Why Michelle Obama’s biography Becoming was a missed opportunity

- Chinese author Yiyun Li believes readers deserve more than Obama’s use of symbols and clichés

- Obama’s book reflects the perceived need to use language approved by others

By Yiyun Li

Two years ago, I drove my son and a friend of his to an event. They were 15, and discussing her decision not to participate in a poetry contest at her school.

She had read the previous winners’ poems, she said. They were composed of words such as injustice, inequality, empowerment, action and descriptions of police brutality, of which, the girl pointed out, none of the poets would have direct knowledge. (She was right: she goes to one of the most preppy high schools in the San Francisco Bay Area.)

“What I don’t understand is why can’t we write about flowers any more,” she said.

“Of course we can,” my son said. “But …”

He did not finish the sentence. I wondered if the two children were asking if there was still a place for Emily Dickinson in the US? Or what kind of language should we use if we want to be commended, or simply to belong? Even, not to be punished?

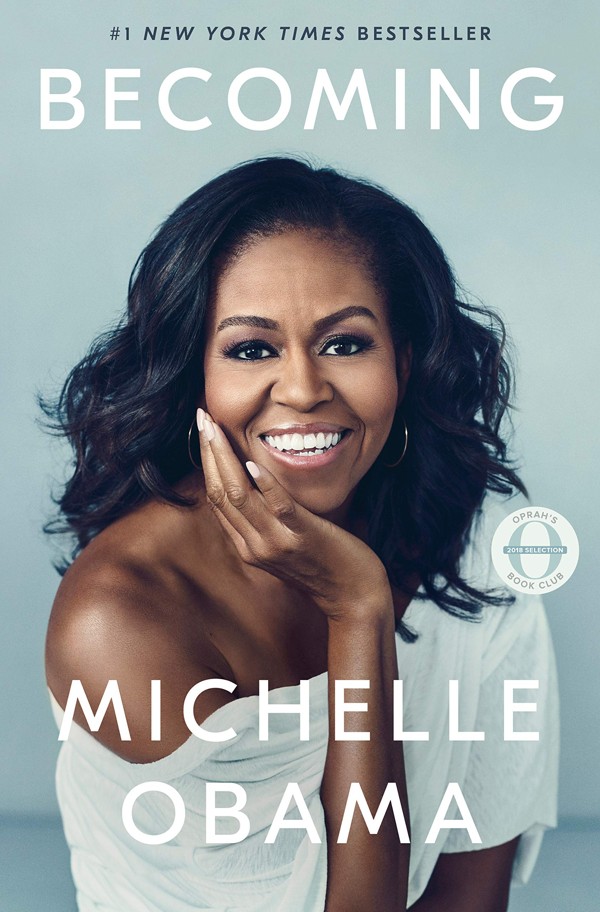

This awareness of the audience may mean that their need becomes the priority. It is perhaps unavoidable in a memoir by a public figure. Michelle Obama’s memoir, Becoming, delivers what it promises: her triumphant life journey from Chicago’s South Side to the White House, with intimate moments to connect with readers, and stirring passages to inspire. But one wishes that someone of her calibre could have defied that convention.

A set of words stood out for me in Becoming: symbol, symbolic, symbolism. The White House vegetable garden “was designed to be a symbol of nutrition and healthy living”. Part of the White House, museum-like, is where “symbolism lived and mattered”.

Queen Elizabeth is “a living symbol and well practised at managing it”. Obama’s presidency was in part “the symbolism of the moment”, and he was held up as “the leader and the symbol for the country itself”. And then there were the restraints Michelle Obama experienced herself having to live as a symbol under the title of first lady.

Students, in reading and analysing literature, often gravitate toward symbols, and many of them, in writing fiction, strive to create characters and actions that can be elevated to a symbolic level. These inclinations come at a cost. Characters conscripted to serve, and to serve as, symbols are obliged to follow a more predictable script.

The problems that have been named in the US – racism, xenophobia, poverty, class inequality, gender inequality – are all too real. But talking about them in symbolic terms turns them into something else: they become a collective narrative that demands to be the most righteous or the only legitimate way to look at the world.

To follow any beacon in any given time without questioning first is as alarming as it is to follow propaganda. Having grown up when communist slogans were printed mandatorily next to birthday photographs and an English textbook started with “Long live the Chinese Communist Party”, perhaps I’m particularly sensitive to words used to dictate how we should feel and think.

Near the beginning of Becoming, Obama writes that she shared a bedroom with her brother, Craig. “The partition between us was so flimsy that we could talk as we lay in bed at night, often tossing a balled sock back and forth through the 10-inch gap between the partition and the ceiling as we did.”

As first lady, Obama visited a high school on the South Side where the students experienced gun violence on a regular basis. The exchange with a student is one of the most candid moments in the book: “‘It’s nice you’re here and all,’ he said with a shrug. ‘But what’re you actually going to do about any of this’?”

Obama acknowledged the students’ circumstances, and then “reminded them those same stories also showed their persistence, self-reliance, and ability to overcome” and “reassured them that they already had what it would take to succeed”.

One cannot but wonder how this would have sounded to the young Michelle and Craig.

Before the 2016 election, I had a conversation with a student from West Virginia. Where she grew up, she said, there was an abundance of widows, not only old women but also middle-aged and young. Men die in West Virginia, was the simple way she put it. Over the years, when reading my students’ work, I have noticed that the heroic and the progressive and the oppressed characters often get promoted on to symbolic height, both in their suffering and in their triumph. The most memorable characters, however, stay life-sized.

Life – for the widows in West Virginia, for the farmers in Iowa, for my son’s friend and the student in Chicago – is not lived as a symbol. Democracy can be treated in all sorts of metaphorical manners; but an election, vote by vote, is a mathematical reality.

Barack Obama names his wife’s book as his favourite of 2018

“When they go low we go high,” is the epitome of symbolic language. Yet what is the unnamed in the slogan?

One has no doubt that Michelle Obama exercises freedom of thought. One wishes that her memoir made a similar demand on its readers. What if she had chosen to forgo the vocabularies of empowerment and inspiration and patriotism? After all, she is a person who can make herself heard. The language she chooses to use will be incorporated into hundreds of thousands of minds and become infallible truth.

Yiyun Li’s memoir, Dear Friend, from My Life I Write to You in Your Life, is published by Penguin