How Google Translate may disrupt English classes, and every other subject, in Hong Kong schools

- Paul Stapleton says machine translation is advanced enough to produce believable versions of primary school students’ compositions. What are the implications for the way English and other subjects are now taught in Hong Kong?

We may be seeing the beginning of a technological disruption to our educational system, which could have far-reaching effects on the medium of instruction in our schools.

These challenges are pertinent to a study we recently completed in a Hong Kong school, using newly revamped technology that has the potential to play a key role in language education and curriculum guidelines because of cutting-edge neural network software coupled with brute-force computing power.

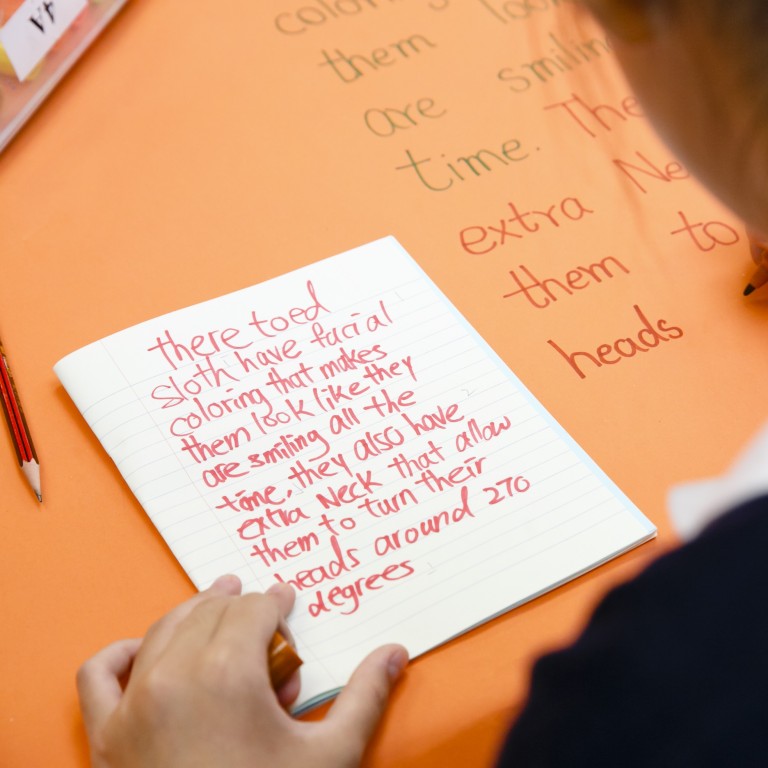

Noticing this advance, my colleague, Becky Leung, and I conducted a small-scale experiment in a Tai Po primary school. First, a class of students had to write a composition in English; a week later, they wrote on the same topic in Chinese. We then digitised all the students’ scripts and used Google Translate to convert the Chinese scripts into English. In the final step, using a bit of cheeky deception, we put the two sets of scripts together, randomly interspersed them, and asked English teachers from other schools to grade them for grammar, vocabulary and comprehensibility, without them knowing that half the scripts were products of machine translation.

The results revealed that the scripts originally written in Chinese and then translated into English by Google were graded a bit higher than those written in English. After revealing the design of the study during interviews with the dozen teachers – both native English speakers and locals – we found most had no idea that half the scripts were machine-translated. The upshot appears to be that Google Translate has reached a level of accuracy, at least for Chinese-to-English translations among Primary 6 students, that enables it to churn out reasonable finished products.

This could mean that, as machine translators continue to improve, local English language teachers may struggle to motivate some students who feel there is little need to learn the complex grammar and vocabulary of English when a computer can translate ideas written in their native tongue into fluent English at the tap of an app. A parallel with learning to read foreign languages is also easy to envision.

But this advance might not only affect language teachers and composition classes. The whole issue of the medium of instruction in Hong Kong, which has been debated for decades, could also be affected. Clearly, students learn better when they are taught in their native tongue, yet locally, a majority of Chinese students in secondary schools receive instruction in English in many of their subjects.

However, as technology for both written and oral translation is perfected, probably sooner rather than later, the dominant status of English in Hong Kong schools could decline. After all, what’s the point of teaching in a foreign language when perfect translations in both written and spoken form are instantly available on an app? In effect, online translation could act as a grand linguistic leveller.

Of course, this is all speculation. Technological disruption doesn’t always result in major change. However, we need to be aware that our youth are acutely tuned in to the latest technology that allows them to take short cuts to their goals. Educators should also stay tuned.

Paul Stapleton is an associate professor at the Education University of Hong Kong