What to read in 2019 – Haruki Murakami, Margaret Atwood and R.F. Kuang’s second novel

- Chinese authors set to delight wuxia and science-fiction fans

- Literary legends Haruki Murakami and Mark Haddon return while Yukiko Motoya makes her English-language debut

Last month I suggested 2018 was the literary year that never quite happened. Cancelled Nobels, underwhelming Rowlings, (still) no (new) Game of Thrones, the same-old-high-low debate surrounding the Man Booker, including a row about badly edited books.

The best books of 2018 – ones that made us laugh and cry

Other attempts have been made to introduce Jin’s vibrant mixture of martial arts, magic, history, romance and heroic quest to Western audiences, but Holmwood’s is the most concerted effort to date. A Bond Undone, the second part (of four volumes), is due out at the end of January. Translated this time by Gigi Chang, the novel picks up where part one left off, with our two antagonists, Guo Jing and “Ironheart” Yang Kang, learning uncomfortable truths about their fathers. If this isn’t enough, Guo is betrothed not once but twice, including to the daughter of Genghis Khan. Making matters worse is that neither is his true love, Lotus Huang.

From there Yip-Williams moved to America, settling in Los Angeles where a surgeon partially restored her sight. Still legally blind, she won a place at Harvard Law School, before starting a successful career. It is the honest descriptions of fighting for your life and tender messages to her family that make this book an inspiration.

January continues with a fine one-two short-story punch from a pair of excellent Japanese writers. Haruki Murakami celebrates his 70th birthday with the aptly titled Birthday Girl. On a rainy night in Tokyo a waitress celebrates her own (20th) birthday by delivering a meal to her reclusive boss. Any similarities between this enigmatic character and his enigmatic creator (who himself once ran a bar and restaurant) is purely accidental.

Picnic in the Storm is the debut English-language collection by Yukiko Motoya. Motoya may be unknown in the West, but this 39-year-old novelist and playwright has already won most of Japan’s prestigious literary garlands, including the Akutagawa and Mishima Yukio prizes. First published in Japanese in 2012, Picnic in the Storm (“Arashi no pikunikku”) won the equally elite Kenzaburo Oe Prize for its tales that topple everyday reality with strange twists: a woman takes up body-building and changes her life, unnoticed by her husband; a boy learns the secret to flying is held by an umbrella.

Other startlingly good books out in January include The Wall, by John Lanchester, who was raised in Hong Kong but lives in Britain. It’s not hard to trace the influence of both islands in The Wall, whose hero Kavanaugh patrols a 10,000 mile wall dividing the United Kingdom from “The Others”. An award-winning novelist and journalist, Lanchester mixes Brexit, Donald Trump, the rise of nationalism and environmental collapse in this unsettling cocktail.

Less disturbing, but no less readable, is Professor Chandra Follows His Bliss, the fourth novel by Rajeev Balasubramanyam, author of the excellent In Beautiful Disguises (2000). Our hero is an economist whose repeated failure to win the Nobel Prize drives him on the ultimate quest: to find the secret of happiness. Chandra has plenty of questions to ask, about love, fatherhood and health, not least after being knocked off his bicycle.

Amazingly, January is still not done: the month ends with Adèle, the second English-language novel by Leïla Slimani, who in 2016 caused a global splash with Lullaby. Slimani has shifted her attention from murderous nannies to sex addiction. If this is all too much, Kwoklyn Wan’s Chinese Takeaway Cookbook might ease your troubles.

Duojizhuoga’s Love in No Man’s Land follows seven-year-old Gongzha, whose way of life in Tibet’s remote Changthang Plateau comes under threat when the Cultural Revolution sweeps outwards from China. When Gongzha helps to hide treasures belonging to a nearby monastery from officials, his actions have ramifications that take decades to play out. Also noteworthy is Yangsze Choo’s The Night Tiger, a magical love story set in 1930s Malaysia which echoes an ancient Chinese tale about men turning into tigers.

Fans of TV drama Killing Eve and Quentin Tarantino’s True Romance will enjoy Un-su Kim’s The Plotters, in which an assassin takes pity on his quarry and allows her to choose her means of death, only to find that he might just have become a target himself.

Other big-name writers returning in 2019 include Margaret Atwood, who ensured a happy end to 2018 by announcing the sequel to her 1985 masterpiece, The Handmaid’s Tale. Set 15 years after the uncertain conclusion of that novel, The Testaments (due out in September) again stars her heroine, Offred – though whether she is facing death, prison or freedom remains to be seen.

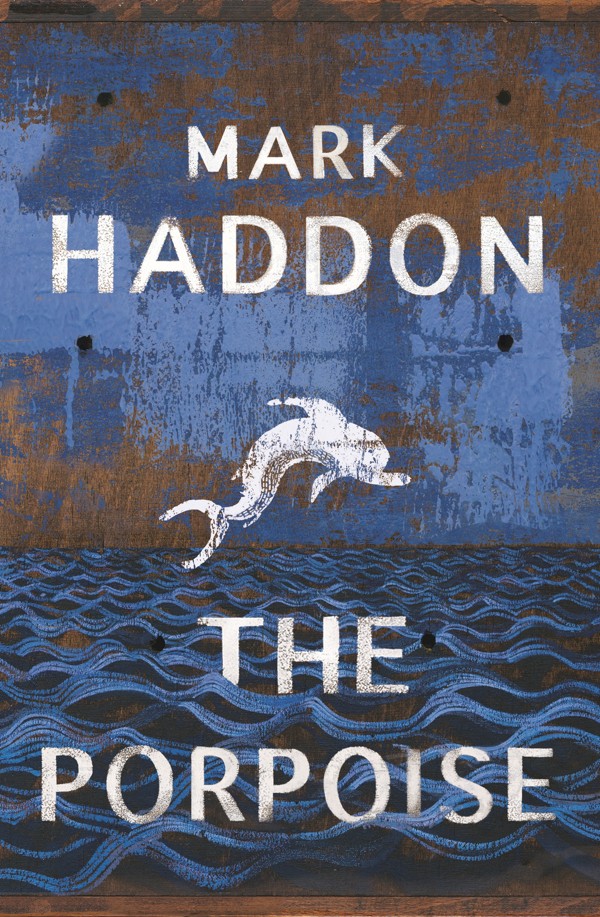

In another long-awaited return, Mark “Curious Incident” Haddon publishes his first novel for seven years. Inspired by the ancient story of Pericles, The Porpoise revolves around a baby girl who is the sole survivor of a plane crash. Years later she meets a strange man who seems to know her story better than she does.

In April, Ian McEwan showers us with Machines Like Me, his take on artificial intelligence. McEwan being McEwan, this is infused with the erotic: our hero buys a synthetic human to fondle, converse with and, dare we say it, love. Something eerily similar goes on in Jeanette Winterson’s new novel Frankissstein, in which gender, sexuality and technology all hold hands in this update of Mary Shelley’s seminal gothic horror.

One wonders which books published this year will still be talked about in 2219? Perhaps the science dreamed up by Liu Cixin, Ian McEwan and Jeanette Winterson will help us find out.