Doomed Hong Kong fabric bazaar’s fans and stallholders fear for future in new premises

Sham Shui Po textiles market is a favourite of design students and bargain hunters. When it is bulldozed for housing and stalls forced to move, customers and traders fear its character will be lost

Do not ask Fiona Hung Wing-sum how many hours she has spent hunting for bargains among the ramshackle alleys of the Yen Chow Street Hawker Bazaar on Hong Kong’s Kowloon peninsula. The former Hong Kong Design Institute (HKDI) fashion student lost count years ago.

Hung, 30, loves the variety of fabrics on sale at the market almost as much as she loves the competitive prices.

Fabric of Hong Kong: exhibition looks back at city’s textile industry

“It’s cheap, and because I have a connection with the vendors I can even indulge in some bargaining,” says Hung, a graphic designer who was sourcing fabric for a photo shoot on a recent grey day. “It’s also a relaxed shopping experience – you don’t have people constantly asking you what you want.”

It’s easy to see why a fan of fabrics would feel like a kid in a candy store at the market, established in 1978 in Sham Shui Po, the poorest of Hong Kong’s 18 districts.

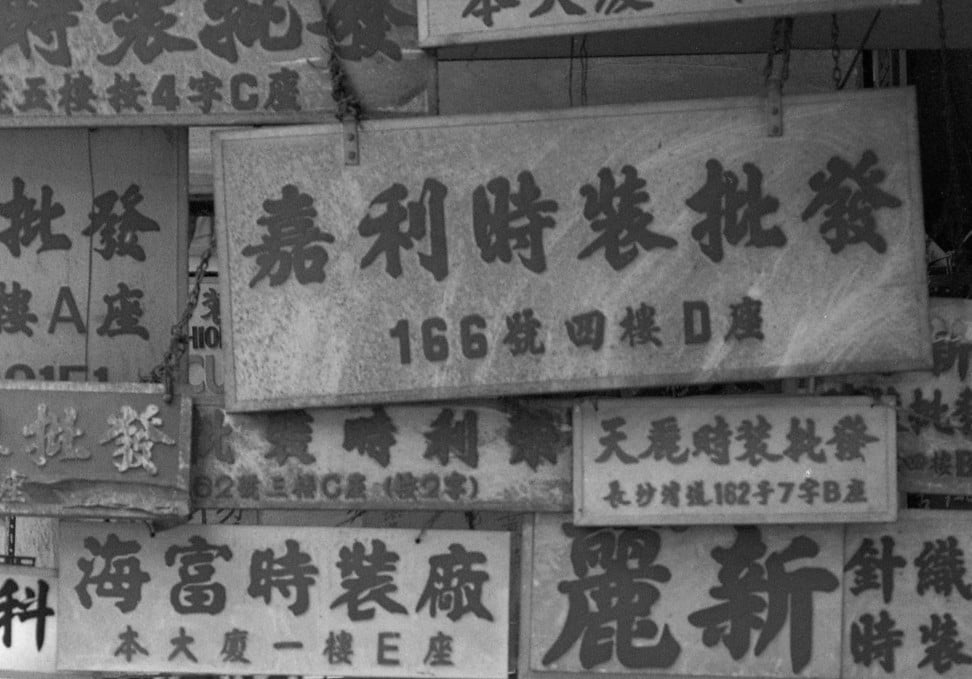

A kaleidoscope of colours jumps from shelves that bulge with rolls of fabric, shimmering sequins, bags of buttons and rows of ribbons; the market’s 20 licensed vendors – and as many unlicensed ones – fill every need. At its peak, almost 200 vendors occupied the space.

But Yen Chow Street Hawker Bazaar is earmarked for demolition. Although a deadline has not yet been given for vendors to vacate it, the market is destined to become another victim of gentrification, following the bulldozing of markets in Gilman Street in Central and Bowring Street in Jordan.

To help ease Hong Kong’s dire shortage of homes, it will make way for a public housing development (200 flats due for completion in 2021-22).

Some fear that with it will go the cheap fabrics and accessories that for decades have lured fashion students, hobby sewers and even famous fashion designers: New York-based Vivienne Tam visits when she is in Hong Kong.

“I’m worried the move will commercialise the market, that it will lose its character,” says Hung.

The government has proposed that the vendors move a couple of streets away to the Tung Chau Street Temporary Market. That is next to a new design and fashion hub launched by the government in January, which house exhibition areas, design studios and a socio-historical exhibition. Space there has also been made available for vendors.

The government offered evicted vendors priority bidding for new stalls and discounted rents.

However, with new monthly rents ranging from HK$500 (US$64) to HK$2,000 a month, compared with a yearly hawker rent of HK$4,600 they are paying now, there is still concern. Compensation has been offered to licensed hawkers who choose not to relocate.

Chan Yu-tung, 85, who has been a vendor at the market for more than 40 years, fears rent at the new space will eventually kill his business.

“They lower the rent for one or two years, but how can we survive after that?” says Chan, also known as “Uncle Tung”, squeezing through rows of fabric (each stall is only three metres by three metres) into a small room, its walls plastered with photos.

Preview of the Hong Kong factories turned design hub The Mills

Hung says although it’s sad the market is closing, she sees the need to strike a balance between conservation and gentrification, an issue close to Sham Shui Po’s heart. The district is one of the city’s most densely populated, and home to large numbers of immigrants and people from ethnic minorities, many of whom live in subdivided flats. It’s also the focus of government urban renewal programmes.

While the market oozes character, it’s also unbearably hot, even on a relatively cool and wet Monday morning in late September. Glaring fluorescent lights dangle precariously between the crammed aisles and a lack of clear signage makes navigating the maze of stalls a challenge.

The atmosphere is both sleepy and shambolic: men with brooms casually sweep away water that drips through cracks in a makeshift roof of corrugated iron and tarpaulins.

Some vendors are starting their day, slicing through material with antique-looking scissors. Others recline in rusty chairs reading newspapers. Radios and televisions crackle in the background.

“Today is better than last Friday, when it was unbearably hot. I could only stay a few minutes, ” says Hung as she chats with a vendor.

Shoppers Elle Fung Mok, 21, and Zoe Lui Wing-chin, 19, students at the HKDI in Tseung Kwan O, agree the lack of ventilation is a problem.

“I love coming here, but do we like it in the middle of summer? Absolutely not,” says Mok.

In a city where industries such as finance, tourism and technology are king, it’s easy to forget the vital role the textile industry has played in shaping Hong Kong.

In the 1950s, it was one of Asia’s biggest textile exporters, and in the 1960s and 1970s, a large number of the city’s population was employed in garment manufacturing (today the textiles industry employs 2,322 workers, or 2.6 per cent of the local manufacturing workforce, according to government statistics for March 2018).

Sham Shui Po was the centre of the garment industry, with thousands of wholesalers, processing factories and shops forming a production chain. Chan remembers it well.

“Dawn markets in Cheung Sha Wan and Shek Kip Mei opened at 6am, the stalls occupying every street and lane … People used torches to hunt for fabric,” Chan recalls.

But the landscape shifted when rising rents and labour costs combined to send factories scurrying across the border to cheaper China.

“Hong Kong started importing cheap and nice clothes from mainland China, and family garment businesses couldn’t compete or survive. We went through a transformation,” says Chan, whose main customer base today comprises fashion students and housewives “who want to make their own curtains, bedsheets and pillow covers”.

As well the new fashion hub announced in January, which is expected to take five years to convert and involves conversion of a block of run-down buildings into fashion studios, production workshops, co-working and seminar spaces, an incubation centre, and a library, there are other factors contributing to the revival of Sham Shui Po.

In 2010, the Savannah College of Art and Design opened in Sham Shui Po, two years after the opening of a Jockey Club Creative Arts Centre nearby. In 2015, the government announced plans to spend HK$500 million over three years to promote local fashion designers and brands.

But Chan says the current government, under Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor, is focused only on attracting a more chic international crowd. “We sell ‘rubbish’ while this new hub will sell regular-priced better products. The government could attract tourists and people who want to learn about the city’s textile past by protecting and nurturing vendors like us … we could become the unique cultural industry of Sham Shui Po.”

Chan says he will quit if he cannot make money in the new location. “I’ve worked for many years. I feel connected to it, so it would be a bit pity if I don’t continue.”

Another vendor, Margaret Li, has been running her family stall for more than 30 years.

“My mother was the licence owner, but she passed away a few years ago, so now my brother and I share the business,” says Li.

She is concerned the new fashion hub, a five-storey podium with a floor area of about 3,600 square metres, will not have enough space to properly display fabric.

“We’ll have to cut the fabric into small pieces to show a sample. The customers cannot see clearly. And the rent will be high.”

Like Chan, Li – whose main customers are also students and housewives – is concerned higher rents will force her to close.

“If I have to move I’ll improve the quality of my products so I can charge a higher price to cover the rent and licence fee,” she says. “But sometimes it’s not about the profit … We like customer happiness and job satisfaction.”

Another visitor to the market is “60-something” Dawn Eikey. Born in the United States, Eikey has called Hong Kong home for the past 35 years. She discovered the market just three weeks ago.

“I love the huge selection and there’s no crowds, so you can take your time. No pressure from sales staff. … I’ve shopped in areas in Sham Shui Po and Central, and in Western Market, but this selection is the most impressive.”

40 years of fashion finished at famed Yen Chow Street Hawker Bazaar

Eikey was not aware the market was to be demolished to make way for public housing.

“If the new place is charging too much rent then we may lose some of the good sellers … I’m all for supporting small businesses,” she says.