Review | New Jackie Chan memoir Never Grow Up offers insights into a flawed everyman

- Martial arts action star recounts his days of high living as well as challenges of parenthood and breaking into Hollywood on his own terms

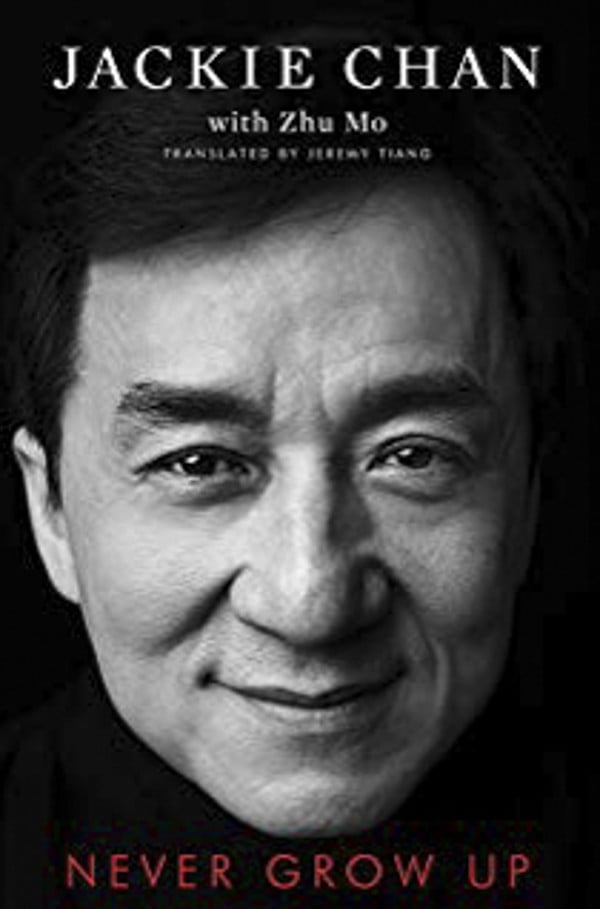

Never Grow Up

by Jackie Chan (with Zhu Mo; translated by Jeremy Tiang)

Gallery Books

Jackie Chan is arguably the best-known Chinese person on the planet and the only living movie star to straddle the East-West divide. He has risen from being a stuntman earning HK$5 a day to starring in blockbusters such as Rush Hour (1998), and become the world’s fifth highest-paid male actor on the 2018 Forbes list, taking home US$45.5 million.

The five most shocking revelations in Jackie Chan’s new memoir

Chan first told his story in the 1999 book I Am Jackie Chan, but which celebrity these days is content with just one memoir? Never Grow Up was first published in Chinese in 2015 and the English translation has just been published.

Apart from new insights into his film career, Never Grow Up reveals a darker side to Chan, with the actor writing of his visits to prostitutes and gambling dens, and of his struggles with alcohol.

Chan was born on April 7, 1954, in Hong Kong, weighing a hefty 5.4kg. The birth, not surprisingly, was difficult.

Like many in Hong Kong, his parents had arrived as refugees from the Chinese civil war. His father was a cook at the French consulate, where his mother worked as a maid. As a child of servants, young Jackie was bullied.

Chan’s energy earned him the nickname Cannonball, but his vitality exceeded his academic talents and he was held back after his first year in primary school. His parents then enrolled him at the China Drama Academy, in Lai Chi Kok, under the kung fu master Yu Jim-yuen. The boarding school enforced strict discipline and physical punishment for any infraction – a big change for such an unruly boy.

Given the emphasis on martial arts, however, Chan admits he received only a minimal formal education.

Jackie Chan is the fifth highest-paid actor in the world: Forbes

When Chan’s father was offered a job as chef at the American consulate in Australia, he accepted. His mother stayed in Hong Kong for two years, and then also moved. Chan was alone for eight years and he makes light of this, but the reader is left with no doubt that his childhood was a painful one.

Chan writes that, as a teenager, he and other students would hang around film studios begging for odd jobs, initially content with a HK$5 payment from the HK$65 Yu Jim-yuen received for each student, until the youngsters rebelled and received HK$35 a day.

He left the academy in 1971, aged 17, and worked in the Hong Kong film industry as a stuntman at a time when safety standards – and salaries – were scarce to non-existent. Chan writes that his big break came when a director wanted someone who could “vault a high balcony railing, fall with his back to the ground, flip in mid-air, and land steadily before continuing his fight” – all without boxes to break the fall, so it could be captured in one take. Chan volunteered and not only nailed the stunt but insisted on doing it a second time, to make it perfect.

He was then offered leading roles, but failed to make a splash as kung fu films at the time were dominated by the genre’s biggest star, Bruce Lee. After Lee’s death, in 1973, Chan signed to the Lo Wei Motion Picture Co, which had made Lee famous, but the studio wanted him only as a replica of the dead superstar.

In New Fist of Fury (1976), Chan played “a cold-blooded, rage-filled inhuman killer who sought revenge only”. The film flopped. Similar movies followed, all meeting the same fate. Chan writes that his name was “box-office poison”.

Finally, independent producer Ng See-yuen asked Chan what he wanted to do. His response showed how astutely Chan knew his strengths and what would work cinematically: “Bruce Lee would scream and roar while fighting in order to demonstrate his power and rage, but I prefer to cry out and pull faces. Bruce Lee is superhuman in the audience’s eyes, but I just want to be a regular guy. I want to play ordinary, flawed people who sometimes despair. They aren’t heroes; there are things they can’t do.”

I behaved so badly because of my deep insecurities. Ever since I was a little boy I’d been looked down on by rich kids

In 1978 and 79, Chan appeared in the films Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow, Drunken Master and The Fearless Hyena, and “seemingly overnight” became a hit. After making HK$3,000 a month plus HK$3,000 per film, Hong Kong film giant Golden Harvest swooped in and offered him HK$4.8 million per film. Chan had made it.

This initial flush of fame and wealth hit Chan hard: he “had a big chip on my shoulder” and took his anger out on shop staff, carried huge wads of cash, travelled with an entourage and drank so much that it affected his work.

Chan writes that he often drove drunk, even crashing two luxury cars in one day, and wasted money on gambling and prostitutes, in particular, one woman he knew only as “number nine”. He writes: “I behaved so badly because of my deep insecurities. Ever since I was a little boy I’d been looked down on by rich kids.”

Then America called. Chan made The Big Brawl (1980), which disappeared, and Cannonball Run (1981), in which he appeared as a nobody alongside Burt Reynolds and Sammy Davis Jnr. He returned to Hong Kong chastened, but then made one of his best-known films, Project A (1983), which features one of his most famous stunts: he climbs a flagpole, jumps onto a clock tower, and then falls face-down onto the ground – the fall broken only by two cloth awnings.

From here on, the pace of Never Grow Up quickens as the film roles come thick and fast. He refines a “Jackie Chan film” into a six-point formula: “Common men; improvisation; stunts!; starting with action; exotic setting, and positive values.” The formula is flexible enough to accommodate a huge range of stories while staying true to his style, allowing Chan to take the lead role in his own franchise.

The book moves into more personal areas. He briefly recounts courting his wife, Taiwanese actress Joan Lin Feng-jiao, spending more time on the difficulties of raising their son, Jaycee. He is upset when his child fails to show interest in his work, and he struggles with his son’s occasional recalcitrance, even once throwing the youngster across a room.

Jackie Chan’s daughter marries internet celebrity girlfriend

Having finally cracked Hollywood, Chan notes, proudly, that he succeeded on his own terms.

He recounts how his generosity was often taken advantage of, but says he would rather be occasionally fooled than be mistrustful. This openness and generosity is key to Chan’s character and is probably what has kept him popular over a 50-year career.

Never Grow Up captures the man in all his energy, bravery, fallibility, humour, resilience and warmth – warts and all.