Hong Kong’s ban on e-cigarettes is absurd. If vaping is as bad as smoking, why hasn’t tobacco been outlawed?

Stephen Vines says the new ban is based on flawed arguments. Young people are also at risk from carbohydrates, trans fats and fast food, so is the Carrie Lam administration going to intervene in all these markets, too?

The ban is based on some seriously flawed arguments if indeed, as claimed, it has arisen from public health concerns.

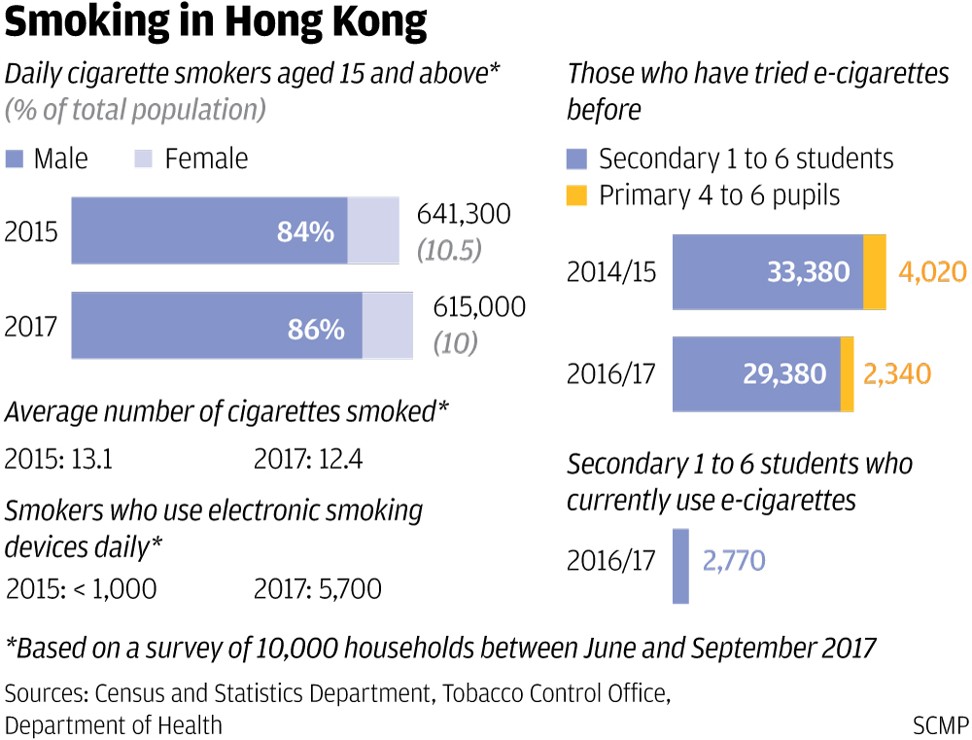

Those promoting the ban have overexcitedly argued that vaping either poses a greater health risk than tobacco consumption, or is just as bad. They have focused their concern on the attraction e-cigarettes hold for the young and cited controversial evidence that vaping does nothing to reduce tobacco consumption.

Highlights of 2018 policy address

Even if all these arguments are valid on health and social grounds – a bit of stretch, but let’s go with it for the moment – there is a fundamental illogicality here.

The answer is that these products have not been banned because their use is backed by the companies producing and selling them, and that this stuff is wildly popular with consumers. If there is a scintilla of doubt about this assertion, just pay a visit to your local McDonald’s, KFC or any other fast-food outlet that gives the health lobby the jitters.

Consumption of food and other products abounds with health risks, and governments who take their responsibilities seriously make efforts to alert the public to these risks. In the case of tobacco products, a mandatory labelling system spells out the health risks but, strangely, no such label is put on, say, a can of sugar-infused, fizzy drink with proven harmful effects.

However, the ban on e-cigarettes is in an entirely different category and undermines Hong Kong’s fundamental capitalist ethos that stresses choice, self-reliance and firm opposition to government control of markets. The validity of this ethos is most certainly open to debate but it would be far better if it came through the front door rather than the back door.

The slippery slope towards control of markets starts with bans on products that fall out of favour with government officials. If every product carrying a health risk were to be banned, businesses would enter an era of regulatory overreach and uncertainty.

In the case of e-cigarettes, the bulk of medical opinion supports the notion that they are considerably less harmful than cigarettes, which are not being banned.

Thus, an element of arbitrariness enters the equation – which, in a truly free market, is entirely unnecessary. Indeed, it could be argued that, while governments have every right to spell out health risks, consumers must be allowed to make their own judgments on these risks. Governments should respect the intelligence of the public and allow markets to work.

The road to hell, and unintended consequences, is paved with good intentions – and the ban on e-cigarettes may bear the best of intentions. In this instance, however, the consequences are entirely foreseeable.

Stephen Vines runs companies in the food sector and moonlights as a journalist and a broadcaster