Why Xi Jinping should learn from Chiang Kai-shek, instead of modelling himself on Mao

- Chi Wang says Xi is said to emulate Mao but he ought to focus not only on the communist victory but also on Chiang Kai-shek’s missteps during the civil war

- Seventy years after the communists took Manchuria, the dangers of hubris and prioritising one’s personal power over the needs of the people are evident

In 1948, China’s civil war reached a major turning point in favour of the communists. What is emphasised more in China, however, is Mao Zedong addressing a crowd in Tiananmen Square on October 1, 1949. As someone who lived through both the Japanese occupation and the Chinese civil war, I feel compelled to shed light on this period and why understanding the truth about Mao’s victory over the nationalists is more important today than ever before.

Watch: ‘Xi Jinping Thought’ enshrined in the party charter

As those who were alive in 1949 die, the truth will become harder to discover. My family had just spent years trying to escape Japanese troops before ultimately ending up in Japanese occupied territory. When victory over Japan was announced, they hoped China would finally find peace. But war quickly resumed – this time with Chinese killing Chinese.

While China’s narrative focuses on the communist victory, just as important is how Chiang Kai-shek and the nationalists lost the war

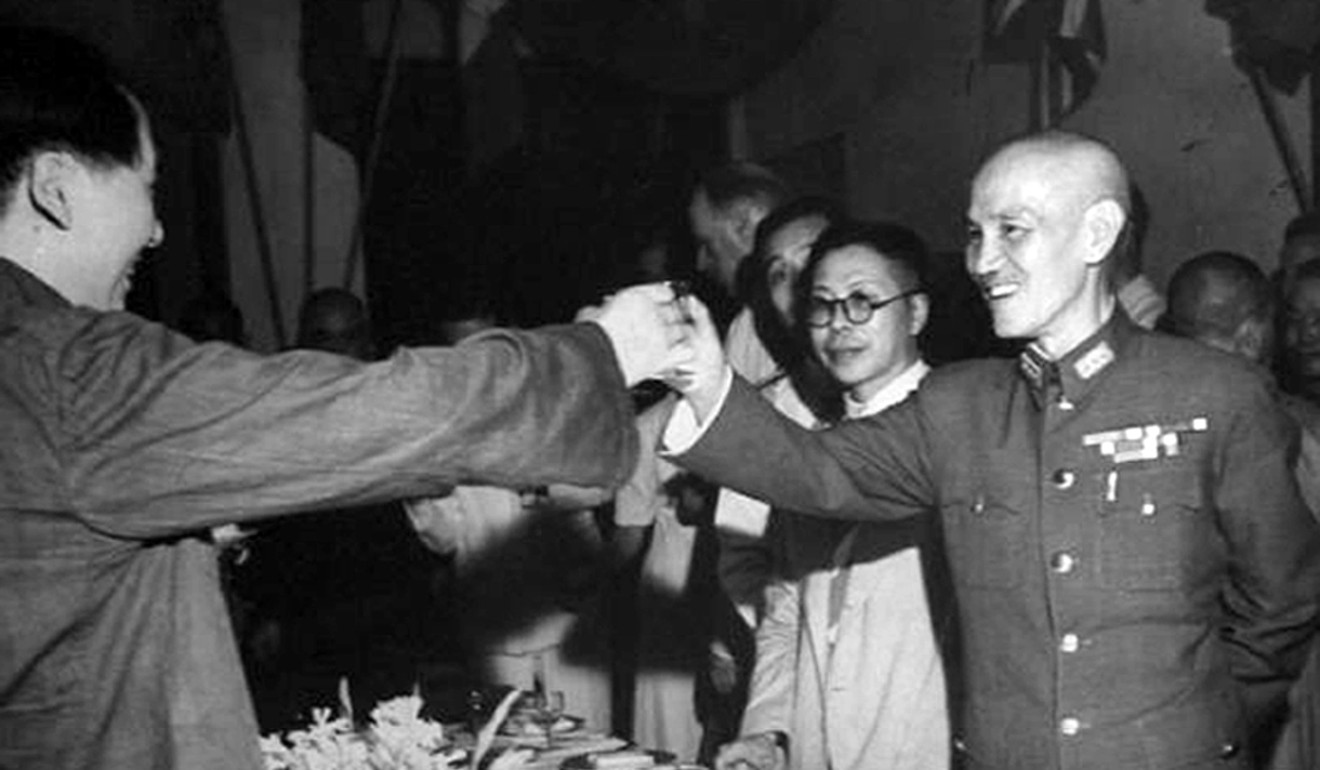

Many were disillusioned with Chiang Kai-shek’s government. Mao ran a successful propaganda campaign vilifying Chiang and painting a picture of a better China. Meanwhile, the Republic of China faced hyperinflation.

As cities changed hands, little regard was given by either side to the fate of civilians, with countless killed or left as refugees.

In 1948, Manchuria fell to the communists. Manchuria – comprising the northeastern provinces of Liaoning, Jilin and Heilongjiang – was the main battleground of the civil war. The siege of Changchun left upwards of 160,000 civilians dead and the city in communist hands by October.

Then, the last major battle took place in Shenyang. My cousin, Lieutenant-General Zhou Fucheng, who commanded the Nationalist Army there, was captured and forced to surrender. By then, many nationalist troops had already defected to the communists.

While China’s narrative focuses on the communist victory, just as important is how Chiang and the nationalists lost the war. The communists would never have gained such inroads into Manchuria if Chiang had not given up on the region in the first place.

Shenyang was seized by the Japanese in 1931 after the explosion on the Japanese-controlled railway, known as the Mukden Incident. Soon after, a Japanese puppet regime controlled all of Manchuria. Chiang’s priority, however, was beating the communists.

After the Japanese were defeated, Chiang considered sending the Young Marshal and my father, General Wang Shuchang, also from Manchuria, to secure the region. Worried Manchuria might separate from the Republic of China under strong leadership, Chiang instead restructured the region and sent southern officials who were distrusted by the locals. This kept Manchuria disorganised and weak, giving the communists, with the help of the Soviet Union, a greater ability to gain control of the region. Zhang Xueliang was placed under house arrest and never returned to his beloved Manchuria.

From these facts, we can see some important truths. The civil war did not begin with victory. Years of struggle and conflict came first. Even after the war, Mao’s promises of a better China only led to the Cultural Revolution. Will Xi’s promises of a “Chinese dream” also lead to disaster? By ignoring the scars of the past, China’s leaders will be less likely to show caution in the future.

Second, is that the civil war was not won by Mao – or even the communists – alone. Zhang’s actions and Chiang’s mistakes played pivotal roles. While Xi is a strong leader with a vision for China, he needs to remember that things outside his control also play an important role. Mao was not an all-powerful god; Xi cannot expect to be one either.

Along these lines, Chiang’s fall also shows the dangers of hubris and putting one’s personal power first. Chiang’s fear of losing control over China led him to ignore advice, alienate potential allies and disregard the needs of his people.

As a result, he actually weakened his position and pushed many towards the communists. These are important lessons for Xi, a leader amassing his own personal power and working to maintain it.

Chi Wang, a former head of the Chinese section of the US Library of Congress and former university librarian at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, is president of the US-China Policy Foundation