Pregnancy problems: lab breakthrough may help scientists understand pre-eclampsia and other complications

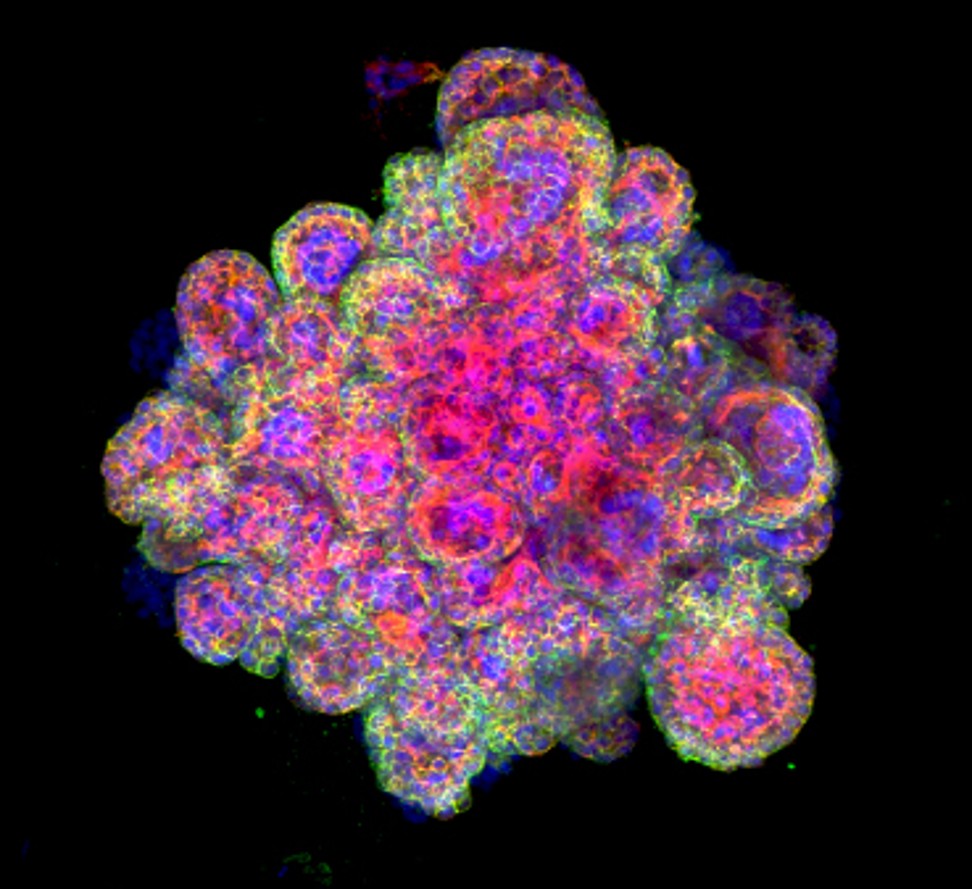

- Scientists grow mini placentas that secrete pregnancy hormones and proteins

- The breakthrough will help them understand the changes that occur in early pregnancy and could eventually prevent life-threatening conditions

Scientists have unveiled a model, lab-grown organ that replicates the early stages of the placenta. They say it could transform our understanding of reproductive disorders and complications during pregnancy.

As many as 300,000 women die every year around the world from preventable conditions linked to pregnancy and childbirth, according to the United Nations.

Many of these deaths are down to what happens to the placenta – a temporary organ connecting the developing baby to its mother’s womb – during the first few weeks of pregnancy.

But because the changes to both occur deep within a woman’s body, the placenta is one of the most poorly understood organs.

Now, however, researchers at Britain’s University of Cambridge say they have managed to grow placentas outside the womb – and that the organs that continued to develop for over a year and which performed most of the primary functions of the organ.

They say the breakthrough creation of these placenta models – or organoids – provides a window into changes that occur during early pregnancy and could ultimately save women from potentially life-threatening conditions as their fetus grows.

“The placenta is the first organ that develops and is the least understood,” says Ashley Moffett, from the university’s department of pathology.

Another placenta miracle: stem cells repair preterm babies’ lungs

“It supplies all the functions for the baby in utero, it protects the baby and it secretes a load of hormones and other products – if any of these functions don’t work, then the pregnancy will not be successful.”

Often, medical research for products or breakthroughs intended for humans beings is performed on animals. But human and animal placentas are too different to provide a good model for research, and the last 30 years have seen increasing efforts to grow placental cells outside the body.

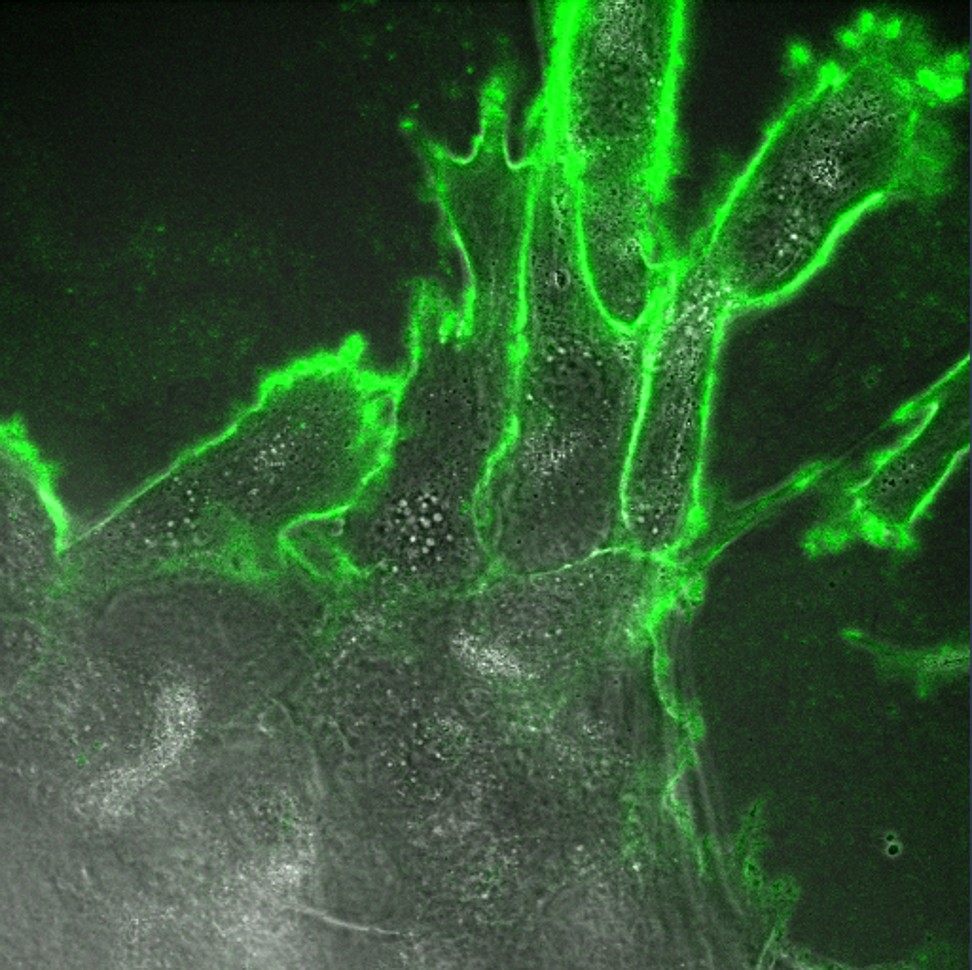

Moffett and the team nurtured a miniature model placenta under laboratory conditions by identifying and isolating cells from the trophoblast – the membrane that provides nutrients to an embryo and helps the placenta attach to the uterus.

Pay-as-you-freeze egg storage cuts IVF costs for career women

These organoids were able to survive long-term, and even began to secrete the same proteins and hormones that would affect a mother’s natural functions during pregnancy. Even over-the-counter home pregnancy tests identified the presence, for example, of the hormone HCG.

“We are now pretty certain that these are trophoblast cells – but do they function? Do they do the things that a placenta does?” Moffett says.

The team said the mini organs would help doctors understand how perinatal complications develop, such as pre-eclampsia – a life-threatening condition where the mother’s extreme high blood pressure can only be alleviated by giving birth.

The condition is known to be linked to the formation of the placenta. In 2015 it killed nearly 47,000 women worldwide, according to the World Health Organisation.

A peek into China’s thriving black market for human placentas

By having models that mimic the placenta to experiment on, researchers hope to isolate certain chemicals or signals given off during early pregnancy, allowing the development of a test for women who could be at risk.

“This can now be done using this experimental model in a dish,” Moffett says.

Commenting on the study, which appeared in the journal Nature, Vivian Li, group leader of the Francis Crick Institute, called the mini organs an “exciting breakthrough”.

“The ability to culture these mini placentas in the dish has opened up the possibilities for more complex studies,” said Li, who was not involved in the research.

.png?itok=arIb17P0)