How gender stereotyping in adverts is bad for women and men, and why it persists

Misrepresentation of the sexes in advertising remains widespread in Asia, holding back social progress. Brands that promote themselves this way stand to lose customers, experts say

How often do we see mature women, older first-time mothers, or plus-size females being portrayed positively in advertising? Or women in general being featured in leadership roles, for that matter?

We all know the answer: unrealistic portrayals of women – and men – persist. And this gender-biased advertising encourages discrimination based on age, ethnicity, ability, and sexual orientation.

Bias against hiring mothers reflects social prejudices

Harmful stereotypes in advertising have remained unchallenged for decades, as the advertising industry has failed to authentically reflect the diversity of the world we live in.

A 1999 international study by, Adrian Furnham and Twiggy Mak, both of University College London, showed that most businesses and brands used men to deliver authoritative voice-overs in advertisements. Women were shown only as users of products, says Puja Kapai, associate professor of law at the University of Hong Kong and convenor of its Women’s Studies Research Centre.

She says such gender-stereotypical portrayals are still prevalent two decades on.

Her criticism echoes the findings of a recent independent analysis of advertising in China, India, and Indonesia conducted by international consumer goods company Unilever. The study shows that 62 per cent of adverts do not portray women in significant roles – other than demonstrating a product – and only two per cent put them in aspirational or leadership positions. Furthermore, only 13 per cent of adverts featuring women could be considered positive and progressive, and the same went for only 18 per cent of those featuring men.

In China, only six per cent of adverts featuring women show them in a progressive way, and only 11 per cent showed men in a progressive way. In addition to this, 73 per cent feature a woman with no significant role.

We must work harder to be more representative and inclusive in our portrayals of all people

The Unilever study also offers an insight into the flawed perception of males, with only nine per cent of adverts showing them in charge of children or domestic work, and just three per cent depicting them as caring fathers.

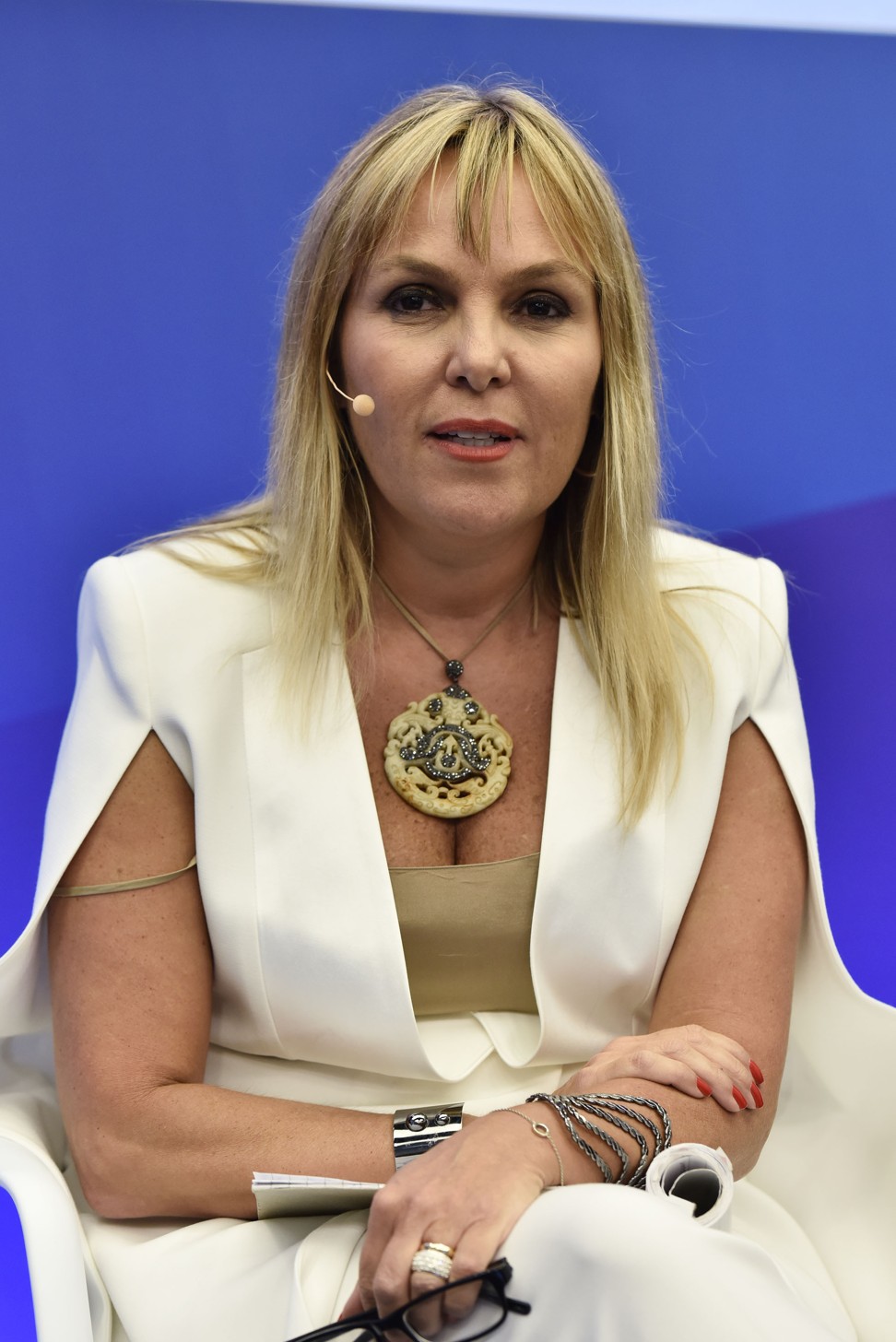

The findings are a reminder that, while the advertising industry has made positive strides in eliminating the most harmful and regressive stereotypes of women and men, there is still much work to be done. The industry is falling short when it comes to depicting people in roles that are modern or forward-looking, says Aline Santos, executive vice-president of global marketing at Unilever, and its global head of diversity and inclusion.

Santos recently addressed an international conference in Singapore to urge the marketing industry in Asia to push harder for more progressive portrayals of women and men in advertising. She believes that the continuing gender imbalance in advertising is harming society because “it means we’re not showing people in an authentic, positive, and representative way”.

Kapai fears that the consequences are harmful to both sexes. Not only do they undermine women’s self-esteem, and their mental and physical health, but they also subject men to the pressures of masculine stereotyping. As a result men will develop unrealistic expectations of women, and how they should behave.

These adverts may seem innocuous at first glance, but Kapai points out that patriarchal structures and gender-based violence are still entrenched in Asia. Gender misrepresentation makes women even more powerless, which can have dangerous consequences, she says, as well as impeding social progress.

It particularly affects young people, who are exposed to the influences of such advertising more than the general population because they are heavy users of social media.

Hong Kong must act to end ‘motherhood penalty’ for workers

Santos believes brands can make a difference, and some are already doing so. Their efforts to remove stereotypes from advertising include: addressing toxic masculinity and outdated stereotypes by making local market campaigns more nuanced; challenging societal norms and gender perceptions; celebrating and championing multi-dimensional masculinity; empowering women to make their presence count, and; spreading positive messages around equality and tolerance.

“Our industry has worked hard to remove harmful stereotypes and must continue to do so … We must work harder to be more representative and inclusive in our portrayals of all people, considering not only gender, but other dimensions such as race, class, language, and sexuality,” Santos says.

She says brands that do not change their ways risk losing customers to the brands that do. Of course, changing long-established behaviour takes time.

“The primary issue is that, while there are great examples of brands incorporating more positive portrayals of women in their advertising, progress is only happening in pockets. We need to systemise the change … This is about massive and fundamental changes in strategy,” Santos says.

Much of the problem is because of our unconscious biases, she says. “It’s part of our nature. It’s been conditioned into us since we were little babies, so breaking these biases is a difficult thing and a challenge.”

Her research shows that progressive advertising is 25 per cent more impactful with consumers, and improves a brand’s credibility by 21 per cent. “People are telling us that these types of adverts are 16 per cent more relevant and 25 per cent more enjoyable,” she adds.

With the advent of the #MeToo movement, ordinary people all over the world are calling for change and seeking to hold big corporations to account, and Santos says: “Advertising must reflect what’s going on in society, and it must lead the conversation [concerning gender stereotypes].”

Activist tackles prejudice against sex violence victims

Kapai suggests that gender stereotyping in advertisements stems from the fact that most brand managers and creative heads of marketing agencies are men, and that there needs to be greater gender diversity in the top tiers of these companies to make them more gender-equitable.

Kapai says power lies with the booming Asian youth population under the age of 30. They wield the numbers to help reduce gender stereotyping in adverts, but educating them about harmful stereotypes must begin in preschool.

She says it would help if advertising standards authorities or regulators set out codes of practice for advertisers and businesses and publicised ways to complain about harmful stereotyping.

Bau Chung Sze-wan, leader of the Hong Kong chapter of Lean In, a worldwide community group that supports female empowerment, says it is the responsibility of every individual not to denigrate women.

“We all need to be aware of the fact that every negative description, news feed or comment we put out there will only add to the imbalance of gender representation.” says Chung. “Nowadays every ordinary individual has the power to influence public opinion in their own way, so we have to act responsibly on social media.

“For example, we have to appreciate that when a woman acts tough at work she is not being bossy, because women can be just as decisive as their male colleagues.”

There should be an end to all unfair and stereotypical portrayals of women, Chung says.