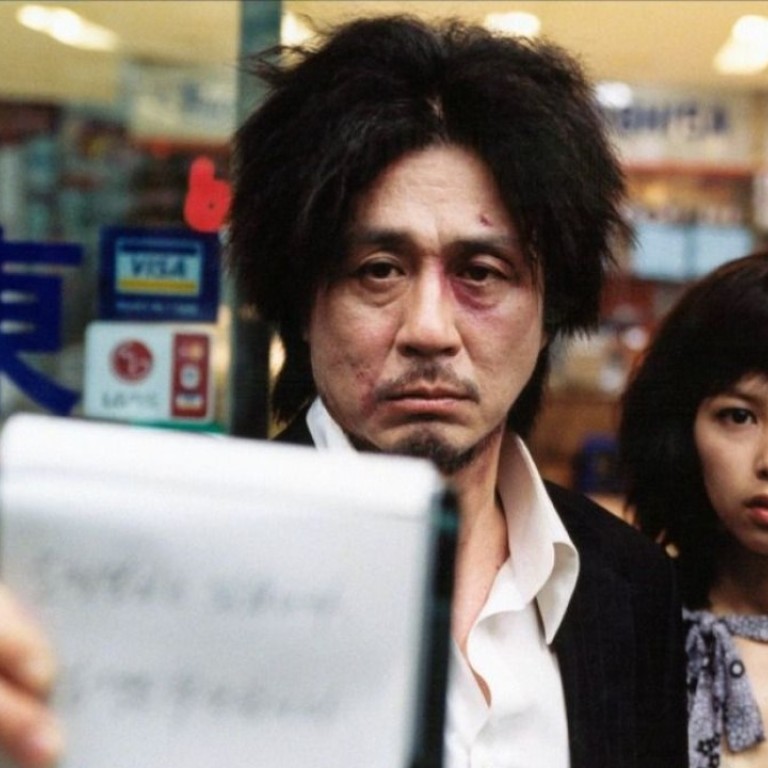

Oldboy: Park Chan-wook’s 2003 tale of revenge puts the bestial core of humanity centre stage

The brilliant but disturbing South Korean film remains a strikingly original work

Fifteen years after its release, Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy remains a strikingly original work. Although known for its sporadic scenes of grim violence, which today seem relatively restrained, the film is philosophical rather than exploitative, with a focus on revealing the bestial core of humanity that civilisation usually manages to keep in check.

Philosophy does not work well in film unless it’s tied to a strong narrative, and the story, co-written by Park but based on a Japanese manga by Nobuaki Minegishi and Garon Tsuchiya, is satisfying. A cataclysmic star turn by veteran actor Choi Min-sik – including a scene in which he eats a live octopus – is so intense, it makes what is actually a psychological fantasy seem real.

Film review: The Handmaiden – Park Chan-wook’s lavish erotic thriller

The clever script follows an unpredictable course that reaches a perfectly rational, if thoroughly disturbing, conclusion. It begins with Dae-su (Choi) finding himself locked in a private prison for no apparent reason. As the years tick by, Dae-su gives up trying to work out why he’s been imprisoned and starts to plot revenge on the unknown figure who put him there. After 15 years, Dae-su is released – again, for no discernible reason – and turns detective to find out who ruined his life, and why. Random events suggest, however, that he’s still not entirely free of his captor.

Revenge is a primitive emotion that fulfils no rational function, and it proves the perfect foil for Park to explore what Joseph Conrad called our primal “heart of darkness”. Dae-su’s thirst for revenge is so great that there is no depth he won’t sink to, including self-degradation and humiliation, to achieve it.

Park carefully distances his character from the stereotypical self-righteous cinema vigilante by making Dae-su aware that he has turned into a beast – the character frequently refers to himself as a monster as he devolves into a being whose new-found primitive emotions are put at the service of his thoroughly modern intelligence. An incredibly clever plot twist that makes the revenge theme a two-way game is startling, and the idea that we may cause others to suffer by committing seemingly trivial acts elevates the story above standard commercial entertainment.

Park, a former movie critic who taught himself filmmaking, says that the works of Greek tragedian Sophocles, particularly the Oedipus plays, informed his interpretation of the Oldboy story, and a brutal theme of incest does share a similarity with the ancient classic.

Oldboy brought the new Korean cinema wave to mainstream international attention, and the film picked up awards at numerous festivals, including the Grand Prix at Cannes. It’s known as part two of Park’s “vengeance trilogy”, which includes 2002’s Sympathy for Mr Vengeance and 2005’s Lady Vengeance.