Dolce & Gabbana’s China faux pas shows global brands must tread gently on local sensitivities

- The destruction of D&G’s brand value in China is a lesson for foreign firms on marketing missteps, the power of social media, and crisis response in China

Dolce & Gabbana last week cancelled their Shanghai fashion show in the biggest overseas market for the Milan luxury designer, bowing to public backlash from a controversial advertisement and an Instagram post that offended Chinese consumers.

The two founders of their eponymous fashionwear designer apologised in a video post, five days after the fracas first erupted. It was the kind of publicity that no company needs, not least the kind of company whose very livelihood relies on public goodwill.

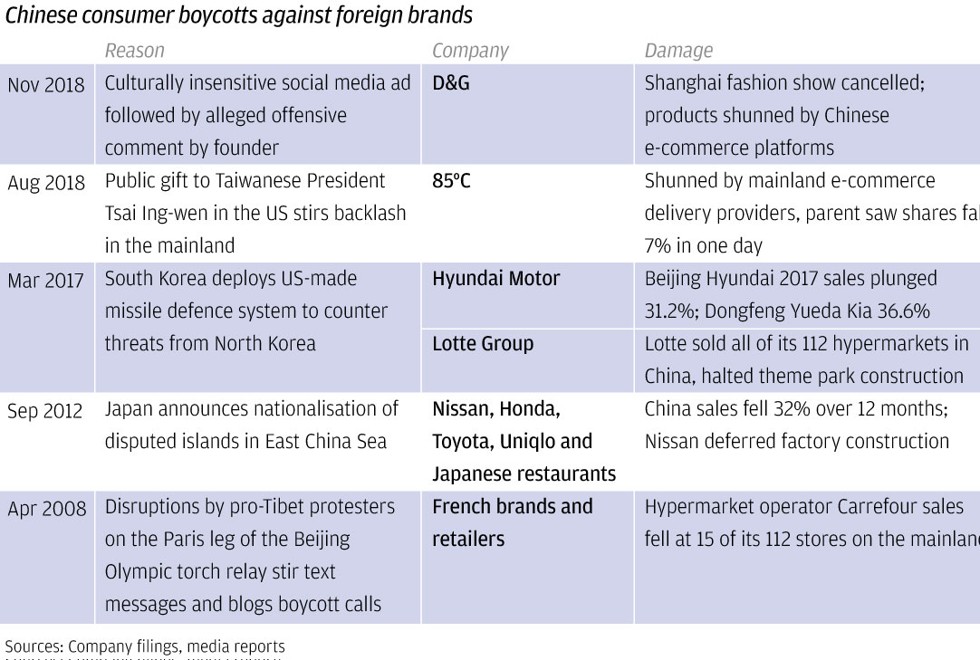

The Italian designer follows a dozen other brands from Japan, France, South Korea and Germany that have found themselves or their nations’ people being accused of offending the sensitivities of Chinese consumers. The way back from purgatory would require at least six months of public relations, shaving untold millions off revenues, according to retail analysts and consultants familiar with the power and history of China’s retail boycotts.

Chinese send clear message to D&G: insult our culture, pay the price

Foreign brands need to pay particular attention to the “thin-face and sensitive” nature of Chinese consumers, because they “are very sensitive to anything they would consider as a put-down,” especially with the perception that “China is regaining its historical and rightful place as a global superpower,” said Shaun Rein, founder and managing director of China Market Research Group, which helps foreign firms grow and invest in China. “There was a feeling that American and European nations looked down upon China,” so any impression of mocking the Chinese people or culture would give offence, he said.

Dolce & Gabbana’s troubles began on November 18 with a video advertising that showed a Chinese model struggling to eat pizza, spaghetti and a cannoli – a Sicilian dish of tube-shaped fried pastry filled with ricotta – to an Italian voice over. The video was deleted within 24 hours from the designer’s website after viewers posted criticisms on it.

How Chinese internet users roasted Dolce & Gabbana amid ‘racist’ ads fallout

While the advertisement was derided as tasteless by many, the real anger began after Stefano Gabbana’s Instagram chat with model Michele Tranovo was posted online, where the company’s co-founder included racist remarks in a rant against China for the backlash stirred by the advertisement.

Zhang said she wouldn’t attend the show, as did Li Bingbing, while some models reportedly refused to perform. As it became clear that one celebrity guest after another said they would not turn up at the Shanghai runway show on November 21, Dolce & Gabbana scrapped their event.

The fashion house is no stranger to risqué marketing campaigns, including a 2015 advertising that was banned from Italian publications because its imagery suggested a gang rape in progress.

The company is not alone in making cultural or political sensitivity blunders in China.

Three months ago, Taiwan’s Gourmet Master, which earns 62 per cent of its turnover from a chain of bakeries and cafes called 85°C on the mainland, caused offence after a report of its gifts to Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen during her visit to California.

Not just Dolce & Gabbana: five other brands that riled Chinese with fashion and beauty faux pas

Tsai’s political party has been accused of being pro-independence, a stance that offends China’s claim over the self-ruled island. Chinese consumers called for a boycott, causing Gourmet Master’s third-quarter sales to drop 9 per cent on the mainland, while overall profit plunged 41 per cent.

The Gap Inc, the San Francisco-based retailer of casual fashion, also found itself on the receiving end of Chinese consumers’ ire when it sold a T-shirt in May showing a map of China that omitted southern Tibet, Taiwan and the South China Sea, all territories claimed by China on officially sanctioned maps. The company withdrew the T-shirt and destroyed its stock.

Three months earlier in May, Mercedes-Benz ran a print advertising featuring one of its luxury sedans with a quote by the 14th Dalai Lama. The carmaker, which operates four ventures in China with Beijing Automotive Industry Holding (BAIC) and BYD, had to issue a “full apology” for quoting the Tibetan spiritual leader, who’s derided as a separatist threat by the Chinese government.

And the list goes on, underscoring how the marketeers who want to cash in on China’s burgeoning consumer market must take basic principles to heart, and let staff who are familiar with local sensitivities take part in the key message, analysts said.

More decisions are made centrally, [making it] difficult to keep the right level of sensitivity for local tastes and cultures

“More decisions are made centrally, [making it] difficult to keep the right level of sensitivity for local tastes and cultures,” said OC&C Strategy Consultants’ partner Pascal Martin. “Local management in each market is trained to obey global guidelines and decisions, therefore feeling less and less listened to. In the worst cases, it can affect the quality of the personnel that the brands end up hiring in local markets, often with weaker capacity to make judgment and decisions on what’s right or not culturally.”

Balancing the consistency of a global brand with the nuances and characteristics of local markets is a tough act, Martin said. The balance has swung too far in favour of consistency, because marketeers are under pressure by technology-shortened attention span to enhance the conformity of their communications, products, prices and designs, he said.

To be sure, Chinese consumers are not unique in showing nationalistic temperament. Americans have been known to use their spending power to boycott certain imports, like Chinese toys and pet food, citing quality and safety concerns, Rein said.

What sets China apart – besides the frequency of nationalist boycotts – is how foreign companies that are free of cultural faux pas have also been caught up in fracas between the authorities in Beijing with another government.

The French hypermarket Carrefour found itself the target of Chinese consumer boycotts in 2008 after supporters of Tibetan independence interrupted a relay of the Olympic torch through the streets of Paris. Carrefour’s sales fell at 15 of its 112 stores on the mainland. Still, the French luxury fashion brand Louis Vuitton appeared to have been spared the brunt of that boycott.

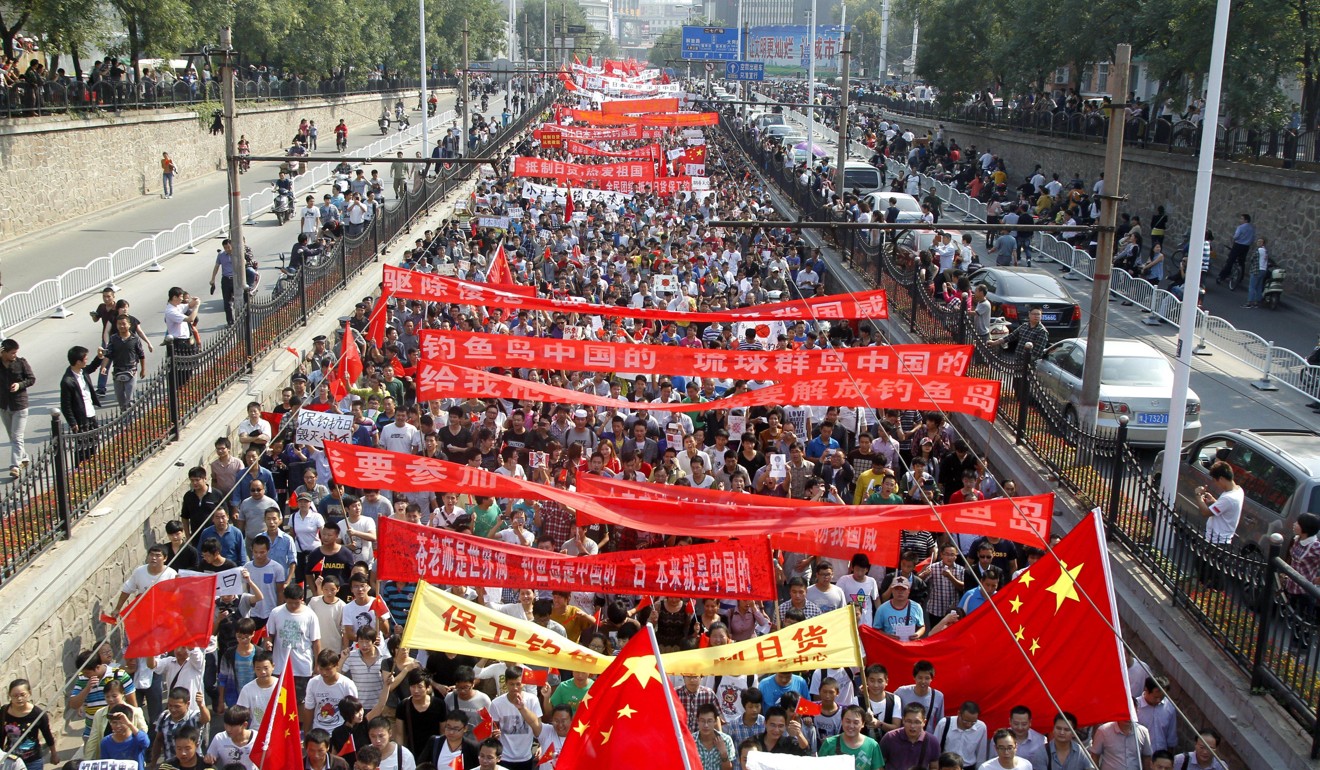

Fanned by a government-controlled media, China’s consumer backlash can sometimes turn violent. Protesters marched through the streets in a dozen cities including Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou in 2012 over the Japanese government’s plan to nationalise the Senkaku Islands. Located in the East China Sea, these uninhabited islands are known as Diaoyu Islands in China, and claimed by both mainland China and Taiwan.

Patrons were accosted and assaulted in Japanese restaurants in Shanghai, while cars made by Nissan, Honda and Toyota were overturned on some streets. Sales by these carmakers plunged for seven consecutive months, as owners were worried that their new purchases of Japanese marques would be targeted by vandals.

South Korea also felt the brunt, after the administration of then president Park Geun-hye agreed to deploy the THAAD anti-ballistic missile defence system against North Korean projectiles. Lotte, the South Korean chaebol that employs 60,000 people across 90 businesses – on whose land the THAAD systems would be deployed – was forced to sell its hypermarket operations in China after protracted consumer boycotts and penalties by the Chinese government.

Some industry watchers said Chinese companies had better watch out for missteps as it was only a matter of time before they get caught up in such controversies overseas as they globalise their operations.

So far, the most high profile globalisation challenge faced by a Chinese firm involves Huawei Technologies, which has been barred from providing 5G telecoms equipment to mobile operators in the US, Australia and New Zealand because of national security concerns.

“It is early days for Chinese companies in building global brands … they will also need to pay attention to cultural sensitivities as they enter new markets,” said St John Moore, partner and head of Beijing at Brunswick, an international business communication consultancy.

“The rapid destruction of D&G’s brand value in China will be a case study for [companies worldwide] for years to come on marketing missteps, the power of social media, and crisis response in China.”

China Market Research Group’s Rein said that as a big part of major brands’ marketing campaigns take place online, had D&G tested their advertisement and done market research on it, they would have realised very quickly that it’s just not acceptable in China.

Chinese e-commerce sites remove Dolce & Gabbana products after anti-China slur by company founder

Alina Ma, an associate director at research at market and consumer research firm Mintel, said that employees of foreign brands, whether local or foreign, tend to have “natural emotional ties” to the brands, which means they could sometimes fail to see potential misunderstanding of their communication messages by the wider local consumer public.

“Having another pair of eyes outside the organisation could be helpful,” she added.

But for Rein, D&G’s apology came way too late.