of the sea-level rise made in recent years, even ordinary spring tides would be sufficient to bring sea flooding to low-lying areas - with or without typhoons. Mitigation measures would be necessary.”

Mitigation measures means sea walls. In the wake of Wanda, as our planners built our new towns in the 1960s and 70s, they mandated sea defences at least three metres high in all flood prone areas. One must today wonder whether than was enough, and how much needs urgently to be spent on existing sea walls, both in Victoria Harbour, and in remote Sai Kung villages like mine.

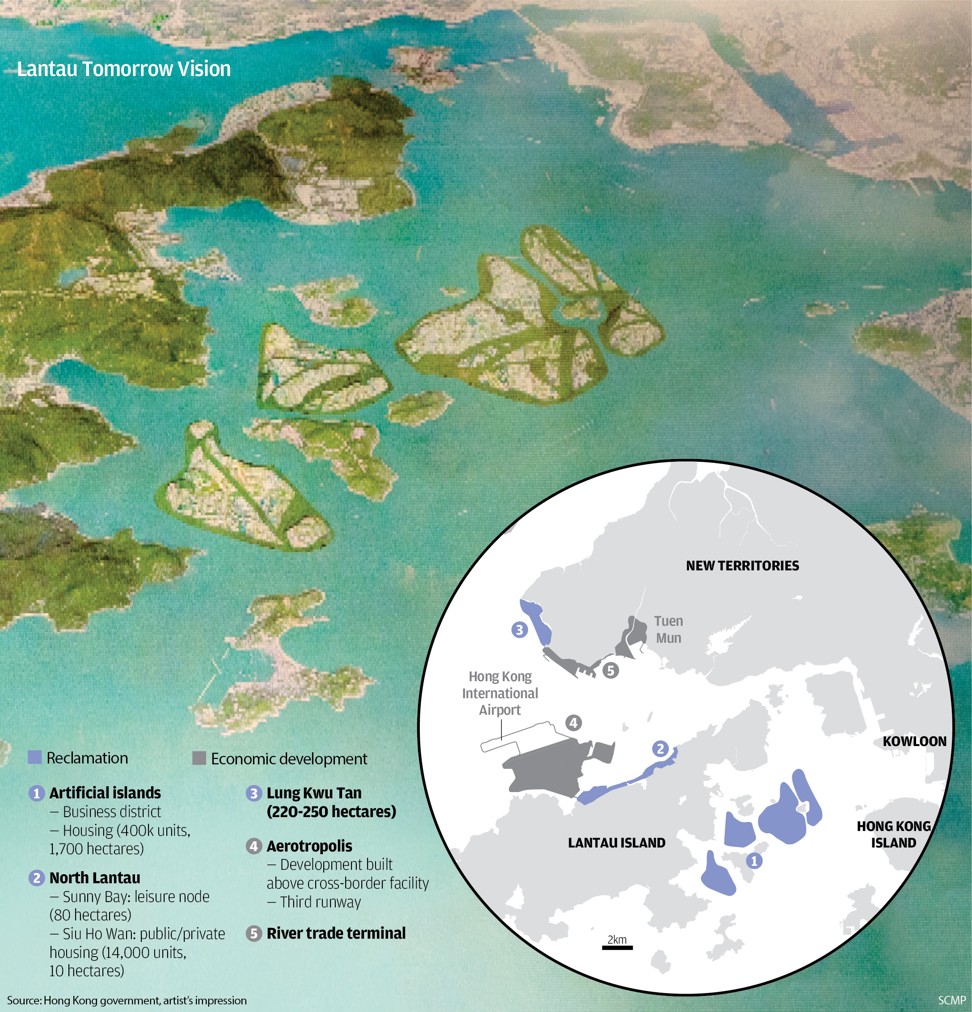

One also wonders whether Carrie Lam, as she begins to draw up plans for an ambitious new HK$500 billion (US$64 billion) man-made island off Lantau, needs to add a couple of extra metres - and an extra few hundreds of billions of dollars - to give proper protection to the one million or more people she plans to house there.

But my main point is that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and its reports, expert and thorough as they are, mean nothing if they do not capture what climate change means for us all, locally and personally.

No wonder Anjana Ahuja, the Financial Times’ science commentator, complained two weeks ago that “the international silence was deafening” following the latest IPCC report: “Climate change denial, no longer a credible political position, has given way to climate change indifference... there is little political bandwidth for a massive problem that is global in nature.”

She should add “... and unlikely to get serious until after most of our present-day political leaders are long dead.”

In Japan, it means a 2018 summer of alternating typhoons and heatwaves - with an earthquake or two added in for good measure.

In Germany and Switzerland it means the drought-hit River Rhine - the 1,200 kilometre economic lifeline for a large part of central Europe - withering to a trickle, with ferry and barge services being suspended.

It means Swiss families having to tap emergency stockpiles of diesel as fuel barges are stranded. BASF, the German chemicals group, had to halt production at the world’s largest integrated chemicals facility in Ludwigshafen.

In China, it means the Gobi desert gobbling up 3,600 square kilometres of grassland every year (the entirety of Hong Kong is just 2,754 sq km) in a country that is already desperately short of cultivable land, while sea-level rises threatens inundation of at least 1,150 sq km along China’s coast (the worst is the Pearl River Delta area, where 13 per cent of the land is already below sea level).

If the IPCC is to capture anyone’s attention - most important, the attention of our political leaders who are under constant pressure to appease spending pressures from local lobbies - its messages need to be local and personal.

The messages need to be based on our actual experiences, not on abstract mathematical models and high-level global data that bounces around our brains and settles nowhere.

I need to hear the silence of the mountain trails, and see the drab absence of butterflies, and the bleached mountains of debris straggled across my village’s destroyed sea walls.

These are the warnings of what climate change is all about. They are the warnings we cannot ignore.

David Dodwell researches and writes about global, regional and Hong Kong challenges from a Hong Kong point of view