Free market can’t save us from climate change – the likes of China, not the US, can lead the effort though

- Andrew Sheng says the world has bigger problems than trade or national security threats. Instead of spending on defence against each other or leaving it to the free market, countries should step up and deal with climate change

The remarkable difference in priority given to defence and climate change is evident from a few figures. According to one study, in the 21 years from 1993 to 2014, total US expenditure on climate change came to about US$166 billion, in 2012 dollars. This is a mere fraction of the US$590 billion the US spent on defence last year.

But wait a minute. Since 2014, even the US Department of Defence has recognised that climate change is a “threat multiplier”, meaning that hurricanes, droughts, floods and crop failures exacerbate conditions like poverty and political instability, which might be a recipe for conflict. Europe’s migrant crisis is the result of failed states in the Middle East and North Africa, war, and also climate change.

Because climate change is global, failure to address its causes will do great harm. So here is the real choice: do we spend more on defence against human enemies, or do we work together to deal with climate change that is becoming inevitable and will harm us all?

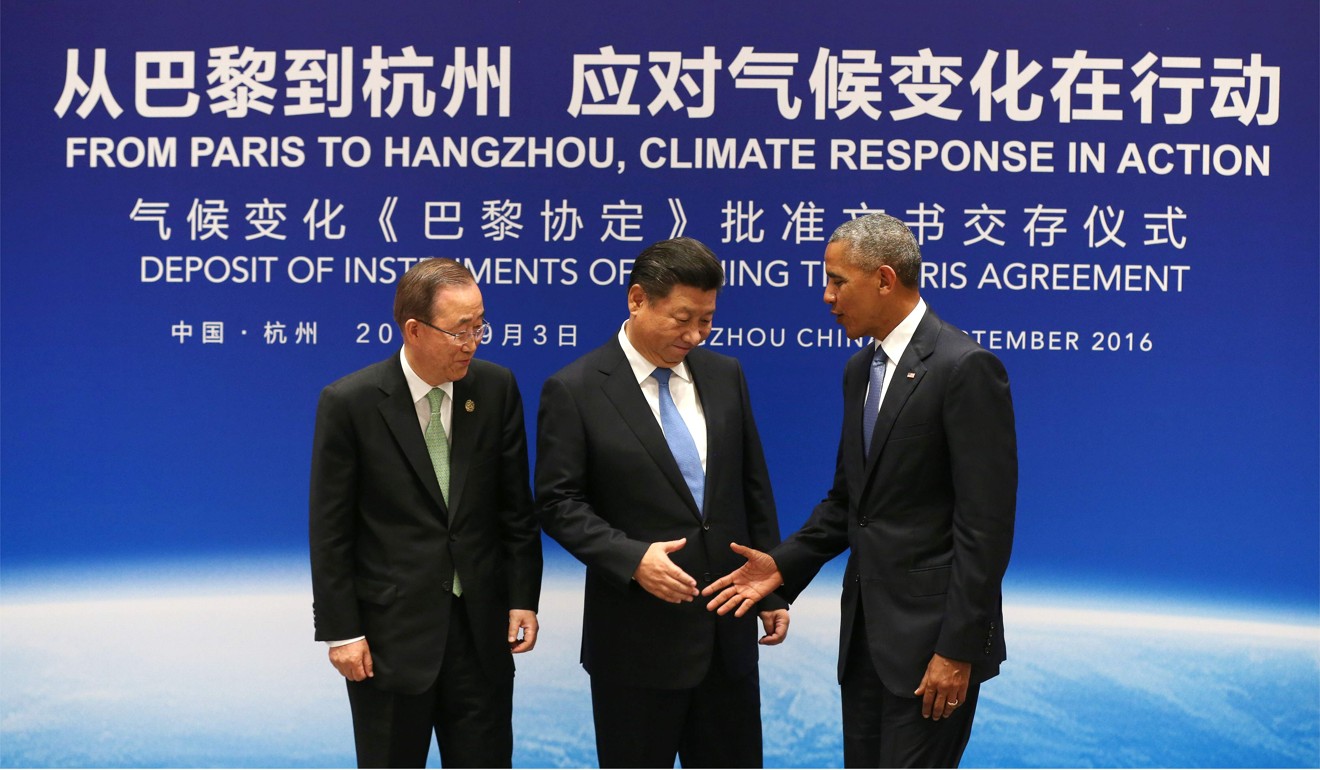

If we ignore climate change and work on arms escalation, then the outcome will be more disastrous that anyone can expect. However, if nations work together on climate change but one party gets stronger at the end of the day, won’t that be a disaster for the other nation? To put it another way: in a dilemma between cooperation and competition, can geopolitical rivals trust each other?

The divide between China and the US is whether the state or the market should drive development. In East Asia, be it Japan or China, the state is in the driving seat. The US believes that the market should lead, though there has been increasingly complex market regulation since the 2008 financial crisis.

Can the invisible hand of the market deal with the visible threat of climate change? Ten years ago, it was understandable that climate change was not high on the political agenda. But the world has had a few of the hottest years in history since 2015, and there can be little doubt something needs to be done to avert disaster.

In his new book, The Sustainable State, think tank founder Chandran Nair argues that the state, democratic or otherwise, may be the only institution capable of leading an effort to deal with climate change.

Technology alone can’t save the day; it is useful for improving energy efficiency, but it cannot be used effectively without the state making regulatory and other changes. Nor can the private sector be counted on to deal with climate change alone. Businesses, driven by profit, have too many excuses not to change climate-unfriendly practices.

As Nair rightly notes, the state, promoting the greatest good for citizens, has a better chance of addressing climate change at a national or global level.

After all, the market, an aggregation of individual choices and decisions, might not always provide the best, or wisest, solution. Just look at the examples of the Brexit vote and the rise of right-wing populist politics in Europe. In the rush to blame foreigners and immigrants for national problems, it is easy to overlook bigger problems like global warming.

But finger-pointing, or waging a trade war, is about as productive as fighting over deckchairs on the Titanic.

However, if we accept that climate change is the real enemy, doing something about it together makes more sense than fighting against each other. Then again, as Walt Kelly’s cartoon character Pogo, surrounded by garbage in a forest, says, “We have met the enemy and he is us.”

Andrew Sheng writes on global issues from an Asian perspective