All You Can Ever Know review – Asian-American adoptee’s search for birth parents is a tango of abandonment, embrace

Nicole Chung grew up in a white, Catholic family in the Pacific northwest. Her memoir wrestles with biology and culture as she searches for her birth parents

All You Can Ever Know

by Nicole Chung

Catapult

4/5 stars

As a child growing up in the US, Nicole Chung rummaged through the wooden box that sat high on a shelf in her parents’ room with thoughts of burying it in the backyard for a treasure hunt. This is a memory she recounts in All That You Can Ever Know, a tender, unsentimental memoir of her adoption and the search for her Korean birth parents.

Debut novel a largely realistic tale of Chinese ‘second wife’ and immigrant

She returned to that box of family photos and vital papers with fresh purpose as a teen. While the legal-size envelope she found there had held scant interest for a playful child, it offered unnerving possibilities for the bright, inwardly discontented adolescent Chung was becoming.

The envelope was “buried among the photographs, stamped with a Seattle address”, she writes. “Inside was a bill for US$500 and a business card” with the name of the lawyer who had handled her adoption. When she dialled the lawyer’s office, her “heart was racing,” she writes. “By now I felt less like a detective, more like a criminal. Should I just hang up?”

All You Can Ever Know has the patient pacing of a mystery and the philosophical heft of a sceptic’s undertaking. Along the way, Chung wrestles with biology and culture, heritage and belonging, race and motherhood – always from an intensely personal vantage. The apex of her search coincides with Chung’s first pregnancy, providing even more material for the memoir’s tango of abandonment and embrace.

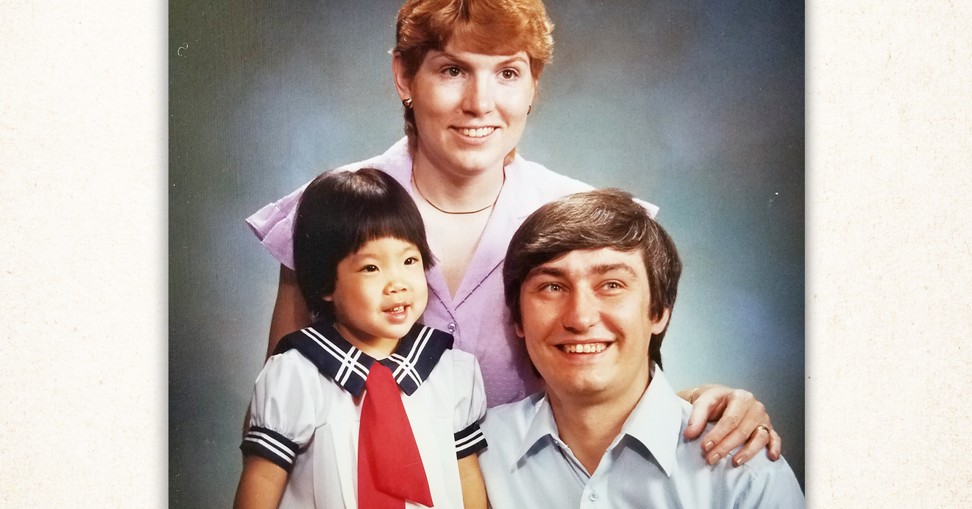

In recent years, adoption agencies have offered new strategies to help adoptive parents nurture children when they are of a different race and cultural background. But in 1983, Chung’s parents – a nice, white Catholic couple who left Ohio for the Pacific northwest – employed a sort of “colour-blind” approach. Intended to make sure their only child knew she belonged, their strategy left Chung alone with questions of race and her place in a family that looked nothing like her.

“My parents and I had certainly never discussed the possibility that I might encounter bigots within my school, our neighbourhood, our family, in places they believed were safe for me,” she writes. And so, the first time a child taunted her about being “Chinese” and adopted, she was doubly wounded. “This felt like a different kind of humiliation, one I could not expect to understand,” Chung writes.

“They had always insisted the fact that I was Korean didn’t matter; what mattered was ‘the kind of person’ I was. How could I tell them they were wrong?”

Chinese birth tourism: pregnant women in California’s ‘maternity hotels’ given voice in empowering novel

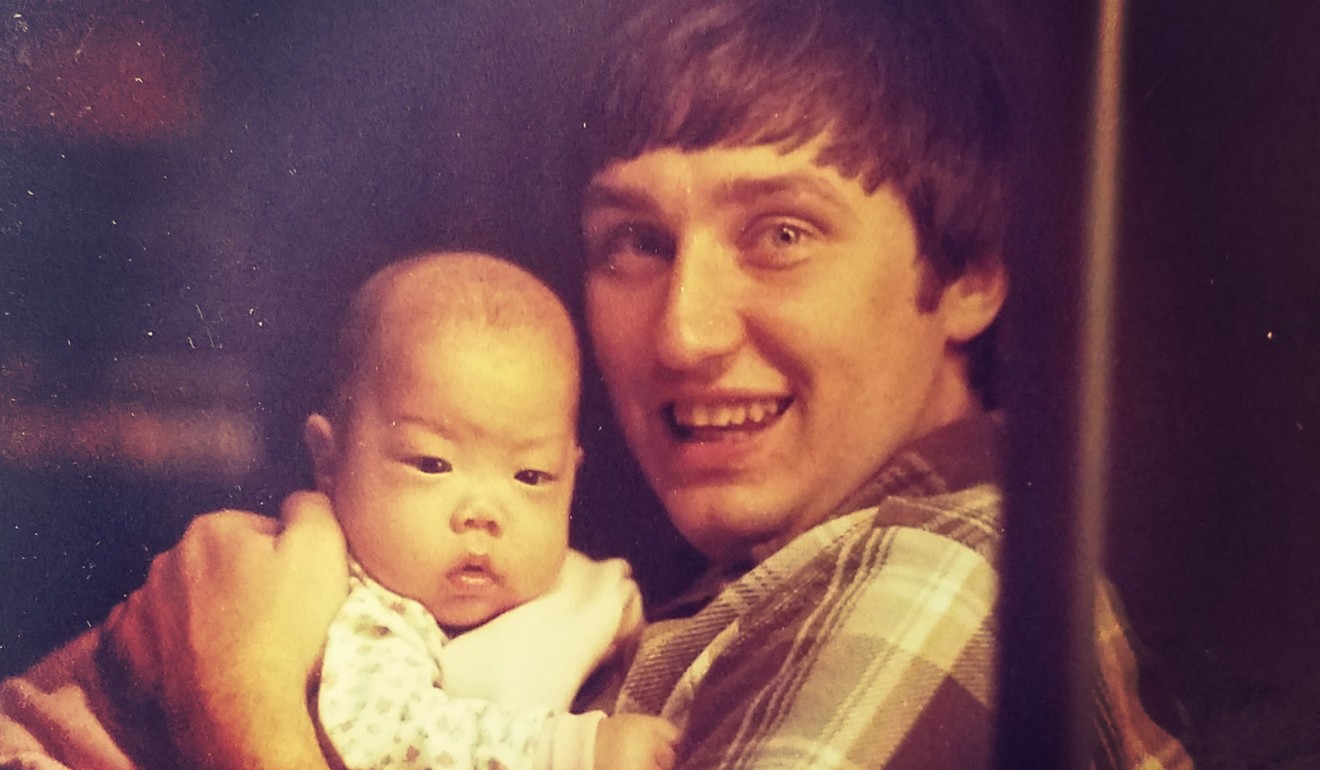

And hadn’t she been told that her birth parents – hardworking immigrants with a small business in Seattle – wanted her but couldn’t keep her? Hadn’t they made the selfless decision to put her up for adoption for medical reasons? Chung had been born 10 weeks before term. Her prognosis was iffy and she spent weeks in the neonatal intensive care unit before her grateful new parents “tore their baby out of the arms of a hospital nurse”.

The memoir’s title is a nod to Chung having been told that the scant information she had about her biological family would have to suffice. The adoption had been closed, and throughout the memoir her parents appear loving if unhelpful, even obstructive (especially her mother).

Early on, Chung begins weaving a new character into the tale: her birth sister. It’s an unexpected turn, one that subtly confirms that Chung’s search will be successful even as it adds a layer of intrigue to that saga. Telling her birth sister’s story the way a novelist or, as she is here, a biographer, might is Chung’s finest decision. These interludes provide illuminating pauses (and significant doses of fact — about her parents’ divorce, her mother’s violence) to her own tenacious first-person grappling with loss and family.

“I searched because I wasn’t content with what I’d always known,” writes the mother of two daughters and now younger sister of a woman she found searching for parents who were not quite what she imagined. “Reunion has taught me that there is no way to remake your history or your family in the image you want,” Chung admits. “But there can be more, if you are willing to look for those stories that were lost — you might find someone new to forgive, to love, to grow with.”