Exclusive | In China’s Motown, Dongfeng Motor epitomises how state ownership thrives, evolves under capitalism

- For five decades, Second Auto – now called Dongfeng Motor – has been the evolving face of China’s state-owned enterprises

- Now it is facing pressure to change again, as private automobile makers provide a nimbler competition for this massive organisation

Si Fumin spends a lot of time reminiscing about the past and worrying about the future these days.

When he began working as a teenage technician on the car frame line in this landlocked city of Shiyan during the late 1980s, Dongfeng Motor was still known as the Second Automobile Works (Second Auto), a holdover from Mao Zedong’s 1964 diktat to invest in defence, technology, mining, manufacturing and power production to spearhead China’s industrialisation.

For almost five decades, Dongfeng would epitomise the changing face of China’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs), from their formative years, to their rapid growth and globalisation when China joined the World Trade Organisation in 2000, to their maturity.

Now, as China’s economy grows at its slowest pace in a decade with a raging trade war with the United States, state enterprises like Dongfeng must shift gears again to compete against smaller, nimbler private companies.

Nowhere is that transformation displayed more vividly than in Shiyan, about five hours’ drive from Hubei’s provincial capital of Wuhan, along a highway built in 2006.

“Going back 40 years, people in Shiyan were probably the happiest in the province, if not nationwide,” said Ye Qing, deputy head of the Hubei provincial statistics bureau, during a recent interview with the South China Morning Post.

Shiyan, with almost 200 Taoist monasteries and religious sites around it, was picked as the southern counterpart to Mao’s industrial plan to develop China’s own version of Detroit.

The country’s very first car manufacturer, called First Automotive Works (FAW) – following the nomenclature of the prevailing proletariat social system of the 1950s – would be located in the heart of China’s rust belt in northeastern Jilin province.

Shiyan was picked for Second Auto after a decade-long selection process because – as the thinking that prevailed during the cold war went – the Wudang mountains that run east to west through the prefecture would provide a natural shield against enemy attacks.

Second Auto started life as a maker of medium and heavy-duty trucks, the workhorses of China’s road to industrialisation. In its initial days, every aspect of its operation – from design to procurement to production and how it deployed its workers – was managed by the central government.

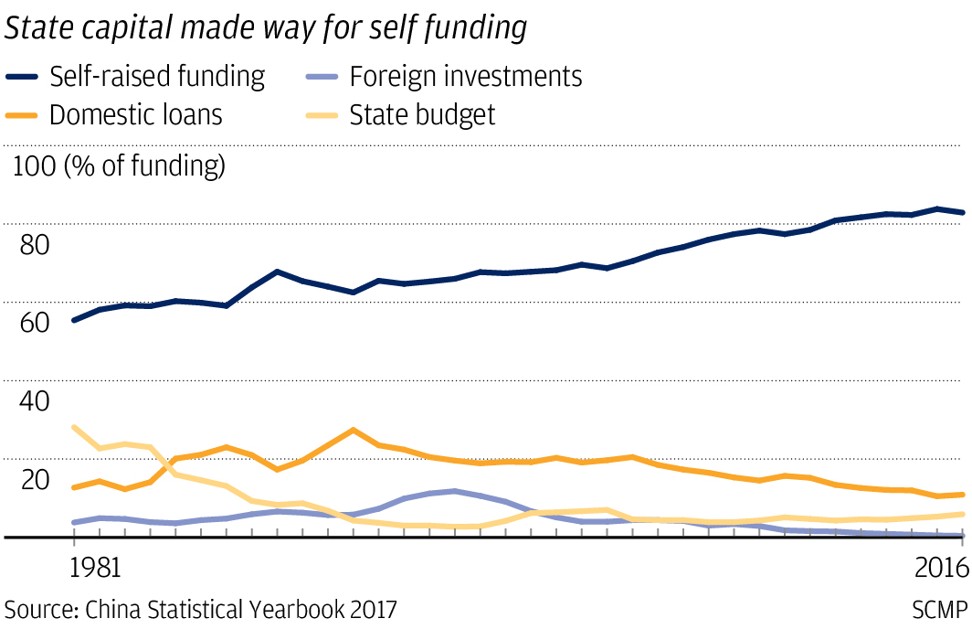

Its transformation began in the 1980s, after former paramount leader Deng Xiaoping unleashed the forces of market capitalism on China’s centrally planned economy in 1978, forcing the country’s SOEs to restructure.

The first step of the reform was to consolidate almost 200 of Second Auto’s operations, from the fabrication of components to the final assembly, under a single state-run enterprise. After 1985, the enterprise was removed from the direct administrative control of China’s central government.

Second Auto renamed itself Dongfeng Motor in 1992 after the easterly winds that aided Three Kingdoms strategist Zhuge Liang to a decisive victory during the Battle of the Red Cliff, fought in Chibi, also in Hubei province.

During the 1990s, while China was negotiating to join the WTO, Chinese policymakers were forcing SOEs to combine into fewer, larger conglomerates to prepare them for global competition.

Under a government policy that required foreign carmakers to assemble in China only through joint ventures – each foreign marque was limited to two Chinese partners – Dongfeng offered its size, sales network, labour force, market access and SOE pedigree as the local partner to foreign carmakers.

Its first venture was forged in 1992 with the French automotive group PSA Peugeot-Citroen, followed by collaborations with South Korea’s Kia Motors, Sweden’s Volvo trucks and Japan’s Nissan Motor and Honda Motor.

Dongfeng also broadened its portfolio of vehicles, reflecting a change in the composition of China’s economy: from heavy trucks used by industry, to minivans popular with China’s nascent private entrepreneurial class, and later to hatchbacks, compact cars and sedans marked with foreign badges for the rising middle-income household.

At the turn of the second millennium, seven out of every 10 vehicles that came off Dongfeng’s assembly line were trucks. By 2012, that trend had reversed: seven out of every 10 vehicles rolling off Dongfeng’s production line were passenger vehicles.

Dongfeng’s transformation showed how a state-managed economic and business ecosystem could exist alongside China’s experiment with capitalism.

The automaker’s controlling shareholder remains China’s government. Its current president, Zhu Yanfeng, a trained automation engineer, is both a business executive and a politician with deputy ministerial rank.

In between his lifelong career in the automotive industry at both FAW and Dongfeng, Zhu served as Jilin’s deputy provincial governor before being promoted to deputy commissar.

Yet, Dongfeng is also a publicly traded company, its shares listed in Shanghai in 2000 and in Hong Kong in 2005. Up to 60 per cent of the stock is controlled by the state enterprise, while minority shareholders include such global investment funds as Invesco, Standard Chartered and Blackrock.

Straddling both the public sector and capitalist markets served Dongfeng well. The carmaker made 3.5 million vehicles in 2014, ranking second among China’s largest automakers.

The carmaker’s sales would reach a record in 2015, with revenue surging 56 per cent to 126.57 billion yuan (US$18.2 billion). Last year’s net profit rose 5 per cent to 14 billion yuan (US$2 billion).

Shiyan itself grew with Dongfeng, becoming the quintessential single-company town. Its population ballooned from a few hundred households during the 1960s to 3.3 million residents during the 2010 census.

It started out as “just a small village, with just a few scattered households and a blacksmith shop”, said a 70-year-old resident surnamed Wang, one of the 25,000 construction workers conscripted from all over China during the 1960s to help develop Shiyan.

“There were no roads at all. We had to clear the hills and fill the valleys. We built all of this,” he said during a recent interview with the Post, gesturing to the roads, residential complexes, malls and factories around the city.

In its heyday, Dongfeng was Shiyan’s dominant employer, with almost 200,000 staff on its payroll. Its production accounted for almost all of the city’s industrial output, and the carmaker provided every imaginable amenity in the city, from housing to schools, hospitals, recreational parks and even the grocery stores. The general manager of the car plant was concurrently the city’s mayor.

“Groceries provided by the company would fill up entire rooms during festive seasons,” said Si, who spent 30 of his 47 years working at the carmaker. “I had enough money to pick up the tab for celebrations with my classmates. Those were the good old days.”

Those days may be in the rear-view mirror now. Shiyan’s population had been shrinking gradually ever since Dongfeng relocated its main passenger car plant to Wuhan in 2003. The carmaker would later broaden its production to Xiangfan in Hubei province, and Guangzhou, leaving only the truck assembly in Shiyan.

For Shiyan native Liu Tao, the writing was already on the wall when he was still in school. As soon as he graduated with a machinery degree in 2000, he left his hometown and went straight to Shenzhen in southern China, lured by promise of opportunities for small, private entrepreneurs.

The former fishing village near Hong Kong was the test bed for Deng’s experiment in capitalism, where its “animal spirit” made it the home city to such world-class private-sector champions today as Tencent Holdings, DJI, Huawei Technologies and Ping An Insurance Group.

Liu helped set up Shenzhen SV Automation Technology in 2006, providing industrial robots and machinery to the manufacturing industry.

“There were lots of [business and personal development] opportunities at that time,” said Liu, 39.

As a Shiyan native putting down roots in Shenzhen, Liu recognised what was holding back his hometown.

“The working efficiency in Shenzhen is particularly high,” he said. “When you apply for a subsidy, you get it quickly, up to 20 per cent of the contract value. But the procedure is more complicated and slower here” in Shiyan, he said.

Still, Liu moved back to Shiyan two years ago to head SV Automation’s local unit, overseeing the sale of industrial robots to Dongfeng’s truck assembly and to other component suppliers. After struggling for a year, he broke through and secured 8 million yuan (US$1.1 million) in orders from Dongfeng and other suppliers.

“The local automation level is far behind the coastal regions. [Local firms] just take a wait-and-see attitude, unwilling to try a large-scale application” of new technology, he said.

For state-owned firms like Dongfeng to survive in the long run, they’ll have to adopt more of the practises of their private sector competitors, whether foreign or domestic.

“China’s state-owned automakers are facing a life or death situation,” said Li Jin, the chief researcher at the China Enterprise Research Institute in Beijing.

Chinese automotive SOEs must compete against Toyota, Volkswagen and all the global automakers that are clamouring to remove foreign ownership limits in China by 2022.

Policy decisions emanating out of Beijing have only added to the pressure on automotive SOEs.

In May, the Chinese government cut the tariffs on non-US imported vehicles by 46 per cent. But the biggest threat to the state-owned automakers comes from the country’s pledge to completely remove foreign ownership limits, Li warned.

China’s state-owned automakers including FAW, Dongfeng and Changan earn most of their revenue from their foreign ventures, but their technical gap with their foreign counterparts – from steel sheeting to efficient engines – remains wide, Li said.

“Dongfeng, for instance, has set up many joint ventures,” he said. “A fairly big chunk of its production is original equipment manufacturing [OEM]” which is marketed by their partners, Li said.

“While foreign partners earn large profits [on the OEM equipment], it has become very hard [for Dongfeng] to enlarge or strengthen its own brand.”

Li expected a reshuffling of state-owned automakers in coming years.

It has long been rumoured that China’s three largest state-owned automakers will merge to create a national champion, similar to the consolidation in such industries as train manufacturing and shipbuilding.

The rumour resurfaced late last month when FAW received a 1 trillion yuan (US$144.1 billion) credit line from 16 state-owned banks, though there has been no word from FAW of how it would use the money.

The government is also enticing private investors to help restructure the state sector.

Beijing unveiled last year a mixed ownership programme, whereby private capital was invited to invest in state companies to help them modernise and become more competitive.

China United would be the first of six SOEs picked by the economic planning agency for mixed ownership in a sector whose combined 2017 revenue reached almost 7 trillion yuan (US$1 trillion).

The remainder are China Southern Power Grid, Harbin Electric, China Nuclear Engineering Group, China Eastern Air Holding and China State Shipbuilding.

Dongfeng itself is also adapting to the changing times. During the Beijing Auto Show in 2010, the carmaker unveiled its concept of an electric vehicle, with a plan to bring it to market by 2015. Eight years later, it announced its concept for the Kuro all-electric sports-utility vehicle (SUV), which is set to roll off the Shiyan assembly line in 2019.

Dongfeng would own half of the venture, with the annual capacity to make 120,000 vehicles, with the remaining 50 per cent split equally between Nissan and Renault.

Si, a Dongfeng man like his father before him, is taking all these changes in stride. More change portends an upheaval at Dongfeng, perhaps the biggest he has seen in his career, he said.

Unlike many middle-aged auto workers, he has taken up sculpting as a hobby, spending most of his spare time making pottery.

Working from a studio converted from an abandoned workshop, Si and his friends are lobbying the local government to preserve Shiyan’s old factories – the second homes for his generation, and his father’s – to turn them into a community art centre.

The old glory days “are gone, and will not come back any more, no matter how much you miss them”, he said, adding: “At least, I hope we can keep the spirit [of the older generations] alive” by turning them into something new.