Review | Hong Kong Noir: 14 short stories delve into ghosts and spirits lurking in ultra-modern city

- The ‘umbrella movement’ protests, Japanese occupation, the post-war boom, and the 1997 handover to Chinese rule are among the backdrops to the stories

- The book is part of an international series, and its editors say working in Hong Kong they ‘constantly feel like kids in a confectionery shop’

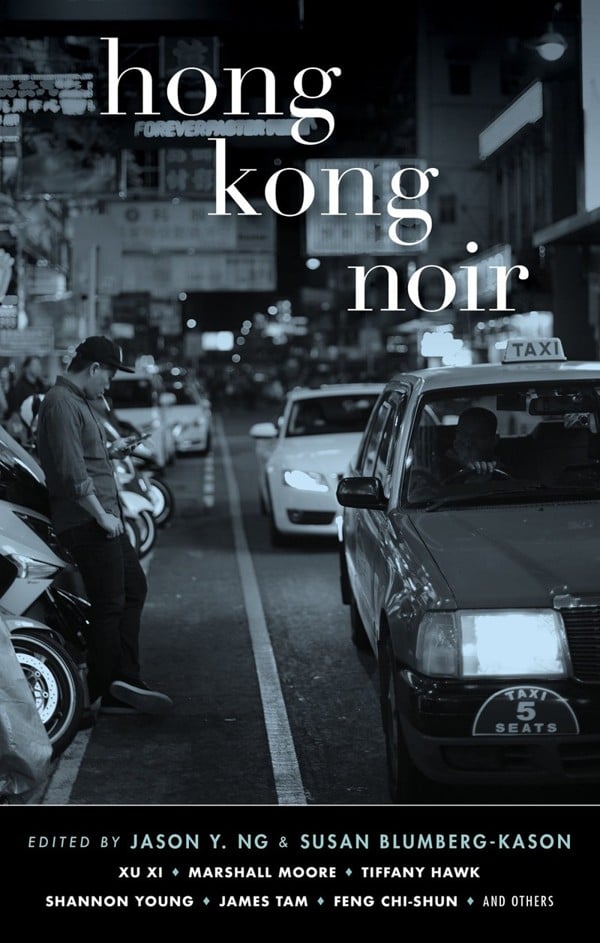

Hong Kong Noir, by various authors, edited by Jason Y. Ng and Susan Blumberg-Kason, Blacksmith Books/Akashic Books

Hong Kong may be known for its cold-hearted capitalism and ultra-modern efficiency, but it is also a society steeped in tradition and superstitions. Fortune-tellers hold sway over tycoons, property giants avoid having an unlucky fourth floor in buildings, and shrines shrouded in incense smoke sit among the world’s most expensive real estate.

Book review: Another Hong Kong, edited by various

Hong Kong Noir digs below the financial centre’s gleaming surface to unearth stories of the city’s ghosts and spirits. “There is a bounty of quirks to make writers like us constantly feel like kids in a confectionery shop,” the book’s editors say in the introduction.

The “Noir” short story series, launched in New York in 2004, features a different international city in each edition. Hong Kong is the chosen locale for 14 stories – an inauspicious figure which, as the editors note, sounds like “certain death” in Cantonese. The 14 authors were only instructed to end each tale “on a dark note”.

The stories touch on major points in Hong Kong modern history: the horrors of Japanese occupation, post-war poverty, the economic boom under the British, the city’s return to Chinese sovereignty, and the tensions of the 2014 “umbrella movement” occupation of key thoroughfares by pro-democracy activists. What better way to tie together the present and the past – the living and the dead – than through ghost stories?

One good example is The Kamikaze Caves by Brittani Sonnenberg, about a modern-day woman who envisions the ghost of a frightened young Japanese soldier, whose soul is trapped in a Lamma Island cave.

Xu Xi, Hong Kong’s best-known contemporary writer internationally, looks behind the glitz of the city’s golden era as it was depicted in Hollywood films such as The World of Suzie Wong. In her new story TST, Xu Xi gives voice to long departed and long abused bar girls.

“We can go to TST [Tsim Sha Tsui district] because of that wealth and the men who haunted the district, trolling for love, gluttonous with desire,” these women lament, decades after they have been forgotten by their families and lovers. “After all, we were young and pretty enough, smart and hungry enough, sad and desperate enough.”

Rich poor gap in Hong Kong the theme of new short stories collection

Another authentic Hong Kong voice is Feng Chi-shun, a retired doctor whose earlier works document his own working-class Hong Kong childhood. (Coincidentally, one of Feng’s earlier books was also titled Hong Kong Noir”) In Expensive Tissue Paper, he describes the ironically named Diamond Hill, a 1950s squatter village for new migrants from China, with “sleaze oozing from brothels, opium dens, and underground gambling houses”.

The tensions and paranoia of the 1960s come to life in Shen Jian’s Kam Tin Red, about a boy caught up in a murder during the leftist riots.

In Ticket Home by Charles Philipp Martin, another young man is embroiled in a cops-and-robbers romp, back when the British Hong Kong Police Force still patrolled the city.

Both stories set during the 1997 return of Hong Kong from British to Chinese rule are, rather fittingly, about the break-up of partnerships. One Marriage, Two People by Rhiannon Jenkins Tsang – an allusion to the “one country, two systems” arrangement for governing post-handover Hong Kong – explores the cultural chasm between a couple.

You Deserve More by Tiffany Hawk is about a middle-aged woman’s sneaky flirtation with an old flame in Lan Kwai Fong, and the fate that befalls her and her ex.

A View to Die For by Christina Liang is another love story with a shocker ending.

Some of the stories in Hong Kong Noir are downright gory. Phoenix Moon by James Tam would not be out of place in a tabloid or horror film. The romantic-sounding title refers to the working name of a hooker who seeks revenge on a corrupt police officer – with an extra-sharp pair of shearing scissors.

Blood on the Steps by Shannon Young is set on Pottinger Street, where vendors ply their Halloween decorations until something truly grotesque happens.

There are a few stand-out stories, such as The Quintessence of Dust, about a family business related to the suicides on Cheung Chau. Author Marshall Moore is a vivid storyteller who evokes the feelings of despair as stressed-out teenagers take their own lives on the small island.

Another tragic tale about Hong Kong youth is Carmen Suen’s Fourteen, about a girl living in one of the thousands of 300 sq ft flats in the Wah Fu public housing estate.

Book review: Hong Kong Gothic, anthology

Hong Kong Noir opens with a modern-day story, Ghost of Yulan Past, by Jason Ng. An idealistic University of Hong Kong student and an enticing young woman at her family temple meet during the Hungry Ghost Festival, and chat about current issues such as the Umbrella Movement.

Twenty years into the handover, the Sword of Damocles that hangs over the city’s heads is inching ever closer

It is not my favourite story by Ng, but he deserves credit for editing and writing in what seems like every recent Hong Kong anthology. (His short fiction also appeared in the recent Hong Kong Highs and Lows).

The editors of Hong Kong Noir save the best for last. The book finishes with Ysabelle Cheung’s quietly sinister Big Hotel, the nickname for the city’s main funeral home. It is a subtle piece of writing about two disillusioned youth trapped in their families’ morbid businesses – the girl makes floral wreaths for burials, while the boy closes up the funeral home at night.

There is a method to the madness behind Hong Kong Noir. As Ng and co-editor Susan Blumberg-Kason explain, the purpose of this anthology is to “write about our beloved city and work our hardest to preserve it in words” – to capture a slice of Hong Kong life before it disappears, and bring those stories to a more global audience.

After all, what is most frightening are not made-up ghost stories, but the real-life uncertainly that darkens Hong Kong’s prospects. “Twenty years into the handover, the Sword of Damocles that hangs over the city’s heads is inching ever closer,” they write.