How MDMA, magic mushrooms and LSD help cancer patients cope, and cure addictions

Researchers studying the benefits of taking pyschedelic drugs think they work by removing constraints the brain places on how we see the world

Psychedelic drugs such as LSD and psilocybin (taken in the form of magic mushrooms) are usually associated with the counterculture of the 1960s. The Beatles, for instance, experimented with LSD, and their swirling track Tomorrow Never Knows is an attempt to describe the effects of an LSD trip. Less well known is the medical research conducted on psychedelic drugs during the 1950s and 1960s, and their effects on, for instance, alcohol addiction.

When LSD became a banned Schedule 1 substance in the mid-1960s in the United States, funding dried up, and the research petered out in the 1970s. Although many felt that continuing it would be worthwhile, a government worried about the effects of the drug on young people ensured the psychedelic genie was put firmly back in the bottle.

Illicit drugs Ice, ketamine easy to access for youths in Hong Kong

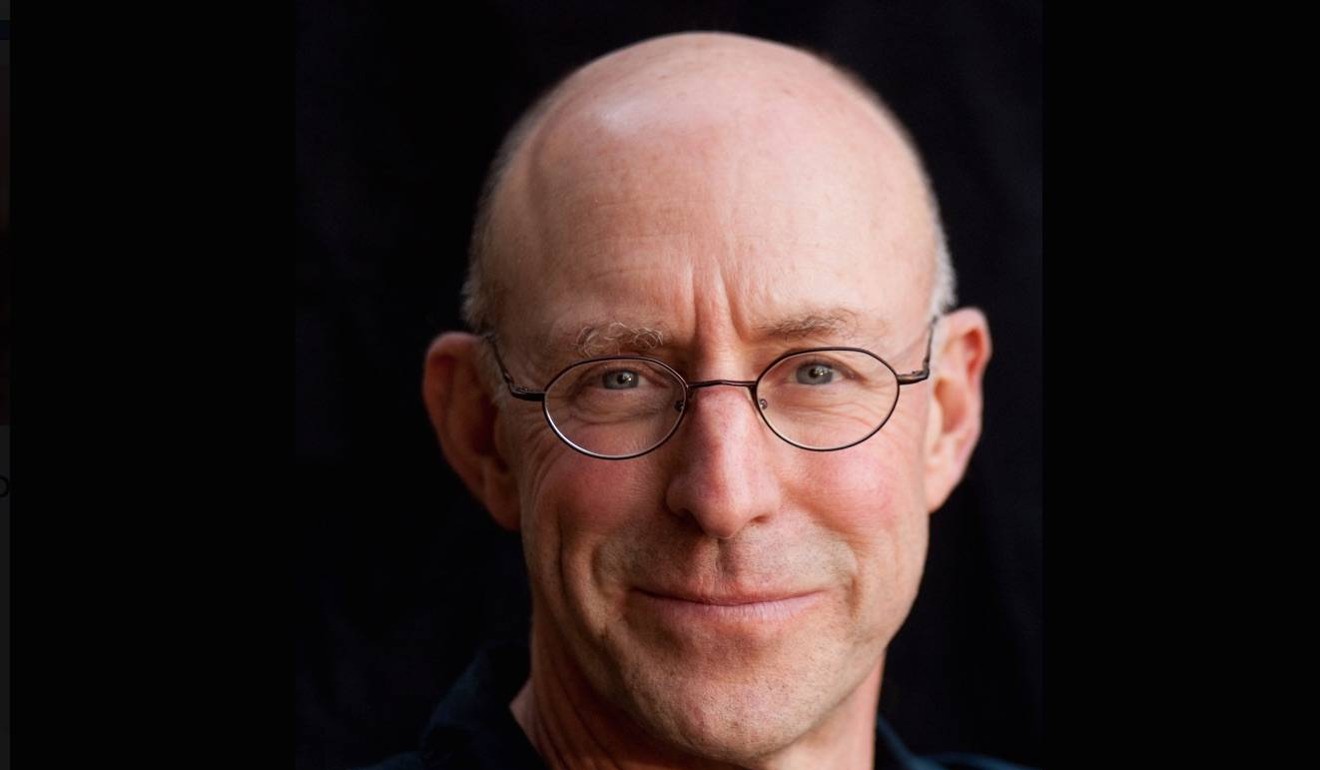

It was not until around a decade ago that it resumed, as Michael Pollan, who holds professorial posts at both the University of California Berkeley and Harvard, describes in his book How to Change Your Mind. Today this research into the medical uses of psychedelic drugs continues in institutions such as New York University and London’s Imperial College.

Researchers are looking into ways psychedelic drugs can help terminal cancer patients cope with their illness, cure addictions such as smoking and alcoholism, and provide relief for those suffering from depression and, in the case of MDMA (known as Ecstacy), post-traumatic stress disorder.

Volunteer patients take psilocybin in medically supervised “trips” in adapted hospital rooms and afterwards document and discuss with medical staff their experiences, and the beneficial effects of the drugs, if any.

The results, says Pollan – who took LSD and magic mushrooms as part of the research for his book – show that the medical use of such substances can improve patients’ well-being. Psychedelic drugs are not known to be addictive, and patients usually need to take the drug only once to reap the benefits.

Chinese parents feed stimulants to teens to pass entrance exams

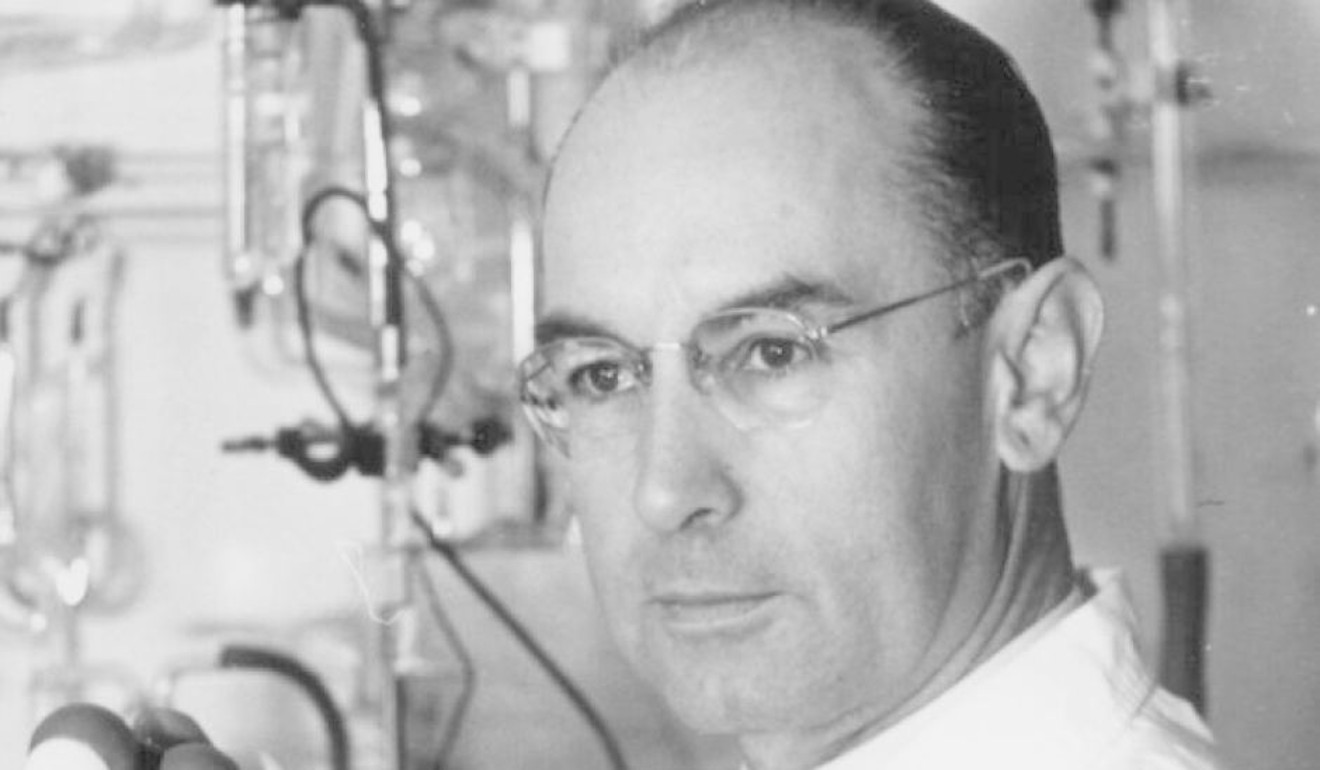

LSD – lysergic acid diethylamide – was first synthesised by Swiss chemist Albert Hoffman in 1938 as part of a medical research programme. Its psychedelic properties were not discovered until 1943, when Hoffman accidentally ingested some.

Hoffmann experienced a typical acid trip, a kind of mystical, ineffable experience during which hallucinations occur, peaceable feelings arise, the sense of the self dissolves, and the user feels part of something larger.

LSD was used as a psychiatric medicine after 1947, but its adoption by the counterculture in the 1960s, spurred by writers like Ken Kesey and professor and self-styled acid guru Timothy Leary, who thought it would lead to a more peaceful world, resulted in it becoming a widely used recreational drug.

LSD was seen as a shortcut to a mystical experience, and played a large part in the love-and-peace ideology of the 1960s. Psilocybin, which is found in certain mushrooms, has a similar psychedelic effect to LSD, and was part of the medical research programmes, as well as seeing heavy recreational use. Psilocybin is usually used in today’s clinical trials.

So how do psychedelics work to help patients? The experience can change a patient’s world view, and give an addict the will and the desire to break their addiction, or someone with a terminal illness the strength to face up to death. It’s a matter of neuroscience, says Pollan.

Neuroscientists think psychedelic drugs may remove the constraints that the brain places on our conscious experience, thereby allowing us to experience the world differently and, by most accounts, more positively.

Changing times at Shek Kwu Chau, Hong Kong drug rehab island

Unlocking what it means to be conscious is one of the big challenges science faces in the 21st century. To simplify a complex – and scientifically controversial – theory, some neuroscientists think that our consciousness is the product of a hierarchical process: certain parts of the brain impose constraints on the way we perceive the world, and those constraints order our perceptions of the world. In short, we perceive the outside world the way the brain has been programmed to let us perceive it.

Evolution has resulted in the brain deciding that a certain world view – the acceptance of a particular reality – is beneficial to our survival. This, among other things, usually involves placing our individual self at the centre of that world.

Psychedelic drugs, Pollan says, break down those constraints, allowing information to flow freely into our brains, and upsetting the hierarchy.

“In this model, the default mode network – which combines parts of the pre-frontal cortex, where our executive function is, with all the centres of memory and emotion – is, in the view of many neuroscientists, our ‘orchestra conductor’,” Pollan says in an interview with the Post.

The drugs foster a shift in perspective. You see your life and its problems differently

Brain scans show that this network sees a significant drop in activity if a subject has taken psychedelic drugs, allowing us to perceive the outside world without interference.

As writer Aldous Huxley put it in 1954, psychedelics open the doors of perception. When this happens, the network becomes unregulated and the sense of the self dissolves.

“We are suddenly in an ego-free state,” says Pollan. “The ego is a sequence of barriers – walls between you and nature, you and other people, you and your own mind, you and your subconscious. When you lower those barriers, more information gets in. You feel that you are part of a larger entity.”

It’s possible, he says, that psychedelics allow us to see the world as it is rather than how our brains want us to see it.

The different world view the patient has while under the influence of psychedelics can bring about changes in behaviour when the drug wears off.

The biohackers who swear by supplements to boost brain health

“Being an alcoholic, or being depressed, you are looking at life from a certain perspective, and it’s destructive,” Pollan says. “The drugs foster a shift in perspective. You see your life and its problems differently. Changing that perspective and seeing things from a different point of view can be constructive.”

Alcoholics and smokers, for instance, while under the influence of psychedelics, may realise that they should not be harming their bodies – and they bring this realisation back to their everyday reality when the drug fades. Patients dying from cancer who have been part of the research have said the experience – the glimpse of a different reality – makes it easier for them to face death.

The treatment is only suitable for a certain type of mental problem, Pollan notes – it won’t solve all the world’s problems, as Timothy Leary thought. “The mental problems that the drugs appear to work well on share certain trademarks. There’s a kind of stickiness – you are mentally stuck in a negative groove.

“For instance, you can’t imagine getting through the day without another cigarette or drink. You can’t imagine ever finding anyone worthy of love. You see yourself in a certain negative way, and that view is reinforced by your behaviour, and the predictable results of your behaviour – you’re stuck in these grooves. What the drugs do for many people is dissolve those grooves temporarily. It’s liberating,” Pollan says.

How meditation can make Hong Kong healthier

The problem with psychedelic experiences, as any first-year philosophy undergraduate will tell you, is their veracity – just because something feels real doesn’t mean that it is real. What if patients are basing their newfound positive perceptions on an illusion?

Pollan agrees veracity is important for metaphysics, but says most in the medical profession aren’t concerned with it. Their approach is pragmatic – the psychedelic experience helps the patients, so it doesn’t matter whether it is a true experience or an illusion.

”People can’t begin to answer this. No one knows. But ... if, for instance, a psychedelic experience allows a cancer patient to die with equanimity, who are they to take that away from them?” says Pollan.