Inside a South African interior designer’s dream home - sustainable living in the Indonesian jungle

Jennifer Newton has created an environmentally friendly jungle idyll in Lombok – ‘I wanted to grow my own food, be self-sufficient and explore if it was possible to live without consuming’

Jennifer Newton’s extensive imprint on Hong Kong homes runs the gamut from rustic glam to modern industrial, all with an appealing eco-conscious patina. But the interior designer was never entirely satisfied with her impact, despite the accolades she received. Media coverage – including by Post Magazine – praised the environmentally friendly and natural materials that went into many of her projects, she says, but frustration grew because that seemed as far as she could go.

“I wanted to do something that was really natural,” Newton says, from south Lombok, Indonesia. “I wanted to grow my own food, be self-sufficient and explore if it was possible to live without consuming.”

Inside a German art activist’s ‘zero waste’ Bali villa

That meant adopting a way of life not even her new neighbours on the Indonesian island were entirely used to. South Africa-born Newton, who grew up in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) and went to school in England, lived in Hong Kong for three years from 2006, after which she decamped to Sydney, Australia. In 2012, she moved to Bali, and Lombok followed two years later.

Mawun Mud Village, the mountain-ringed jungle idyll she created for herself, is the culmination of learning and experimenting with what her website describes as “holistic living and ecologically regenerative design and construction”. Four years since moving to the island, she now hopes to hand to another dream catcher all that she has built.

In addition to a dormitory and two bungalows (one still to be completed) are a couple of dwellings fashioned after traditional Indonesian rice barns, one of which she occupies. In her hilltop home, the living space, with hammock and floor cushions, is on the first level; the bedroom beneath a thatched roof; and the kitchen and dining area on the generous mud-plastered ground level.

‘Focus architecture on natural habitat, not monetary value’

Many materials have been salvaged, including the exposed beams, from old Lombok houses, and wood from abandoned boats, which she used to make furniture.

“I’ve been designing my dream house for an eternity, but this was totally ad hoc,” Newton says, with a laugh. “It was supposed to be a little room that I would have temporarily while the rest of the place was built, but it turned into my house.”

It set the course for development of the idyllic acre of land that she hopes will become a retreat with an educational message.

“At the start I couldn’t speak the language and so it was easier to ask the builders to build what they were familiar with,” Newton says. Then she progressed to making mud bricks and designing structures to be built with them, including her bathroom, a rudimentary curved outhouse that is the epitome of shabby chic. Her builders, initially flummoxed by her seemingly outdated choice of material, came to understand the “concept” when they recognised she was simply building in the style of Lombokians a century ago, she says.

The environment, people and profit are equally important in guiding any design [...] You’re not just ripping out trees because there are ecosystems beneath our soil. When we go in with excavators we’re destroying that

They probably had a moment similar to Newton’s “Let’s do this!” when she saw the potential of the plot. “This” was to put into practice all she had learned about mud-brick building (at Gaia Ashram, near Nong Khai, in northeastern Thailand) several years earlier. She was also keen to live according to the values of permaculture, a portmanteau coined by Australian Bill Mollison from “permanent agriculture and permanent culture”.

“The environment, people and profit are equally important in guiding any design,” Newton says. “One principle is conservation – you serve the site. You’re not just ripping out trees because there are ecosystems beneath our soil. When we go in with excavators we’re destroying that.”

Developing Mawun, which is named after a beach nearby, went hand in hand with increasing the biodiversity of the land, she says, adding that like-minded foreigners on the island are now building using similar techniques.

Her team of builders, including volunteers, worked mainly with the materials at hand, although concrete was brought in for the foundations and steps that lead up inclines and connect the buildings. Jungle rope (vines) tied things together “although we did use nails on occasion”, she says.

Putting bamboo, stone and wood back into Chinese architecture

Importantly, there is no such thing as waste, in nature and permaculture, Newton stresses, pointing to her biocomposting toilet.

“It’s not very glamorous but it’s really important from an ecological perspective,” she says. “Here it all goes into a pit and you put rice husk on top. You use that pit for six months or until it’s full, then you move the toilet. It doesn’t smell at all.” After having been left to sit for a year, the waste is used as fertiliser.

Although Newton acknowledges that sewerage regulations are different around the world, she argues: “There’s no reason why you couldn’t find a way of using a [commercially available] biocomposting toilet in Hong Kong. Once you start thinking in this way, you can become creative and come up with solutions.”

Not that there are always quick fixes, or even a set path. Having begun the project with a partner, she says it was daunting to see it through on her own when they went their separate ways.

Now dig this: a new crop of organic farms and workshops

Newton also had to deal with cultural differences. Her first security guard, she remembers, couldn’t get his head around the concept of ownership, and strangers would help themselves to everything from light bulbs to tomatoes.

“I left my shoes at the bottom of my house once and I saw him wearing them the next day,” she says with mock shock. “But I have a different security guard now and they know, ‘We don’t go in there and steal stuff.’

“It’s been such a journey.”

Living area The open-sided first-floor living area, featuring beams from old Lombok houses and bamboo overhangs, is furnished with a hammock (US$90) and floor cushions (US$70 each) from Vivi Natural. The pot in the foreground came from a street stall in Penujak village, Lombok. The mat was handmade locally.

Bathroom The mud-plastered curved wall hides Newton’s bathroom, just outside her house. The baskets (about US$50 for the set) came from Jogja Stool.

Bathroom The basin (US$90), sitting on a mud-brick block in Newton’s open-air bathroom, came from Puspa Stone & Wood (Jalan Raya Mas, Ubud, tel: 62 817 9704 645). The mirror (US$50) was from another shop in Ubud.

Rice-barn house The first building to go up in Mawun Mud Village was a traditional rice barn, which became Newton’s home.

Villa Cashew Mud brick was used to build not only the walls of this guest bungalow but also the bed base, which features lime plaster, also used on the floor. The baskets came from Jogja Stool and the mosquito net from Vivi Natural.

Dormitory Among the handful of buildings that make up Mawun Mud Village is a dormitory, which comes with a large hang-out area.

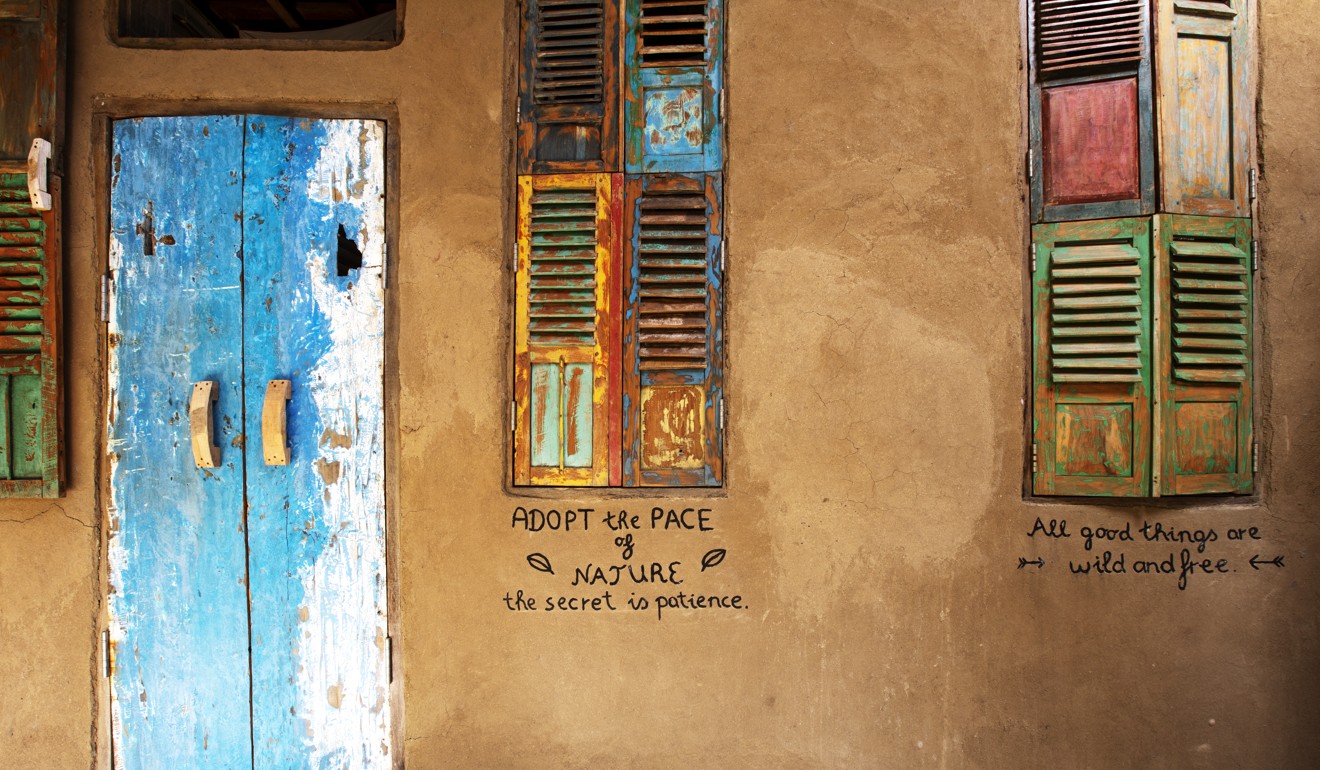

Dormitory Twelve beds in three conjoining rooms make up the dormitory, which features windows reclaimed from old houses in East Lombok and doors made from old boats.

Tried + tested

Bricks in the wall Mud plaster (left) covers the mud bricks used to build Jennifer Newton’s bathroom walls. The brick-building process is relatively simple, says Newton, and begins with soil and a good mix of clay and sand. To that, add water until it turns to mud, and rice husk (which reduces cracking). Then place in a wooden mould and leave to dry in the sun for about a week in the tropics, longer if in a cooler climate.

“Soil naturally contains both clay and sand so after a while you learn the right ‘feel’ of the mix, although it’s not a precise science,” says Newton. “If it’s too sandy, you add clay, and if it’s too claylike, you add sand.”

Newton says the lifespan of mud brick is potentially thousands of years, adding, “The Great Wall of China is in part mud.”