Review | The Kinship of Secrets – the true tale of sisters separated by the Korean war inspires a powerful novel

- Eugenia Kim again mines her own family’s history for her latest novel

- Shifting the story between the United States and South Korea illustrates the power of separation and the duty of sacrifice

The Kinship of Secrets

by Eugenia Kim

Bloomsbury

In a poignant afterword to The Kinship of Secrets, Korean-American author Eugenia Kim describes the Korean war as having been not only the fifth deadliest conflict in human history, but also “the forgotten war”.

Asian-American’s debut novel depicts Chinese sisters’ solidarity

In this gentle historical saga, her second to date, Kim opens a window onto the conflict through the story of a Korean family torn apart by war but brought together by love, and by secrets dating back to the Japanese occupation.

Told through the alternating perspectives of two sisters, Inja and Miran, and inspired by the story of her own family, Kim’s narrative spans two continents and more than two decades. It opens in a residential enclave of Seoul, with the sounds of a weary newsmonger broadcasting the headlines of the day to the still sleeping residents.

It is 1950, the year of the invasion by North Korea. The man is talking of a retreat by the North Korean People’s Army and how president Syngman Rhee is urging the people of Korea to “trust our military without being unsettled in the least, to carry on with their daily work and support military operations”.

But “invasion”, like the word “communist”, is not a concept understood by three-year-old Inja, who is woken by the newsmonger’s pronouncements. Slipping out of the bed she shares with Halmeoni, her grandmother, she peeks out of the door to ask her uncle about what the newsmonger is saying. Having heard her uncle and aunt argue the previous day about whether to leave their home and head south, she realises this invasion could lead to an exciting change of routine. She assures her uncle that she can not only pack by herself but also help Halmeoni, who needs a cane to stand.

Kim excels in her portrayal of Inja, invoking the little girl’s sense of wonder at the sounds, sights and sensations of the world around her with such skill and immediacy that the reader is practically transported back to pre-war Seoul. Indeed, Kim’s first chapter alone – which ends with the newsmonger going home to soak his feet after his editor chooses not to alarm the public with confusing new reports of battle losses and the rumour that Rhee has fled Seoul – contains all the power and masterful completeness of a well constructed short story.

Kim’s storytelling prowess is no secret among her many fans. Long before the Washington-based author won accolades and devotees with her debut novel, The Calligrapher’s Daughter (2009), she was known for her short stories and essays. Based on years of painstaking research into Korean history, The Calligrapher’s Daughter told her mother’s story against the backdrop of the Japanese occupation of Korea, won several awards and made the shortlist of the 2010 Dayton Literary Peace Prize.

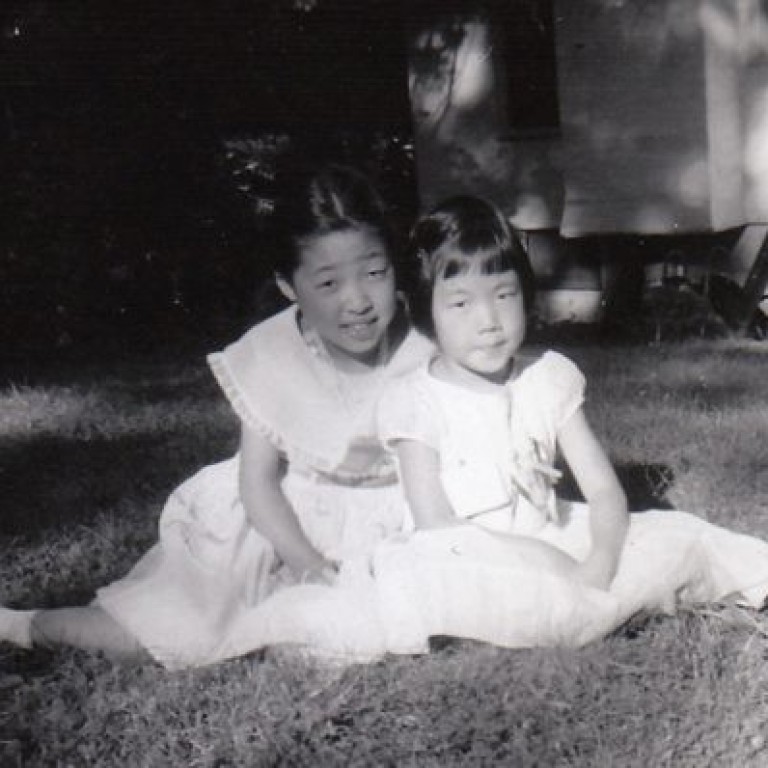

The Kinship of Secrets is inspired by her sister, Sun, and mirrors many other elements of her family’s story. While a work of fiction, “much essence of true story remains, including the story about why Sun was left behind”, Kim states on her website.

Kim’s real-life sister was one year old when her parents left with relatives and emigrated to the United States in 1948. War and US immigration laws kept them separated for the next decade. Kim’s fictional creation, Inja, was left behind in Korea with her maternal grandparents, uncle and aunt as a baby.

Early on in The Kinship of Secrets we learn that this was a kind of guarantee that her parents would soon return to Korea from America, where they had migrated to out of fear that her father, who worked for the Americans, would be kidnapped or assassinated by the North Koreans. But Inja has no memory of her elder sister, Miran, or her parents, although she does have photos of them. While she views them as “ghost people”, she still plans to take items they’ve sent her in packages from America if her grandfather decides to flee.

These packages – invariably itemised – are a powerful motif, and have a different meaning for Miran, who helps her mother, Najin, wrap them once a month. As the “trouble in Korea” progresses, they wrap packages two or three times a week, not that Miran understands what kind of trouble Korean could be in. She is more worried that the Russians might drop atomic bombs on the US.

Miran is jealous of her sister, imagining Inja unwrapping the brightly coloured gifts and old toys packed inside the cartons going to Korea, which she and Najin wheel to the post office. There she acts as a go-between at the mailman’s window, her mother not having learned English – unlike her father, who works as a translator and broadcaster at Voice of America in addition to his pastoral duties at a Korean church.

As Inja’s world springs vividly to life, so, too, does the Cho family’s existence in suburban America through the eyes of Miran. She illuminates her parent’s anxieties and in particular her mother’s pain and guilt at leaving a daughter behind, along with the ongoing costs and complexities of uprooting lives from one country to another.

Kim occasionally switches to the voice of Najin, but maintains the two sisters’ individual perspectives throughout the duration of the war, and afterwards through the ongoing tensions between North and South and the political turbulence and student unrest in Seoul. The horrors of war, death and displacement hang like ghostly shadows at the edges of the book, often entering in poignant and ingenious ways. One of the joys – and triumphs – of this novel is that even as the sisters grow older and are reunited, Kim maintains a palpable sense of wonder and beauty in her narrative.

And as its title suggests, secrets haunt the book in unexpected ways. Secrets are shared and secrets are kept, with some only glimpsed, their depth and power becoming apparent only late in the novel. Near the start, for example, we learn that Inja has to bathe Halmeoni’s feet every night. She hates the job, because her tiny, wrinkled grandmother has no nails left on her toes. But the enormous sacrifice made by Halmeoni that caused this condition isn’t revealed until later in the narrative. When Inja is finally told, she is sworn to secrecy.

Another potent secret lies at the heart of the book, serving as a powerful meditation on love, sacrifice and the nature of hidden truths, sensitively blurring the line between all three.

There’s a freshness in Kim’s uncontrived, unhurried storytelling. She succeeds in not only opening a window onto Korea’s forgotten history and the resilience of its still divided people, but prising open the door to the deepest recesses of the human heart.