How long can Hong Kong ride the IPO wave before it turns into the dotcom tsunami of 2000?

Analysts are unanimous in their view that today’s breed of tech companies will face the same upheavals that caused turmoil in the internet sector in 2000, where only the fittest survive

A record number of Chinese tech and internet companies are rushing to launch IPOs overseas this year, amid the looming shadow of overall tightening credit conditions, which bears a lot of similarities to the dotcom bubble and crash of 2000.

Just like what happened in the US nearly two decades ago, many of these IPOs are pushed by the need for cash amid intense funding pressure, as the cheap money era is coming to an end after the US Federal Reserve kicked off its rate-increase cycle and there is no sign of China ending its deleveraging campaign.

China tech IPO boom to continue for at least another year, says China Renaissance CEO

While it is getting increasingly harder to access onshore money from private equity funds, companies are turning to the public equity market for financing.

Some analysts said many tech start-ups are trying to catch the last train in the current cycle like what the Chinese internet portals did in 2000, as the issue of survival has become all the more important when winter finally comes. To grab the window of opportunity, many would rather risk a valuation cut and stock volatility.

If history is any guide, today’s breed of tech and internet companies could face a similar turnaround in fortunes and experience traumatic changes, leaving only the fittest to survive.

The great IPO rush

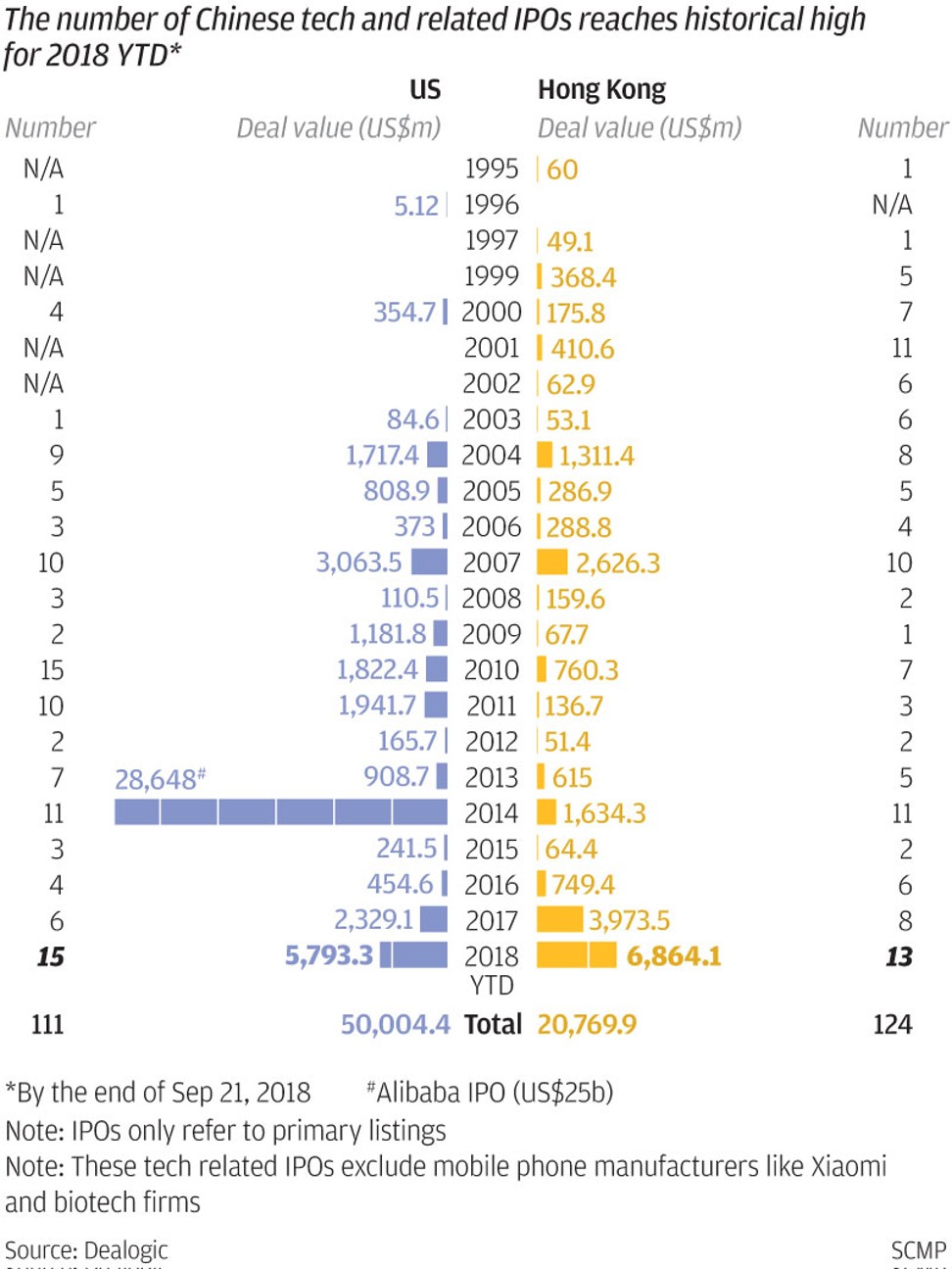

In Hong Kong, 13 Chinese tech and internet service-related IPOs launched this year, raising a combined US$6.86 billion as of September 21 – the highest on both counts since 1995, according to Dealogic data.

The data has not taken into account one of the largest flotations of the year – Xiaomi’s US$4.7 billion IPO, which Dealogic categorised as a smartphone maker.

The tech IPO wave is part of an overall listing boom. In the first eight months of this year, 150 companies listed on Hong Kong stock exchange, up 46 per cent year on year, based on data from the exchange.

This is in sharp contrast to the market sentiment that has changed significantly from earlier this year.

Since July, nearly 60 per cent of IPOs have fallen below their offer price on the first day of trading. The eight biggest tech IPOs in the past 12 months are all trading below their IPO prices. Yixin Group, China’s biggest online car retailer, has seen its shares plunge nearly 70 per cent from its offer price.

The Hang Seng Index recently entered a technical bear market, reaching a low of 26,613 earlier this month, down more than 20 per cent from a high of 33,484 on January 26. It has since risen, closing at 27,788.52 on Friday.

Even retail investors’ enthusiasm towards big listings has faded. Online food delivery service operator Meituan Dianping’s IPO earlier this month was barely subscribed by retail buyers, who placed only HK$2.6 billion (US$332.2 million) worth of orders. That is less than one per cent of the HK$370 billion capital that Ping An Good Doctor tied up in its IPO in May. It also pales in comparison with China Literature’s HK$520 billion lock-in retail capital last November.

Huge pipeline

But bankers said the IPO window in Hong Kong is still open and will probably stay open for another year.

“We expect a healthy IPO pipeline in Hong Kong over the next six to 12 months, despite macro-driven market volatility,” said Sunil Dhupelia, head of equity syndicate for Asia ex-Japan at Credit Suisse.

“Chinese companies, primarily in the TMT [telecommunication, media, and technology] sector, feature prominently in the pipeline.”

John Hall, co-head of investment banking for Asia-Pacific at JP Morgan, had similar views.

“There is still a robust IPO pipeline and the momentum is strong. Instead of postponing their IPO agenda, most issuers want to be prepared to catch the right market window. The recent volatility has made investors more selective but they remain tremendously enthusiastic for companies with a solid business model.”

Hong Kong regains crown from New York as the No 1 market for raising funds

Bao Fan, CEO and founder of China Renaissance, a leading home-grown investment bank advising on tech IPOs, said the window to list in Hong Kong is open, partly because of the new listing rules that took effect in April. The rules allow companies with dual-class share structure to list and also make it easier for biotech firms to launch their IPOs.

“2018 is a bumper year for IPOs. I believe next year will also be [the same],” he said.

Dennis Wu, CEO of Hong Kong-based Futu Securities, expected the current IPO boom to last till November and quieten a bit in December, before heating up again next year.

He added that Hong Kong is among the top IPO destinations in the world and is an open market with free capital flows. “As long as the issuers are good companies at reasonable valuations, you don’t need worry about the market’s holding capacity.”

Harvest time

Analysts said this unprecedented wave of IPOs has been fuelled by the rapid strides taken by Chinese tech firms in the past four to five years.

“In the past few years, many of these firms have made great progress supported by financing from private equity funds. They have matured and reached the IPO stage,” said Bao.

Lin Sha, an analyst at China Industrial Securities, said China’s mobile phone penetration rate had surged to 54 per cent in 2017 from 41 per cent in 2014, fuelling a rapid growth in the start-ups offering products or services related to the mobile internet.

Many of these start-ups have seen explosive growth, attracting enormous amounts of private capital amid hefty expectations about their valuations.

“This is similar to how many big internet portals rose in the early 2000s amid the internet revolution back then,” she wrote in a recent report.

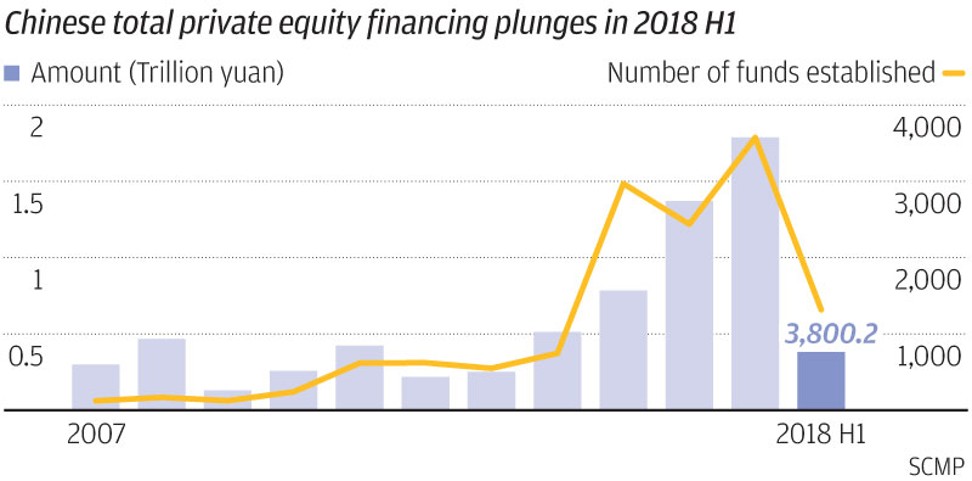

But this year, the Chinese private equity market, an important source of funds for start-ups, has tightened significantly.

For the first six months, money raised by private equity funds and venture capital firms plunged 56 per cent year on year on the back of China’s ongoing deleveraging efforts, weak domestic equity market, and a slowdown in economic growth complicated by the impact of the trade war with the US.

“It’s really hard to access onshore money from private equity funds now,” said Ashley Li, head of asset management at Ping An Securities. “Many LPs [limited partners] have no additional capital to invest [in PE funds], and some even want to cash in on their existing investments.”

Ronald Wan, chief executive at Hong Kong-based Partners Capital International, said a large number of PE funds set up in 2013 and 2014 have reached their harvesting phase.

A PE fund usually has an investment period of three to five years before it exits the portfolio companies. That has caused many PE funds to take the companies they back to go public.

Surviving winter

For the companies themselves, it becomes imperative to find other sources of funding when uncertainties are on the rise.

“Tech companies usually need constant blood transfusion in the early stages when they are yet to make a profit and need to keep burning money to support their expansion,” Wan said.

“When winter comes in the current capital market cycle, the most important thing is to survive.”

Kai Fang, managing director and head of equity capital market at China Renaissance, said it is better for issuers to grab the window of opportunity sooner rather than later given the uncertainties, as long as the company meets the requirements.

Where do blockbuster IPOs stand as the fizz goes out of Hong Kong’s stock trading debuts?

“We don’t know what will happen in the future. Maybe you can’t sell [the IPO] at the highest price now, but the top priority is to get it done. No one can predict whether it [the market] will become better in the future. So why not now?”

He said there are several motives behind a company’s desire to list.

“An IPO is so much more than just going public. It means a company can access more financing channels, boost its reputation and attract talent, and have a stronger bargaining position when talking to clients or even creditors.”

Bruce Wu, co-head of Citigroup’s Greater China equity capital markets group, agreed it is important to grab the window as long as it’s open.

“The volatility may cause issuers to recalibrate their timing, but they will persist with their plan.”

18 years ago

This unprecedented IPO wave has rekindled memories of what happened 18 years ago when the Nasdaq crashed after reaching a peak of 5,048 in March 2000.

Starting in June 1999, amid the dotcom boom, the US Federal Reserve raised its benchmark rate six times within one year, from 4.75 per cent to 6.5 per cent in May 2000.

Around that time, the US stock market embraced a concentrated IPO wave. 115 and 112 companies went public in 1999 and 2000 respectively, compared to the annual average of 72 between 1991 and 1996, according to data compiled by China Industrial Securities.

China’s four biggest internet portals at the time – China.com, Sina.com, NetEase and Sohu.com – also listed on the Nasdaq from July 1999 to July 2000.

However, the bursting of the dotcom bubble in March 2000 hit IPOs hard. Not only did NetEase and Sohu have to briefly postpone their listing plans and cut fundraising targets, but also saw their shares drop quickly as the Nasdaq plummeted.

The Nasdaq lost nearly 80 per cent of its value from its peak to a low of 1,114 in 2002, a period which many people call as the internet’s nuclear winter.

“Being able to list itself is a success,” Wang Zhidong, founder and then CEO of Sina, said in an interview with Beijing Youth Daily in 2000. “We caught the last train. The window was closing.”

Charles Zhang, CEO of Sohu, was then quoted as saying that it was not as if the company would have died had it not listed. “But the IPO significantly increased our chances of survival.”

Xiaomi’s value cut by almost half as smartphone maker prices IPO at the lower end of the price range

Eighteen years later, those comments resonate with Lei Jun, founder and CEO of Xiaomi.

“Being able to list is a huge success for Xiaomi, given the volatility on the capital market,” Lei said in an open letter in July.

Xiaomi raised US$4.7 billion in Hong Kong, the largest tech flotation of the year. But the fundraising value had to be cut by almost half from its initial target, as the company and banks became cautious amid a weak market and lacklustre investor interest. Its shares currently trade below its offer price, falling victim to worries over the outlook for Chinese tech firms and the US-China trade war.

Lessons from history

Many analysts agreed that what is going on now bears some resemblance to the past in terms of the funding environment for tech companies.

In the end, the great wave will wash away the weak, and only the fittest ones will survive

“Although it may not be as destructive as the bursting of the bubble back then, we shall be aware of a possible sharp turnaround in expectations for the new breed of tech and internet companies,” Wan from Partners Capital said.

“If a tech company mainly relies on burning cash to support its business without a viable business model, it easily dies when the environment becomes harsher.

The end of the dotcom boom saw about 210 US internet companies go bankrupt because of the broken capital chain, as it was hard to access financing, according to data from China Industrial Securities.

“When the bubble in the tech sector burst in the 2000s, many companies experienced a painful transformation, as their valuations were reassessed,” said Lin from the Chinese securities firm.

Those that survived bear three key characteristics: cautious investments, cost control, and how fast the company can monetise its traffic and achieve earnings, she added.

Bao from China Renaissance holds similar views, as he sees the ability to manage cash flows important to the survival of a tech company.

“In the end, the great wave will wash away the weak, and only the fittest ones will survive.”