What deadly 1918 Spanish flu outbreak taught us, and how world can ready for next pandemic

Some scientists believe the next major influenza pandemic could kill 150 million people, with diabetes, obesity, antibiotic-resistant bacteria and global warming complicating the fight against it

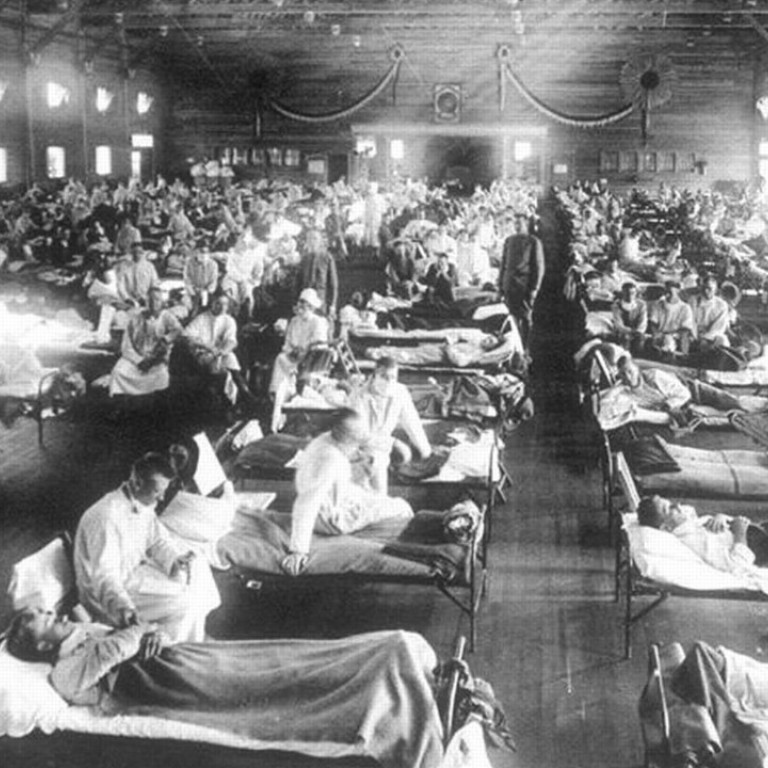

It was the disease to end all others, infecting a third of humanity, killing tens of millions in their beds and prompting panicked talk of the end of days across continents still reeling from war.

One hundred years on from the influenza outbreak known as the Spanish flu, scientists say that while lessons have been learned from the deadliest pandemic in history, the world is ill-prepared for the next global killer.

How 1968’s deadly Hong Kong flu left more than one million dead

In particular, they warn that shifting demographics, antibiotic resistance and climate change could all complicate any future outbreak.

“We now face new challenges including an ageing population, people living with underlying diseases including obesity and diabetes,” says Dr Carolien van de Sandt from the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity at the University of Melbourne.

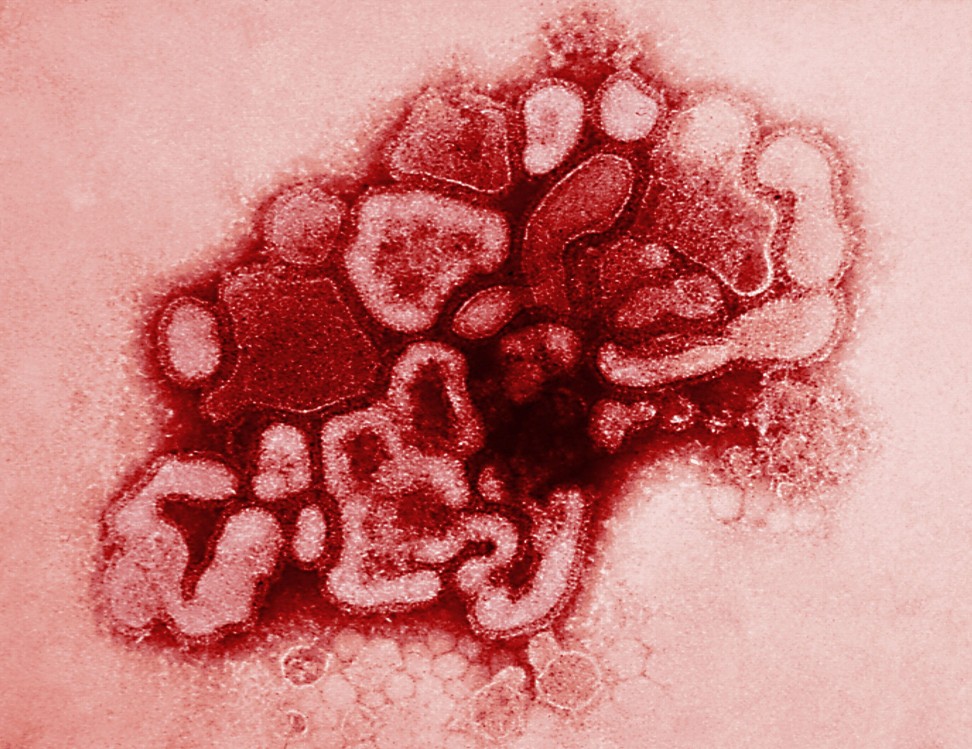

Scientists predict that the next influenza pandemic – most likely to be a strain of bird flu that infects humans and spreads rapidly across the world via air travel – could kill up to 150 million people.

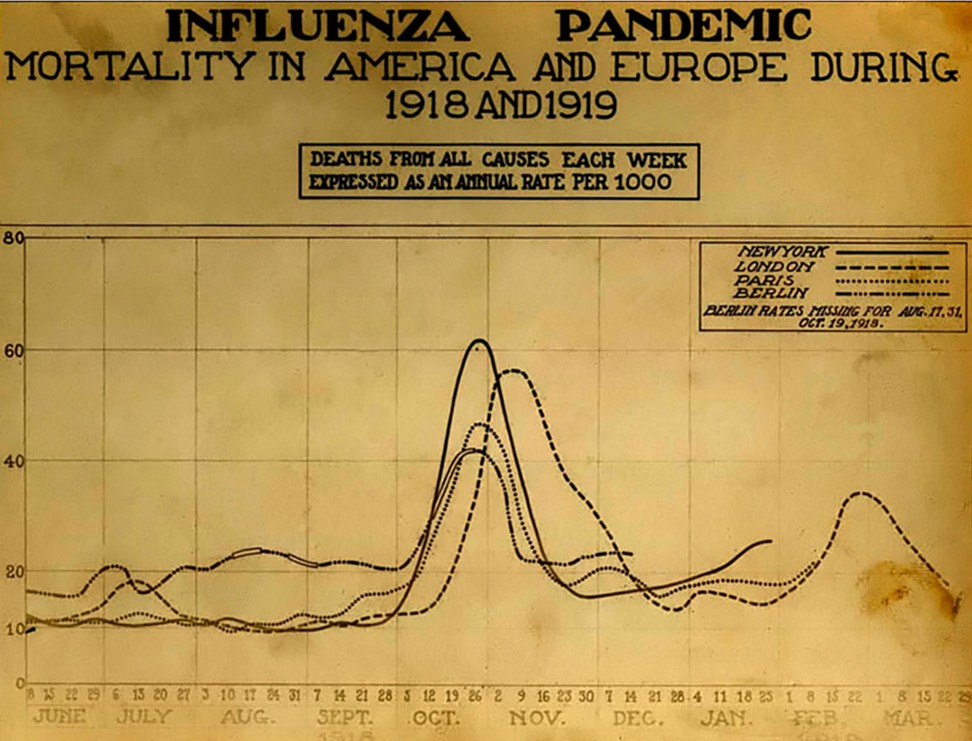

Van de Sandt and her team examined reams of data on the Spanish flu, which tore around the planet in 1918.

They also studied three further pandemics: the 1957 “Asian” flu, the “Hong Kong” flu of 1968 and 2009’s swine flu outbreak.

They found that although the Spanish flu infected one in three people, many patients managed to survive severe infection and others displayed only mild symptoms.

Unlike most nations, which used wartime censorship to suppress news of the spreading virus, Spain remained neutral during the first world war. Numerous reports of the sickness in Spanish media led many to assume the disease originated there and the name stuck.

It is now largely believed that the strain of flu in 1918 in fact originated among US servicemen and killed a disproportionately high amount of soldiers and young people.

Researchers say things will be different the next time.

An important lesson from the 1918 influenza pandemic is that a well-prepared public response can save many lives

In 1918, in a world struggling with the economic impact of global war, the virus was rendered deadlier due to high rates of malnutrition.

A study, published in the journal Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, says the next outbreak will spread in the developed world among a population struggling with record obesity and diabetes rates.

Is Hong Kong ready for the next deadly epidemic?

“What we know from the 2009 pandemic is that people with certain diseases (such as obesity and diabetes) were significantly more likely to be hospitalised with, and die from, influenza,” says Kirsty Short, from the school of Chemistry and Biosciences at the University of Queensland.

The team warns that the world faces a “double burden” of severe disease due to widespread malnutrition in poor nations – exacerbated by climate change – and overnutrition in richer ones.

Global warming could have an impact in other ways.

Van de Sandt says that since many influenza strains begin in birds, a heating planet could alter where the next outbreak emerges.

“Climate change may change migration patterns of birds, bringing potential pandemic viruses to new locations and potentially a wider range of bird species,” she says.

One thing the investigation into 1918 threw up was that older people fared significantly better than younger adults.

The team theorise that this was due in part due to older citizens having built up some immunity through previous infections.

Most of those killed in 1918 died due to secondary bacterial infections, something that antibiotics helped alleviate during subsequent pandemics.

But today immunity to antibiotics is a problem.

“This increases the risk that people again will suffer from and die as a result of secondary bacterial infections during the next pandemic outbreak,” says Katherine Kedzierska, from Melbourne’s Doherty Institute.

The authors cite avian H7N9 – a virus that kills roughly 40 per cent of people it infects, even if it cannot currently pass from human to human.

“At the moment, none of these viruses has acquired the ability to spread between humans, but we know that the virus only needs to make a few minor changes to make this happen and could create a new influenza pandemic,” says van de Sandt.

How the Sars epidemic left its deadly mark on Hong Kong

While the world in 2018, with more than seven billion people, megacities and global air travel, is barely recognisable from a century ago, the team insists there are many lessons the Spanish flu can teach the governments of today.

By nature, pandemic virus strains are unpredictable – if authorities knew for sure which flu was going to spread they could invest in a widely available vaccine.

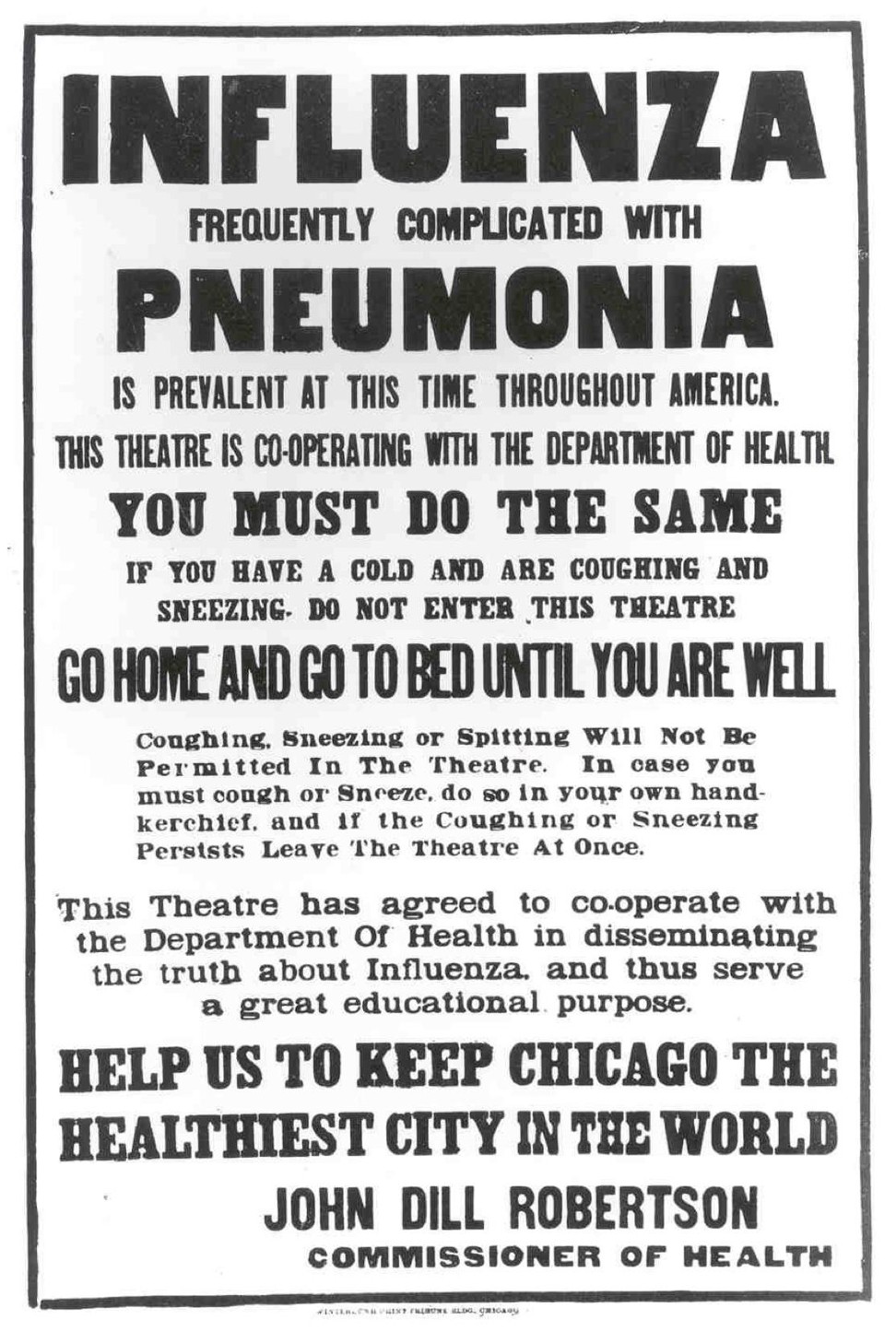

Until a universal vaccine is created, “governments must inform the public on what to expect and how to act during a pandemic,” says van de Sandt.

The study says governments can use the communicative power of the internet to help spread awareness and instructions in the event of a new pandemic.

“An important lesson from the 1918 influenza pandemic is that a well-prepared public response can save many lives,” says van de Sandt.

.png?itok=arIb17P0)