How Bruce Lee made Lee Kung Man’s everyday undershirt a fashion icon

The stubbornly small Hong Kong manufacturer does not like collaborations, expansion ... or interviews with the press

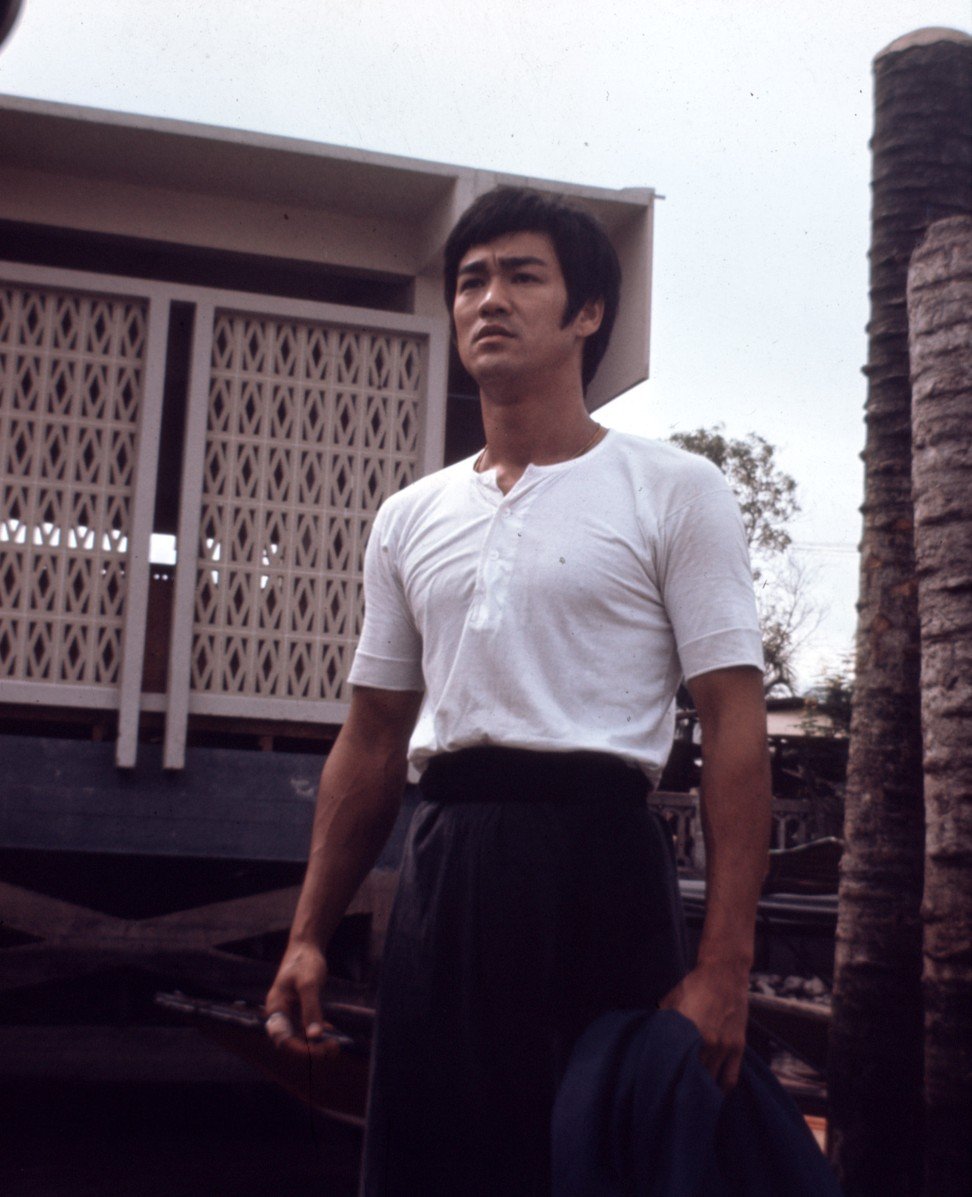

Bruce Lee dressed in a white, round-necked T-shirt with three buttons at the front. It’s an iconic image from the 1970s, thanks to which that humble, lightweight undershirt became famous around the world. Few international fans knew it, but that sought-after cotton garment was made in Hong Kong – and still is.

Lee Kung Man, the media-shy company behind the shirt, was founded in Canton – modern-day Guangzhou – in 1923. In Hong Kong, the firm has been manufacturing that simple but signature product at its Lai Chi Kok factory for decades, selling it in the same packaging and from the same shops – in Sheung Wan, Wan Chai, Sham Shui Po and Mong Kok.

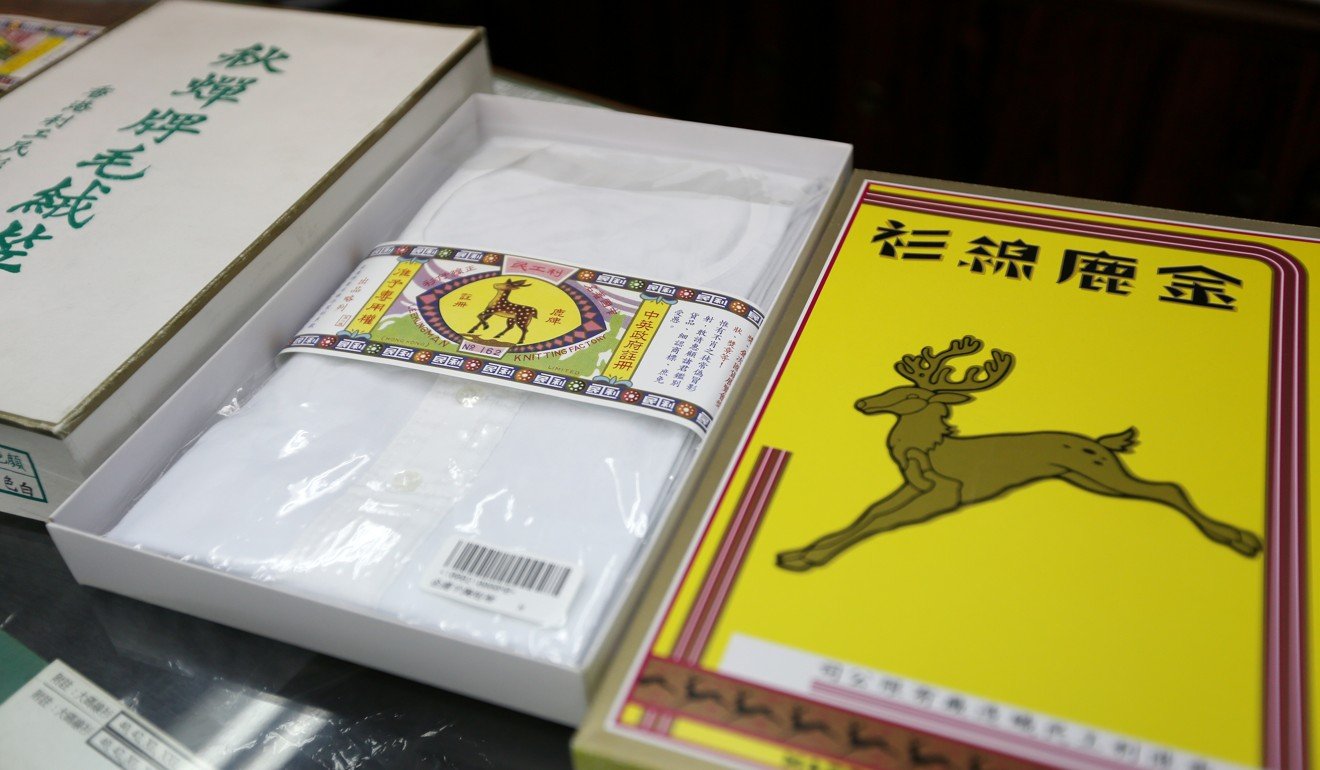

Entering a Lee Kung Man store is like going back in time, with the products in cardboard boxes, stacked behind the counter. Customers have to ask to see the merchandise and cannot try anything on. When it comes to the summery undershirt as worn by Lee, the choices are white, white or white, with short, long or no sleeves.

Prices start at HK$45 and rise to HK$270. Not cheap, but roll the fabric between your fingers and you will discover that it is extremely thin yet durable. This quality – coupled with the fact that Lee Kung Man has been doing its thing the same way for almost a century – is what Douglas Young, co-founder of Hong Kong lifestyle label G.O.D. (Goods of Desire), loves about the brand.

“I wear their T-shirts all the time. They are so thin,” he says, describing the fabric used for the garments as “mercerised cotton”, which is produced by treating raw cotton with caustic soda, making it shrink, become more hard-wearing and gain a silk-like texture. “The material is super absorbent so that when you sweat, it evaporates just like that. It’s better than those hi-tech fabrics from Nike. The synthetic fabric is not as good as this cotton.”

In a television advertisement from 1974, an older man, though bundled up against the cold, is shivering while a young man in a Lee Kung Man undershirt appears perfectly comfortable. “They are known as undergarments; no one wore them ‘out’ – you didn’t see people wearing them,” Young says. “But Bruce Lee made it OK to wear it as a top.”

G.O.D. liberally plunders Hong Kong’s past for the dynamic designs it applies to its apparel and homeware, so it comes as no surprise to discover that Young admires the Lee Kung Man shirt’s retro packaging. The yellow box features an illustration of a prancing Golden Deer, the garment’s brand mark, and the all-important declaration, “Made in Hong Kong”, below.

“Normally, you have to buy three items before they will put them in a box,” Young says, “but I love the boxes so much that I buy three shirts and ask to have them put into three separate boxes.”

Some years ago, G.O.D. attempted to collaborate with Lee Kung Man. “We had to beg them to do the collaboration, and the people at Lee Kung Man are very stubborn,” Young says. “We wanted to take the existing material they use and make it more contemporary looking, but they refused to manufacture the clothing according to our design. In the end, we had to take their finished product and then get someone else to do the modification.”

Alan See, co-founder of bespoke Hong Kong tailoring and accessories retailer The Armoury, also attempted to collaborate with Lee Kung Man. “I tried to work with them and they had no email, so I had to fax everything to their friend’s place,” says the Malaysian-born See, who occasionally wears Lee Kung Man cotton T-shirts, considering them good for layering. “Then they got the fax and we communicated like this, back and forth. It took so long to do things.”

See says that what makes Lee Kung Man undershirts so comfortable is their tube-knit design, which means no side seams. “The machines [on which they are made] are almost obsolete,” he adds, “so they have to cannibalise other machines to repair them.”

Lee Kung Man founder Fung Sau-yu was born in 1889 in Shun Tak (today the Shunde district of Foshan city, Guangdong province), and made his living as a young man selling Western goods in Canton. In 1923, he bought six hand-operated hosiery-making machines, giving his new company a name that means literally “benefiting workers and farmers”.

Using wool imported from Britain, Lee Kung Man quickly gained a reputation for quality and, by 1925, the firm boasted 20 machines. A few years later, Fung added singlets to the product line and opened a factory on Hong Kong’s Des Voeux Road Central.

When Japanese troops invaded Canton in 1938, the Lee Kung Man factory there was destroyed, so Fung moved his operations to Shun Tak, and then, in 1940, he left for Hong Kong. The next year, however, with the Japanese occupation, Fung suspended operations, devoting his time to serving the Taoist temple Fung Ying Seen Koon, in Fanling.

With the war’s end in 1945, Fung returned to Canton and restarted manufacturing, enjoying brisk sales before the 1949 Communist assumption of power in China. With his mainland operation nationalised, Fung again fled to Hong Kong, spending the rest of his days in Fanling, delegating to his sons and nephews. He died in 1952.

When Post Magazine calls Lee Kung Man’s head office, in Wan Chai, to request an interview with the owners, the person who answers does so brusquely, in the negative, and puts the phone down, suggesting the company has no need or desire for media attention. Business, one assumes, must be good.

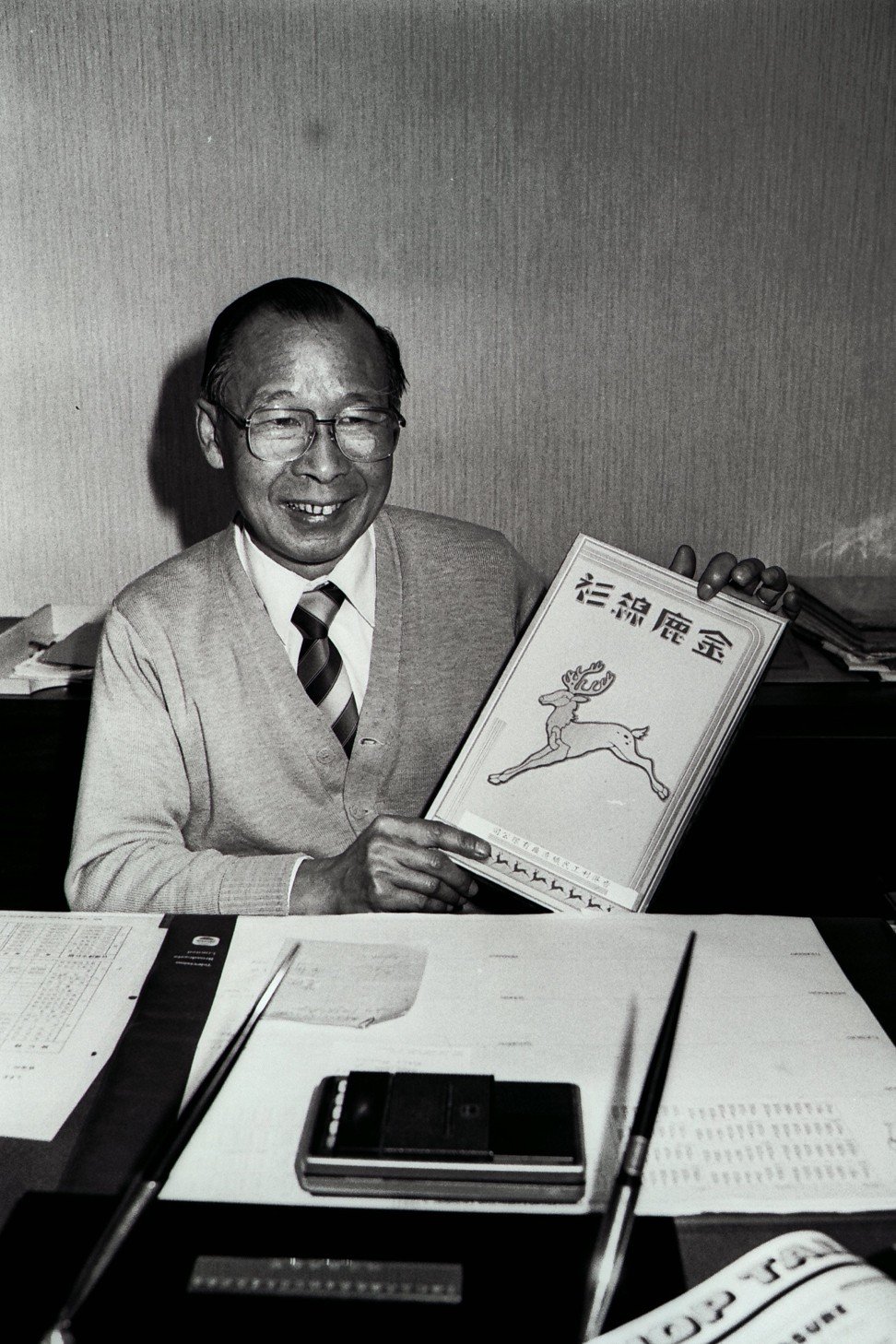

In 1985, however, a reporter from the South China Morning Post did manage to interview Fung Ka-cheung, son of Fung Sau-yu, when Golden Deer undershirts cost HK$54.

Back then, the company produced thousands of items a year (“And Mr Fung expects that they always will”), and the managing director said quality remained the priority, the shirts made using 100 per cent natural cotton sourced from Switzerland and Britain, and boasting a fine count of 100 threads per square inch compared with the coarse 24-count fabric used in many competing products.

“My father saw some expensive French garments in the 1920s, and he decided we could do the same thing here,” Fung, who has since passed away, told the reporter. “The style and cutting of the clothes is basically the same as it was then. But now undershirts with a lot of buttons are not so popular, because they are inconvenient. We still sell some, though.

“If you change to more modern styles, the changes have to come too quickly. The next day people may not like it, so you have to change every year.”

Fung added that although the company had received many requests to send undershirts to the United States and Europe, mail order sales and foreign sales tax regulations were “too complicated”.

“We are producing for the local market,” Fung told the Post, adding that 80 per cent of the company’s products were sold to customers in Hong Kong, with 20 per cent finding their way overseas through agents.

“The scale of our business is limited,” Fung added. “Our Hong Kong factory cannot cope with export business. We would have to hire more people and expand our facilities.”

And as it was then, so it seems to be today, with Lee Kung Man appearing to have no interest in changing its time-tested approach. The customer base, however, may be changing in subtle ways.

At Lee Kung Man’s Wan Chai shop, on Johnston Road, a sales assistant says that many young people are buying the company’s clothing these days, but she is unsure why.

And thanks to style influencers like Young and See, as well as Bruce Lee fans, Lee Kung Man is being discovered by consumers beyond Hong Kong.

Young ranks Lee Kung Man alongside Levi’s, Harley-Davidson, Adidas and other international brands with strong heritage value. “The Japanese really appreciate vintage stuff,” he says. “Evisu bought old Levi’s machines and they did really well making vintage jeans, and now Levi’s regrets selling the old machines.”

He recalls a Japanese consortium trying to buy out Lee Kung Man, but being turned down.

See agrees on the Japanese appreciation for all things old-school. “It’s like seeing the guy who works on pottery, or makes knives. There’s always been a culture of appreciating craftsmanship,” See says.

“The new tailors these days are Japanese because they know how to appreciate it.” Using a Japanese word for people with obsessive interests, he adds, “It’s that otaku mindset.”

One thing is certain: even in the 21st century, Lee Kung Man’s shirts refuse to go out of fashion. Look up #leekungman on Instagram and you will find almost 200 posts by fans – pictures of the packaging, of the shop, of enthusiasts wearing the iconic undershirt, perhaps with a sharp Italian blazer. Many reference Bruce Lee.

When The Armoury was attempting to collaborate with Lee Kung Man, See was lucky enough to meet the current owner (whom he doesn’t name; when Post Magazine rings back to ask for the owner’s identity, the company refuses to divulge the information).

“He’s a factory guy, very boisterous,” See says. “He’s comfortable in that he owns his own stores. He has no push to change.”

Which makes Lee Kung Man all the more alluring in this age of fast fashion.

“We’ve been in Hong Kong since 1930 and we’ve built up a very good reputation here,” Fung Ka-cheung told the Post in 1985. “In all these years, some other companies have closed down. Maybe their quality was not so good or their management was poor. Our success depends on the trust of the public.”