We are acting in bad faith if we push small businesses into the world market without training and preparation

- Small-and-medium enterprises account for most of the businesses in Apec, and most jobs. They are the acorns from which tomorrow’s biggest companies grow

Putting aside the fight against protectionism, encouraging free and open trade, and getting economies to eschew one-on-one slug fests for multilateral solutions to trade problems, there is nothing more important in the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (Apec) forum than strengthening our small-and-medium enterprises (SMEs) and helping them to build business across borders.

SMEs - even though we define them messily - account for most of the businesses in all of our economies, and most of our jobs. They incubate many of our innovations. They are the acorns from which tomorrow’s biggest companies grow.

So when the Apec Business Advisory Council (ABAC) early this year tasked a research team from the University of Southern California’s Marshall School of Business to report how we could build their untapped potential, and attack the barriers SMEs face in building their businesses internationally,

we had confidence the findings were significant.

The team did not disappoint. Their research, reported to ABAC in Port Moresby earlier this month, found that the digital revolution, and the growth of multinationals’ global supply chains, had brought radical new cross-border opportunities for SMEs - in particular services companies that historically had few chances to grow their business internationally.

While the “normal” SME exporter of the past was an artisanal company that had picked up contact cards at a few trade fairs, the surging growth today is in companies using e-commerce platforms, or the subcontractors in multi-country supply chains for international trade (which account for 80 per cent of global trade), and in services providers that were spawned by multinationals that are contracting everything out to focus on “core competences.”

“Digital technology has reduced trade costs and expanded the reach of SMEs,” the researchers concluded. “It has increased the advantage of being small, specialised and being the best-of-breed. It has offered forward-thinking developing Apec economies ways to get out of the low-valued manufacturing sectors that they have traditionally been trapped in.”

The Marshall School researchers found that digital SMEs had twice the growth rate of non-digital companies. However, “inaccessible ICT (information and communications technology), lagging digital training programmes, cross-border data restrictions, resistance from financial institutions to alternative payment systems, and the controlling influence of global e-commerce platforms continue to be obstacles policymakers must address,” the report said.

The research team, which interviewed over 600 companies across the region over the past six months, also found a story of “frustration and continued disappointment” among SMEs.

“Trading regimes between economies remain a thicket of complex trade procedures and protectionist measures -effectively stopping SMEs in their tracks,” the researchers said.

They found little convergence between policymakers across the region on how to create a sustainable, supportive ecosystem for SMEs - which is shocking, given that SMEs account for around 97 per cent of companies across the region, and about half of the jobs.

Defining what counts as an SME - nowadays we fashionably call them MSMEs to highlight the importance of “micro” companies of 10 people or less - has always been tricky. In manufacturing, they normally need to employ less than 100 people. In services, less than 50.

For me, the crux of the definition is that they do not have specialised departments, such as IT (information technology), finance or marketing. The boss is a jack-of-all-trades that juggles all of these.

SMEs tend not to train. Rather they “buy” skills off the shelf, and offer little scope for career development, leaving staff to plan for their own pensions and long-term financial security, and take personal responsibility for their own skills development.

As our economies tend to rely increasingly heavily on SMEs and the “gig economy”, so governments need to support their capacity to plan, to improve governance, to get access to finance and new technology, to develop business networks, and track market developments.

They need to provide incubators and accelerators. They need to restructure education systems to provide lifetime opportunities to develop new skills - and to provide better-focused signals to working people who no longer have big companies to guide and provide their skills-development needs.

And as they encourage SMEs to venture into international markets, they need to ensure better access to knowledge about foreign markets, about trade costs, hassles at the border, non-tariff-barriers like licences and regulations beyond the border, and the explosion of risks that arise when companies venture into foreign markets.

Research by the University of Wellington in New Zealand has shown that over half of SMEs selling overseas do not have a formal contract, still less a dispute settlement clause to provide clarity in the event of a business dispute.

With European Union research showing 820 million worldwide business disputes in 2016 - each dispute taking about 15 months to resolve, and legal charges in multiple countries of at least US$1,000 an hour - it is no surprise that over a third of SME disputes go unresolved. at immeasurable cost to the

companies concerned.

As we in Apec encourage more SMEs to venture offshore, we are arguably acting in bad faith if we push companies out of the trenches into foreign markets, ignorant of the new challenges they face.

Much more needs to be invested in ensuring SMEs are “foreign market ready” before they venture overseas.

SMEs find it “particularly problematic” to manage customs procedures, widely varied local licensing, regulatory requirements and other compliance costs. The Marshall School team conclude that they need “greater transparency, simplified, plain-language rules, timely customs clearance, and they need multilateral trade rules, not bilateral Free Trade Agreements (FTAs).

“FTAs and RTAs (regional trade agreements) are negotiated from a large firm perspective, with little

consideration for the positive or negative impacts on MSMEs,” the team said. Most ignore the FTAs, and just pay the tariffs.

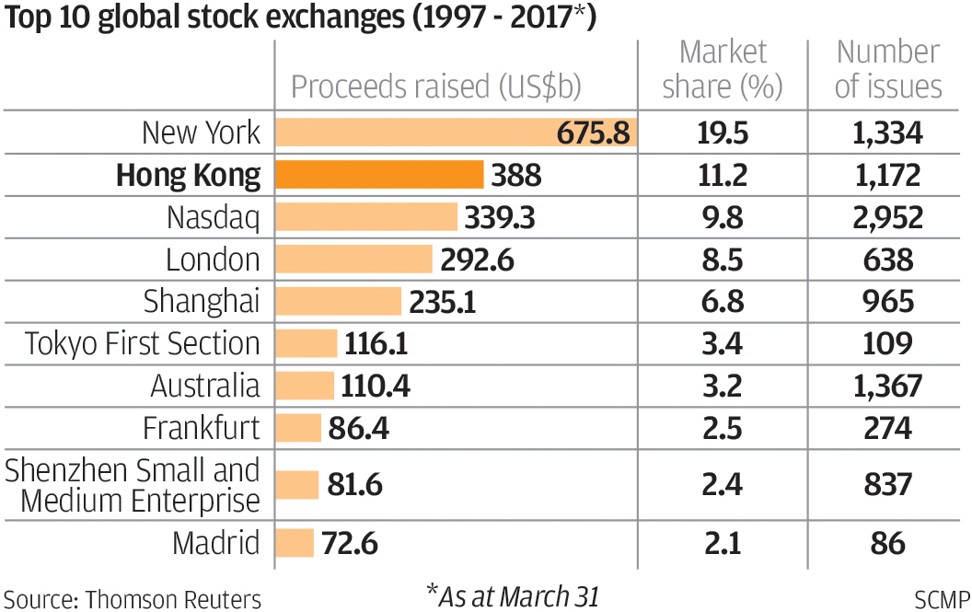

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Marshall School’s study puts Hong Kong and Singapore - traditional homes to “mini-multinationals” - out front in providing supportive environments to SMEs.

Australia, Canada, the US and New Zealand do well. Japan and South Korea would do better if they provided a better environment for women-led SMEs. As for Papua New Guinea, Russia, Indonesia and Vietnam, perhaps the less said the better.

Surprisingly, Chile also ranked highly - which augurs well as the country takes over Apec’s chairmanship in 2019. Perhaps they will provide the coherent leadership we need to fully develop the cross-border potential of SMEs.

David Dodwell researches and writes about global, regional and Hong Kong challenges from a Hong Kong point of view. He is also executive director of the Hong Kong-APEC Trade Policy Study Group