North Korea is unlikely to give up its nuclear deterrent without a change in ‘hostile’ US policy

John Barry Kotch says Washington must consider concrete steps that would convince North Korea to denuclearise, such as gradual sanctions relief, removal of the UN Command or working towards diplomatic relations

While not quite a charade, it’s time to call a spade a spade. The president has remarked, “He wants to make a deal. I want to make a deal” and “if it takes two years, three years or five months, it doesn’t matter.” But it does matter and time is running out.

Washington appears out of step with its partners. To reach a workable consensus, it urgently needs to outline what a sanctions-relief scenario would look like

Nevertheless, there is a fundamental contradiction between inflicting pain on Pyongyang amid expectations that sooner or later it will “cry uncle” and encouraging it to comply using the step-by-step sanctions relief favoured by Russia – even as Moscow evades its responsibility by hosting North Korean labourers and clandestinely offloading refined petroleum products to North Korean ships on the high seas.

In short, Washington appears out of step with its partners. To reach a workable consensus, it urgently needs to outline what a sanctions-relief scenario would look like, in keeping with China’s call for parties “to make joint efforts to create a peninsula with peace, stability and complete denuclearisation”.

In sum, because the US possesses nuclear weapons, North Korea must also possess them until the US abandons its “hostile policy” based on a peace treaty or peace mechanism. Thus, North Korea cannot give up its “treasured sword” without a change in US policy.

Watch: Divided Korea – how did we get here?

Left out of this security equation, however, is the fact that that the nuclear deterrent exists primarily to defend Japan and deter the two other regional powers with significant nuclear capabilities – China and Russia – with North Korea late to the party.

North Korea seeks a security treaty with Washington paralleling that reached with South Korea at the end of the Korean war

However, putting the two Koreas on the same footing is sheer fantasy – the South has been a steadfast US ally for more than 40 years while the North has been an enemy state, a state sponsor of terror and, most recently, a nuclear outlier.

All of this cannot be wiped away in a single negotiation, or even a series of negotiations, but must be earned over time. In this regard, it took 40 years for South Korea to overcome decades of dictatorial and military rule and emerge as the vibrant, albeit imperfect, democracy it is today.

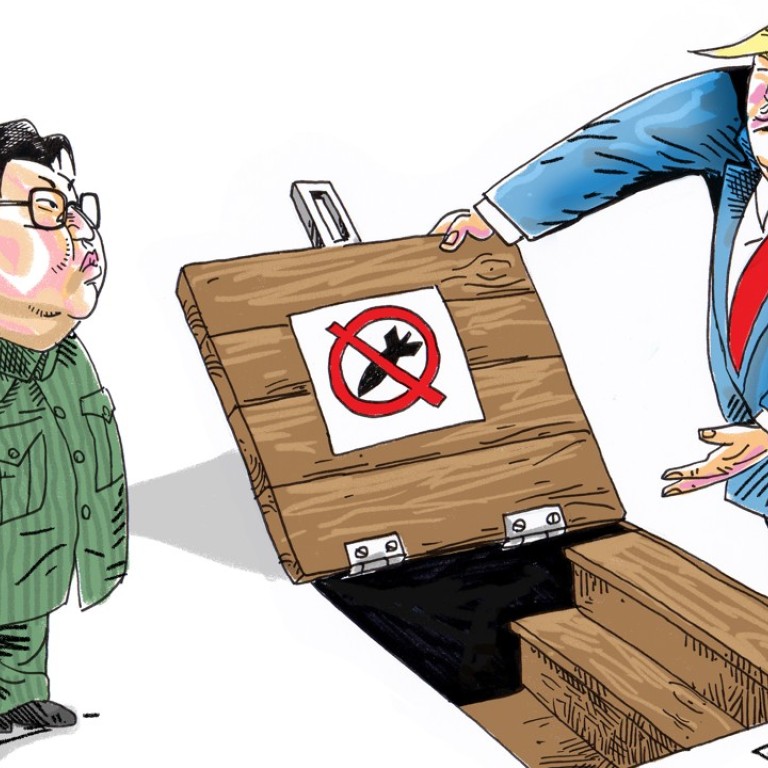

By the same token, unless Washington gets the logistics right, Pyongyang will never comply. The notion that it’s up to the North to “walk through the door [Trump’s] holding open”, in the words of National Security Adviser John Bolton, is ludicrous without some “give” on the US side, evidenced by a changed relationship.

Without this, Pyongyang is understandably loath to give up its nuclear deterrent.

That was the goal of the earlier 1994 US-North Korean Agreed Framework that followed former US president Jimmy Carter’s successful mediation with then-North Korean leader Kim Il-sung, which eliminated the reprocessing of spent plutonium at the North’s Yongbyon nuclear reactor and paved the way for light-water reactors by the Korean peninsula Energy Development Organisation consortium to produce electricity.

However, the agreement, which also provided for liaison offices in each other’s capitals, as well North-South dialogue that could eventually lead to full diplomatic relations, was abandoned by the George W. Bush administration.

Flying in and out of Pyongyang and conducting negotiations in Vienna is no substitute for a permanent venue in each other’s capitals in dealing with the complexities of denuclearisation.

At present, a train wreck looms with the two Koreas unable to implement new economic agreements, while Washington and Pyongyang tread water over denuclearisation.

John Barry Kotch is a political historian and former State Department consultant