Is Chinese capitalism in crisis, as stock market rout drives private companies into the state’s arms?

- China is sitting on a minefield of collateralised loans, with a third of the 4.5 trillion yuan of pledged shares almost at forced liquidation levels

-

The 33 per cent plunge in the Shenzhen Composite Index this year has wiped out 7.6 trillion yuan

China’s private enterprises, not even middle-aged in their experiment with capitalism, are rushing back into the government’s arms for financial succour, as the country’s worst stock market rout in three years has starved more and more companies of cash.

At least 32 companies listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen bourses sold controlling stakes to the Chinese state as of October 17, six of them to the central government, while 26 were taken over by provincial or city-level agencies, according to data by Shanghai Wind and China International Capital Corporation (CICC).

Call it privatisation in reverse, or re-nationalisation, as Chinese capitalism lays in crisis.

The 33 per cent plunge in the Shenzhen Composite Index this year has wiped out 7.6 trillion yuan (US$1.1 trillion) in value. That put the squeeze on companies that are already battling the aftermath of a trade war with the US, slower demand in the Chinese economy and tight monetary policy, forcing them to seek sanctuary in the coffers of the world’s second-largest economy.

Watch: US-China trade war – day 105 and counting

“This is about survival,” said Partners Capital International’s chief executive Ronald Wan. “When doors are shutting elsewhere, the only one who can save them seems to be the government.”

The root of the problem was in the access to capital. Chinese banks – most of them state owned and managed – preferred to lend money to state companies, with the public sector receiving 78 per cent of all loans in 2016, according to an estimate by Haitong Securities. Three years earlier, the ratio had been 60:40 in favour of the private sector, Haitong said.

That has pushed private enterprises to tap the capital market to raise funds through selling stocks or bonds. During the market’s bull run from 2014 to 2015, listed companies pledged their stocks for loans.

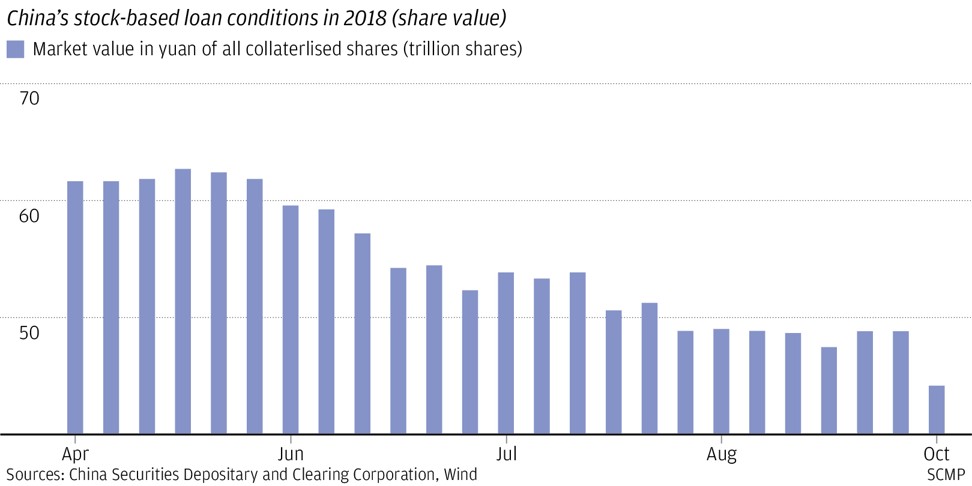

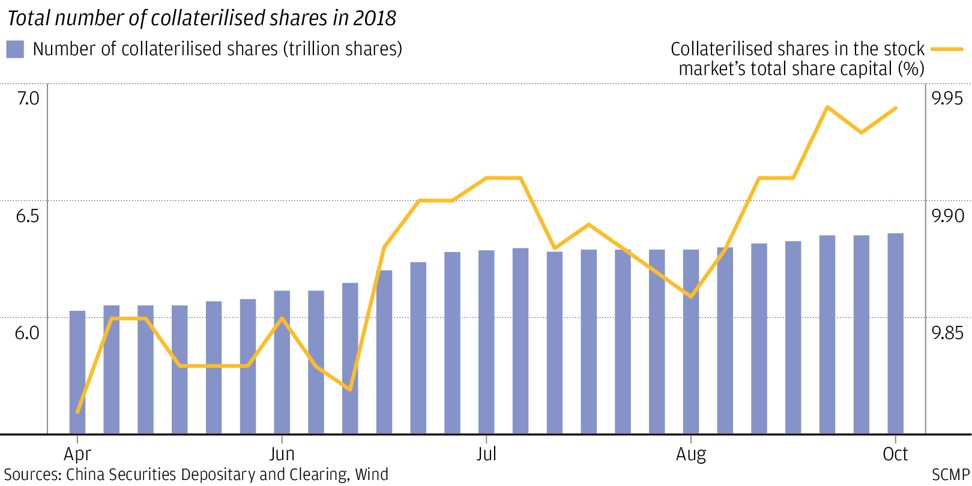

All but 13 of the 3,491 companies listed on China’s two stock exchanges have pledged their equities as collateral for bank loans, according to data by the China Securities Depository and Clearing Corporation, with the total value estimated at 4.5 trillion yuan, equivalent to the world’s 21st biggest economy and more than Hong Kong’s gross domestic product.

Shares trading on the smaller Shenzhen exchange have borne the brunt of the sell-off in China this year because the bourse is dominated by smaller companies, which tend to be more active in margin financing using their stock.

The benchmark index on the exchange, tracking 2,161 stocks, has underperformed the main gauge in Shanghai. A gauge tracking Shenzhen-listed small- and medium-sized companies has slumped 34 per cent, while the ChiNext index of start-ups fell 20 per cent.

Every index point drop in the stock market adds to the squeeze on borrowers. Their aggregate debt-to-asset ratio rose by 4.5 percentage points to 55.9 per cent at the end of August, from a year ago, government data showed.

The value of 35 per cent of China’s collateralised equities, estimated at 890 billion yuan, had fallen below their margin requirements as of October 12, while 61 per cent approached “cautionary levels” for margin calls, according to government data.

“It’s a vicious cycle: share drops lead to liquidation and liquidation leads to further share drops,” said Wang Zheng, chief investment officer at Jingxi Investment Management in Shanghai. “The recent declines, particularly among small-cap stocks, are being blamed for the problem arising from share pledges.”

To be sure, the Chinese government had seen the looming debt crisis, and began to forestall some of the cash crunch as early as last year.

The bank loans of several of the country’s biggest leveraged asset buyers – Anbang Group, CEFC Group, Dalian Wanda Group, HNA Group and Fosun Group – were put under regulatory scrutiny. Bank credit stopped, forcing all but one of them to turn from acquirers into asset sellers to cut debt and raise cash.

Watch: How the US-China trade war affects Hong Kong

The pace picked up in the past few months, spreading further and wider to more companies. At least 14 listed private companies have sold their controlling stakes to the government since September.

The government of Shenzhen, a metropolis of 12 million people near Hong Kong and the original test bed of China’s experiment with capitalism, has been a particularly active player in renationalisation.

The local authority earmarked at least 10 billion yuan to bail out listed private companies at risk of a liquidity crisis, with options to buy stakes directly, or through loans, according to various state media reports.

Since July, the city’s asset watchdog – the State-owned Asset Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) – has spent 2.2 billion yuan buying direct stakes in Shenzhen Infinova, Shenzhen Clou Electronic and Eternal Asia Supply Chain Management, all of which had pledged their stocks for loans.

Clou Electronic, whose controlling shareholder Rao Luhua pledged 99 per cent of his stake as collateral for loans, said it sought out the state bailout to “reduce risks of stock-based loans”.

The cash crunch was more dire at Shenzhen Yitoa Intelligent Control, a maker of devices for smart homes and connected appliances, which pledged its land holdings, office buildings and its chairman’s 26.6 per cent stake as collateral to banks. The company has 462 million yuan of debt due in April 2022.

“We expanded too quickly in the past three years through mergers and acquisitions,” Yitoa’s Chairman Hu Qingzhou said, according to a report by Securities Times. “The government’s prolonged financial tightening policy has caused difficulties for us and for private companies. We are strained for cash. We do not even have enough operating cash.”

An investment unit of the Shenzhen government took control of the majority of Yitoa on October 10.

Shenzhen wasn’t the only government to take over private businesses. Local authorities in Beijing, Shanghai and 14 provinces have bought stakes in listed entities from private entrepreneurs this year, Wind data showed.

Wuhu Token Science, a maker of thin film material for flat panel displays used by customers including Tesla, last week buckled under a 52 per cent share slump and sold a significant stake with voting rights to the state asset management unit of its home province Anhui.

“It’s good that the government is beginning to help,” said Jingxi’s Wang. “But you cannot expect every local government to do the same as Shenzhen. The best way to tackle the share-pledge crisis is that the decline on the stock market can be held in check. Given the current situation, however, this is not going to happen any time soon.”

It’s not just the equities market that is facing a stark winter. China’s fledgling bond market has also been riddled with defaults, with 29 issues missing payments on 67 corporate bonds in the first nine months, surpassing last year’s 44 defaults, Wind’s data showed.

Chinese Vice-Premier Liu He entered the fray on Friday, speaking in an interview with the Communist Party’s mouthpiece People’s Daily newspaper to calm nerves. The Chinese government is helping private companies get over their financial difficulties, extending the kind of financial aid that underscored the coexistence and cooperation between the public and private sectors, he said.

“It’s a good thing,” Liu said. “The state can divest, when businesses at the private companies improve.”

Liu wasn’t alone in trying to shore up market sentiment. The People’s Bank of China, as well as the country’s regulators in stocks, banking and insurance, all echoed Liu by drumming up financial support of smaller companies facing share pledge risks.

Commercial lenders will get more funding from the central bank to advance more loans to troubled companies, while insurers, brokerages and private-equity firms will be allowed to design special products to inject liquidity into the companies.

The bailout is not unlike the US Troubled Asset Relief Programme (TARP) signed into law during the George W. Bush administration, which spent US$475 billion to bail out Chrysler, General Motors and 16 other indebted US corporations.

In China’s case, the largest borrowers like Anbang and CEFC had to be nationalised as their debts carried diplomatic implications, said Kaiyuan Capital’s managing director Brock Silvers in Shanghai.

The takeover by the Chinese government “was done for practical and not ideological reasons,” he said. “Those companies were over-leveraged, headed for insolvency and likely to negatively impact investors, banks, domestic politics and foreign relations.”

Shifting the debt burden to the state may yet turn out to be a delaying tactic, as the government is now burdened with deteriorating assets and balance sheets.

China’s local governments may have accumulated 40 trillion yuan worth of hidden debts that are not reflected in official figures, creating a “debt iceberg with titanic credit risks,” S&P Global Ratings said this week in a report.

If all that off-the-books debt – mostly borrowed by local government financing vehicles, known as LGFVs – were included in China’s debt figures, the ratio of all government debt to GDP could have reached “an alarming level” of 60 per cent in 2017, S&P said.

The shrinking of China’s private sector had been written in official economic statistics since June 2017, when contributions to GDP was first surpassed by the state sector.

Profits growth in the private sector plunged by 27.9 per cent in the first seven months from last year, in stark contrast to the 28.5 per cent growth in aggregate earnings among state firms, according to an estimate by China Merchants Bank International (CMBI).

The private sector’s contribution had not recovered since, said CMBI’s chief economist Ding Anhua.

“Evidence shows that China’s private sector has been caught in a severe environment unprecedented in 40 years of capitalist economic reforms,” he said.

A recalibration of China’s ownership from private back to the state is more than mere academic curiosity, he said.

“The entrepreneurial vitality of the private sector has been essential to China’s growth in the past 40 years,” Ding said. “The relation between the government and the market, and the relation between state-owned economy and the private economy, are the two most controversial issues in the past 40 years about China’s social and economic development path. In each relation, the two are mutually exclusive in nature. We cannot have both. ”