Time to consider nature as well as nurture in Hong Kong’s education system

- Universities should take the lead in looking at student’s all-round achievements, not just their exam scores, when considering applicants

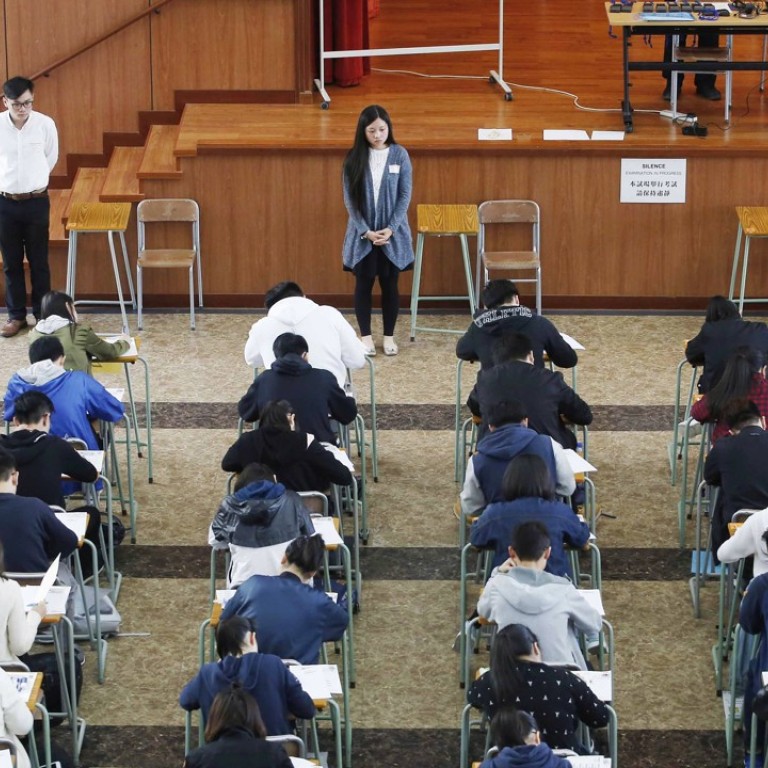

The recent debate about whether exams should be the sole determiner of local university entrance raises some interesting realities about the assessment of human abilities.

At a recent forum on education, former financial secretary Antony Leung Kam-chung suggested that our current university admissions system puts too much emphasis on the Diploma of Secondary Education (DSE) scores, while aspects of the “whole person,” such as a student’s non-academic experience, including talent in arts and sports, are largely ignored.

In response, Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor, who was attending the forum, said any consideration of non-academic factors could work against students from grass-roots families. Lam used her own experience as evidence to support the status quo of high-stakes summative assessment. Being strong at exams, Lam said she may not have been admitted into the University of Hong Kong, had such an exam-oriented system not existed when she was in secondary school. Certainly this is strong supporting evidence for her argument; however, cherry-picking one case close to home is hardly representative of the population as a whole.

The debate here is about whether the present “3322” system, under which students must attain Level 3 in Chinese and English language and Level 2 in Mathematics and Liberal Studies to be eligible for admission to local universities, continues to be appropriate in an age of increasing demands for inclusiveness. A closer look at this system reveals shortcomings that deserve attention.

For example, of the four core subjects, three display a distinct bias towards language skills; in other words, they are heavily tilted in favour of a student’s ability to effectively communicate. And while few would argue against communication skills being necessary in almost all areas of study and the workplace, one has to wonder whether this bias has shifted too far in one direction.

Lam rejects idea that life experience is more important than exam results

As a member of the academic community in the area of English-language education for several decades, I am amazed at how a few of my students can speak and write English with near nativelike ability without having set foot outside Hong Kong. At the same time, I also come across learners with similar backgrounds who are particularly poor at speaking and writing in English. Despite years of study, they continue to make the most basic errors and struggle to get their ideas across in English.

This difference in abilities cannot be completely explained by levels of effort or disparities in schooling experiences alone. While it is true that effort plays a big role in foreign language learning, it is clear to me that some students simply have a better aptitude for picking up languages than others. And the same goes for the ability to work with numbers. Most of us can remember maths whizzes from our school days, but also those who were hopeless with numbers.

The point of this discussion is that the present 3322 system is basically a grand leveller. It fails to effectively capitalise on these inborn proclivities harboured in all of us. And worse, it penalises those who have both inborn strengths and weaknesses among the core subjects. While I agree with our chief executive that the 3322 system is a reasonably fair way to sort students, many students with naturally occurring uneven aptitudes, such as being good at numbers but weak at language, get tossed by the wayside.

Happily, some universities have opened the door a crack to address this inequity. The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology now considers the applications of students who come up short in one of the four core subjects, but achieve Level 5 in the three others. Chinese University now considers students who attain at least Level 5 in three STEM subjects even if they did not make the grade in the other core subjects. This is a step in the right direction, but in an age that increasingly encourages inclusiveness, all our universities need to loosen the reins.

Paul Stapleton is an associate professor at the Education University of Hong Kong