Review | Mohammed Hanif’s Red Birds brims with anger at the absurdity, ugliness and human cost of war

- Pakistani writer’s third novel paints the familiar sight of a land bombed out of recognition, in a profoundly sad lament for innocent lives lost

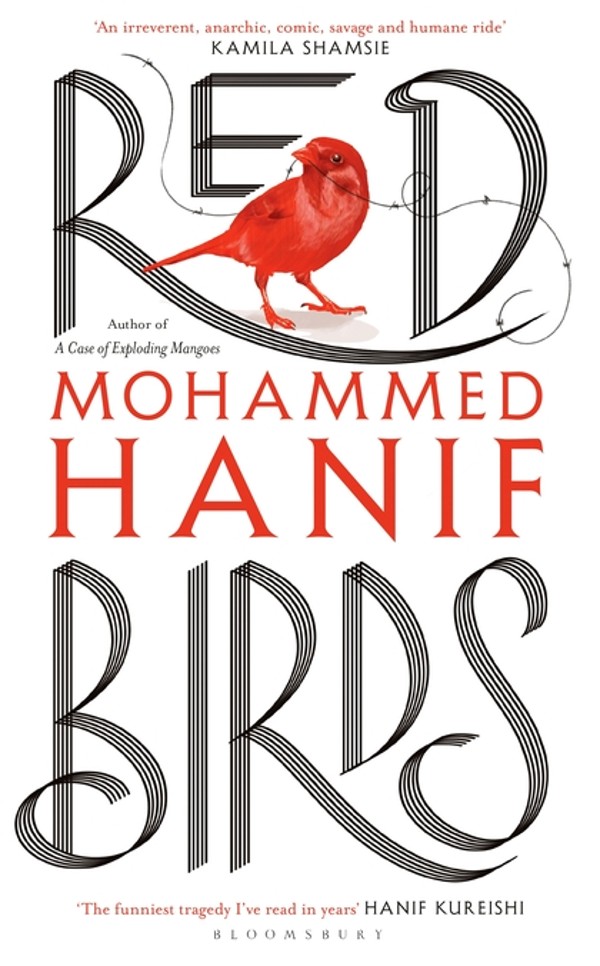

Red Birds

by Mohammed Hanif

Bloomsbury

For his third novel, Pakistani writer Mohammed Hanif has turned to the vast, arid landscape bombed relentlessly in the never-ending war on terror.

Novel retrieves forgotten memory of massacre in Pakistan

This land could be Pakistan or Afghanistan, carved out of desert-like nothingness and lying in an unruly fashion between the two political entities, with a boundary that those who live there neither recognise nor understand. The people, who all seem “Arab” to the clean-cut American pilots fighting the war on terror, survive on wile, instinct and luck, and a dog has the wisdom of a philosopher.

Hanif is a fine satirist. His first novel, A Case of Exploding Mangoes (2008), is a masterpiece that ridicules the pomposity of Islamabad’s armed forces and intelligence agencies, but also lets out a heartfelt cry for a more humane Pakistan, which began to disappear during the rule of General Mohammed Zia-ul-Haq (1978-1988).

His second novel, Our Lady of Alice Bhatti (2011), set in Karachi, shifts between the lives of the corrupt elite and the poor fighting for survival, and features an unlikely romance between a policeman who has had his thumb blown off and a Christian nurse.

The stench of temporariness pervades Red Birds – no clear lines are drawn and nothing is permanent: not townships, not maps, not landmarks – even homes are makeshift camps, where the letters “R” and “e” have fallen off a signboard, and the camp is named “fugee camp”. Life here is so hard that escaping to the desert seems like a good option. “God left this place a long time ago[…] He had had enough. I have had a bit more than that,” says Mutt, the dog.

The plot is incidental, since the dominant force is Hanif’s laconic world view, which emerges from the cynical observations of its three central characters: Mutt; Momo, a teenage refugee who wants to be a billionaire, inspired by hagiographies published in Fortune magazine; and an American pilot named Ellie, who is fighting his own demons and prefers a bombing raid in “Arab” lands to spending a weekend with his wife.

Pakistani miniatures artist gets the bigger picture

Ellie rationalises the bombings as acts of charity: “If I didn’t take out homes, who would provide shelter? If I didn’t obliterate cities, who would build refugee camps? Where would all the world’s empathy go?”

The pilot has crash-landed in this Nowhereistan and, to avoid the potential wrath of the refugees, he claims he was sent there to distribute food aid. Momo, meanwhile, is interviewed by an American woman, whom he calls Lady Flowerbody, who seems to be on a permanent gap year, moving from one developing country to another, taking copious notes to “understand” how the natives think, for a book that will interpret and understand the traumatised mind of an adolescent Muslim.

Momo is scathing in describing her: “First they bomb us from the skies, then they work hard to cure our stress [...] I am the Young Muslim Mind that will pay for her six-handed massages and her toned skin [...] I get PTSD, she gets per diem in US dollars,” he remarks. Momo’s mother, meanwhile, pines for his brother, Ali, who disappeared when visiting an abandoned American hangar. Is he dead? Has he been sold? Did he mislead the drones? Did the Taliban capture him? Momo’s mother observes: “First they bomb our house, then they take away my son, and now [they] are here to make us feel all right.”

When someone dies in a raid or a shooting or when someone’s throat is slit, their last drop of blood transforms into a tiny red bird and flies away

Ellie has been subjected to mind-numbing, out-of-date cultural-sensitivity courses concerning the people he bombs. Momo is so driven by the idea of being rich, that love, he decides, must wait until he has made his first million. He is embarrassed by his father’s servility to the Americans and grieves over his mother’s desperation about her missing son. And then there is Mutt, seemingly the wisest being in a land where dogs are considered unclean.

Hanif’s narrative rests on these three parallel stories, which eventually converge. Soaring over this scenario are the mythical red birds. They are real, Hanif writes. “The reason we don’t see them is because we don’t want to. Because if we see them, we’ll remember. When someone dies in a raid or a shooting or when someone’s throat is slit, their last drop of blood transforms into a tiny red bird and flies away. And then reappears when we are trying hard to forget them, when we think we have forgotten them, when we think we have learned to live without them, when we utter those stupid words that we have ‘moved on’.” The sky, Hanif says, is full of those red birds.

Hanif is angry about the war and what it has done to the innocent people bearing the brunt of the violence. Red Birds brims with an irreverent tone, always expressed in a deadpan manner, for which Hanif is rightly feted – but it is, ultimately, profoundly sad. The novel’s redeeming feature is the assured humanity of the nameless, forgotten victims of the war, caught beneath the bombardment.

The attacks are not new – British forces first bombed this region at least a century ago and, with the proliferation of drones, fighter pilots are becoming surplus to requirements. As Ellie notes: “They’re going to retire me and replace me with a geek in Houston who remote controls drones, someone who can fight a one-handed war while dipping his fries in barbecue sauce.”

The war is turning into a theatre of the absurd and such absurdities need a satirist such as Hanif.