Review | Biography of Singapore prime minister Goh Chok Tong dwells on his differences with Lee Kuan Yew

- A telling episode in story of Singapore’s second prime minister highlights the ‘climate of fear’ in the nation in the years before he took power

- The book plays up his governing style, a contrast to that of his political godfather, who wanted Goh to be more Machiavellian and less ‘kind and gentle’

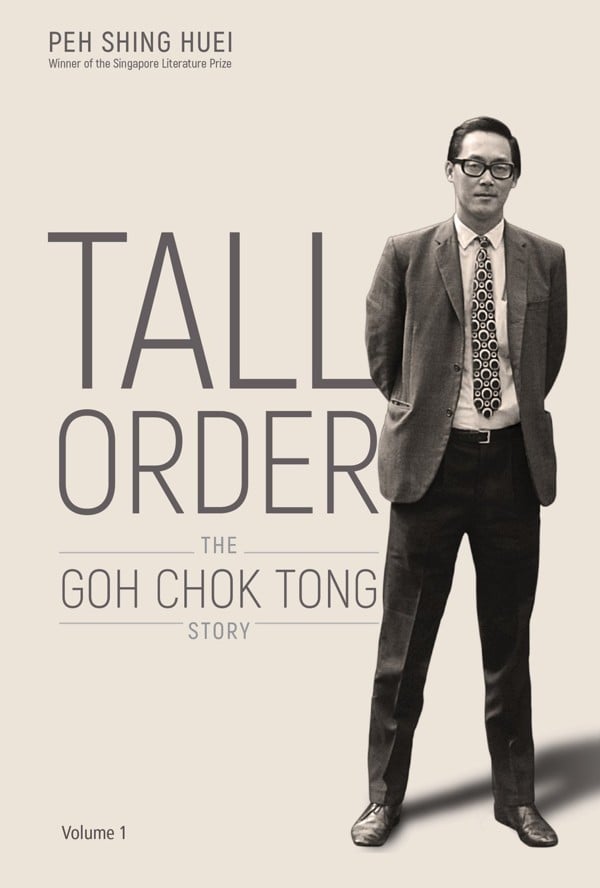

Tall Order: The Goh Chok Tong Story, by Shing Huei Peh, World Scientific, 4 stars

In one of the more dramatic scenes peppered throughout the first biography of former Singaporean prime minister Goh Chok Tong, an academic steps into his office in 1987, three years before Goh took over power from his political godfather, the legendary Lee Kuan Yew.

“She was looking around and seemed somewhat nervous,” Goh is quoted as saying of his visitor in the first volume of the authorised biography, titled Tall Order: The Goh Chok Tong Story. “I asked why and she said, ‘There is a climate of fear. The ISD is everywhere’.”

The acronym refers to Singapore’s Internal Security Department, the island nation’s domestic intelligence agency, once notorious for cracking down on critics of the long-governing People’s Action Party (PAP). Goh’s encounter with the academic, a friend of his from their university days, came as a huge shock to him, even though, as Singapore’s first deputy prime minister at the time, he probably should have known better.

“I knew that there was this fear element,” he tells the book’s author, Peh Shing Huei. “I just did not know it was that bad, that pervasive, that even lunch with me would be scary.”

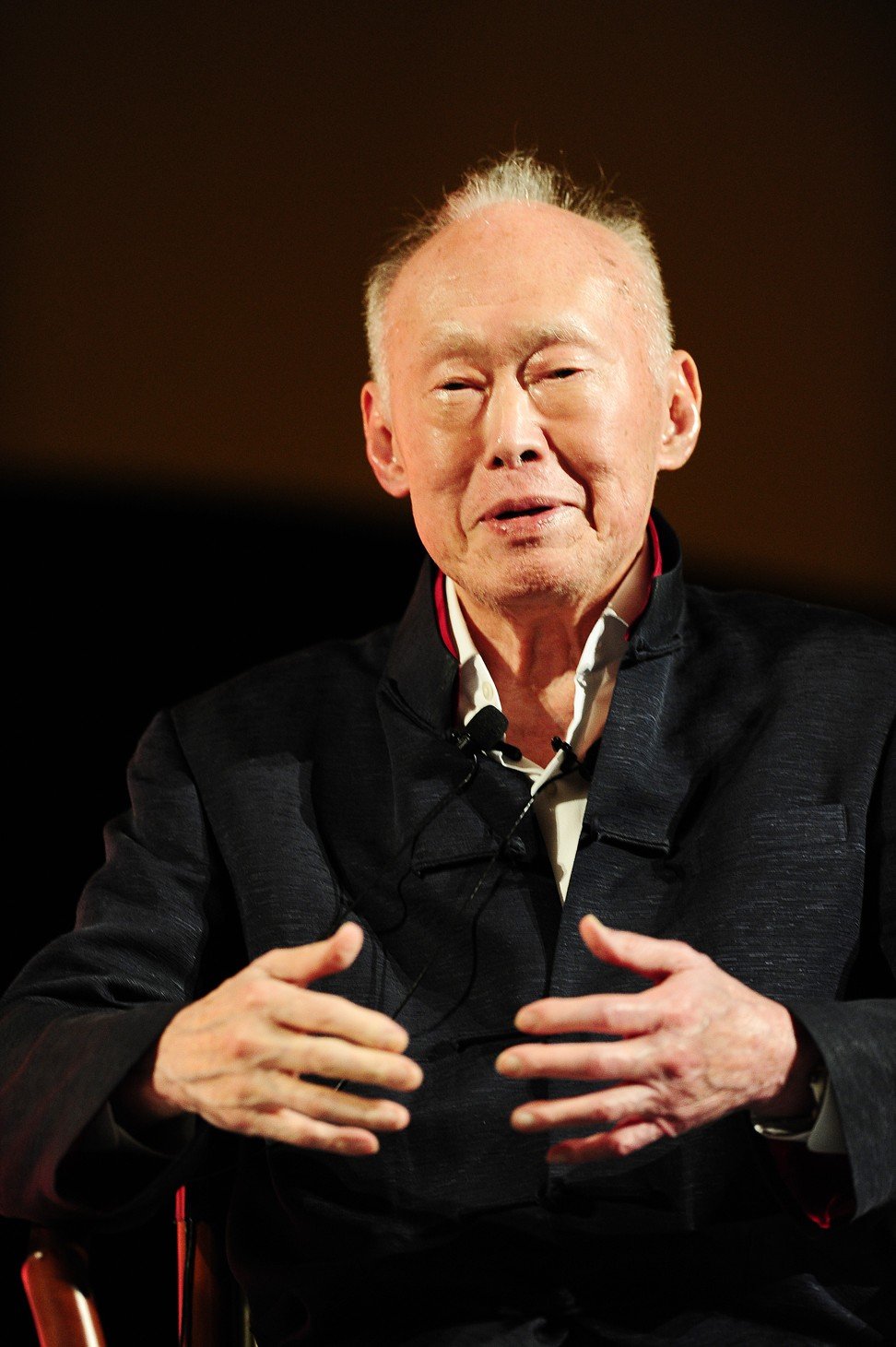

The anecdote suggests Goh was a very different leader to Lee, who governed modern Singapore in a distinctly authoritarian style for 31 years. In fact, Goh recalls his meeting with the academic as “an instrumental moment” in shaping a new vision for the country. The following year, when then-US president George H.W. Bush expressed his desire for a “kinder and gentler” nation, “Goh found the signature phrase which captured the new Singapore he would lead”, writes Peh.

Not surprisingly, LKY, as Lee was popularly called, disliked Goh’s use of the phrase “kinder and gentler”. As Goh tells it, the words conveyed a sense of weakness in the new leader as well as the PAP. In an effort to change Goh’s mind, LKY gave him a copy of The Prince, the seminal 16th-century text on ruthless governance by the Italian philosopher Niccolo Machiavelli.

Goh read the book but refused to subscribe to its tenets. “I never told him [LKY] I didn’t agree with this way of governing,” he is quoted as saying in the biography. “If I told him, he would say, ‘No, no, you better follow me’. And we would clash. So, I just did things my way.”

Review: Unrest – worth the wait for Singapore literature prizewinner

The contrasting style of Goh’s leadership highlights “a leadership succession story that has since been simplified to one which was peaceful, smooth and even bland”, writes Peh, a former news editor and China bureau chief at Singapore’s premier English-language daily, The Straits Times. “The reality had more kinks than a cursory glance at history would provide.”

The 279-page volume spans Goh’s early life and his political journey from a technocrat to Singapore’s top job. Based on interviews with Goh’s childhood friends, teachers, civil servants, diplomats, grass roots leaders and politicians, the book focuses on themes ranging from political battles and leadership succession to economic downturns.

Born into a poor family in 1941, Goh grew up in post-war Singapore at a time when the country was impoverished and “full of political actors fighting each other over colonialism, socialism and capitalism”, writes Peh, adding: “Goh had neither the personality nor the inclination for the rough and tumble of politics.”

He was, to quote from the book’s jacket, an “improbable prime minister for an unlikely country”. And although blessed with winsome looks and, at 1.89 metres, of unusually imposing height, he was a shy and quiet man whom LKY once dismissed as having “wooden” communication skills.

Equipped with “neither the connections nor the cunning to rise to the top”, Goh’s astonishing transformation from just another civil servant to LKY’s successor was indeed a tall order. He made his way up the governmental ladder through a combination of hard work, perseverance, wit and a sense of political earthiness he didn’t know he possessed.

Having earned a master’s degree in development economics from Williams College in the US state of Massachusetts, he first caught the attention of Singapore’s political elite for steering Neptune Orient Lines, the national shipping company, from a chronically loss-making business to a profitable one in just three years. He entered politics in 1976 and became senior minister of state for finance. By 1979, he had launched a new Ministry of Trade and Industry and went on to head the ministries of health and defence.

Temasek to Singapura to Raffles: Singapore’s early history

Perhaps Goh’s most significant technocratic legacy is “MediSave”, Singapore’s – and evidently the world’s – first national medical savings fund and the backbone of its health care system. Although LKY’s idea, it was Goh who turned it into reality. And not by implementing it regardless of public opinion, as his mentor suggested, but by successfully launching a nationwide public relations campaign that helped win support for the plan.

That success, writes Peh, “would translate into a signature policy of Goh when he became Prime Minister later, as he embraced participatory democracy as a key plank of his leadership”.

According to Peh, Goh granted unprecedented access to him and a small team of writers who collaborated with him on the book. For the first time ever, writes Peh, Goh has revealed many of his private conversations with LKY.

Although LKY publicly criticised him on several occasions, “I never doubted that he wanted me to succeed”, says Goh. LKY, he adds, did not want to bequeath his office to his son, Lee Hsien Loong, who became premier after Goh stepped down in 2004. “The public conclusion was that he [LKY] wanted me as a seat warmer,” says Goh. “But I knew him and I went in knowing … he was looking for a real successor outside his family.”

Goh’s biography combines an accessible narrative style with lightly worn but meticulously researched journalism. No date has yet been set for the second volume, which will focus on the 13 years of Goh’s premiership to the present day. The sequel promises to be a compelling read, especially if it’s as energetic in its aspirations as the first volume.