From belle époque Shanghai to occupied Hong Kong, the literati who broke down cultural barriers

T’ien Hsia magazine set out to be a platform for cross-cultural exchange until war intervened; managing it was this correspondent’s mother, who fled to Hong Kong, where she bought opium for Emily Hahn, and almost became personal aide to Madame Chiang

A photograph in our family album captures an extraordinary scene at Hong Kong’s Repulse Bay in 1939. People in the British colony at that time were acutely aware of social and racial distinctions, and yet the beach party in the picture has Chinese, Eurasians and Westerners – most of them in swimwear – all relaxing together.

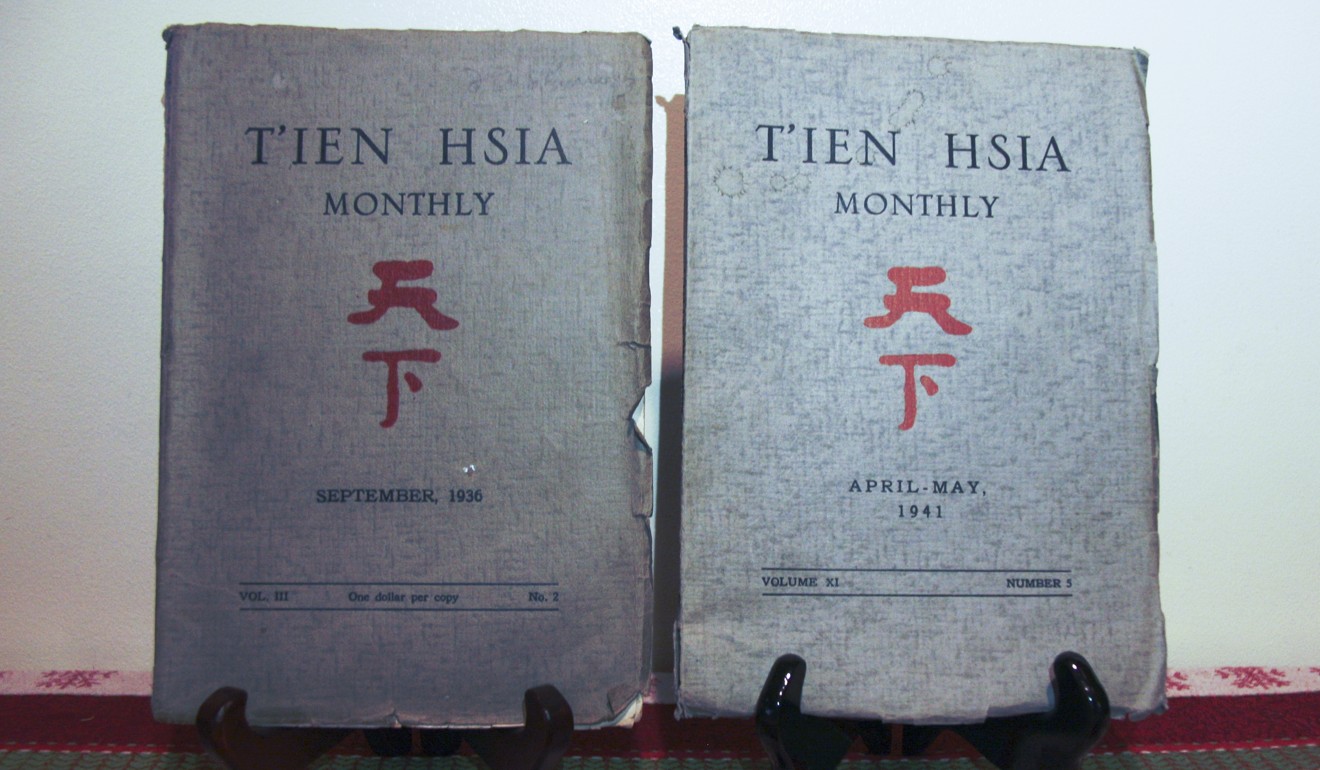

The multiracial gathering consisted mostly of displaced Shanghailanders – writers and staff of cultural magazine T’ien Hsia Monthly, which launched in Shanghai in 1935 and moved to Hong Kong after the Sino-Japanese war broke out in 1937. T’ien Hsia, which translates as “everything under heaven”, was distinctive in being a Chinese-edited, English-language publication aimed at an international readership. It began at the height of an era of unprecedented openness in China, with the goal of promoting international cooperation through cultural ties.

Seated second from right is T’ien Hsia’s “backroom girl”, Louise Mary Newman, who was involved in every aspect of the magazine, from its inaugural issue until its abrupt closure in dramatic circumstances. Newman, who would marry Arthur “Paddy” Gill, the Irishman sitting next to her, became my mother after the war.

Her suspicion deepened when a servant opened the door of a second-floor flat to reveal four rooms, almost bare. A bespectacled Chinese man in a dark, three-piece suit appeared. Speaking rather shrilly, with an educated English accent, he introduced himself as Wen, and he would head up the soon-to-be-launched magazine. The publication, he explained, would feature Chinese scholars explaining their country to the world, and Western writers expressing their views on China.

The T’ien Hsia office was like a teahouse where contributors dropped by for a brew, to chew watermelon seeds and to have a chit-chat. They were known for their liberal lifestyles as well as their progressive thinking

Newman was only slightly reassured when Wen told her the magazine was backed by the Sun Yat-sen Institute for the Advancement of Culture and Education, headed by Sun Fo, president of the Legislative Yuan (the legislature during the republican period in China) and son of Sun Yat-sen, leader of the 1911 revolution that had replaced the imperial Qing dynasty with a republican system.

Wen tested Newman by dictating a poem, which she had to take down in shorthand and type up. He read aloud A Shropshire Lad (1896), by English poet A.E. Housman.

After scrutinising Newman’s work, Wen said she was the only one out of more than 50 applicants who had reproduced the poem without error. He offered her double what she had been earning at Reuters. Nonetheless, Newman’s mother fretted that she would be leaving a well-established organisation for an untried enterprise.

Newman, however, took the plunge, unaware of the misadventures, upheavals and enduring relationships that would follow.

After working for Western journalists who produced stories with a premium on accuracy and speed, Newman now entered the cosmopolitan world of Shanghai’s literati. T’ien Hsia’s early masthead included esteemed scholars of the day. They represented the cream of the tens of thousands of students who travelled abroad during the republican era and returned to contribute to China’s artistic belle époque.

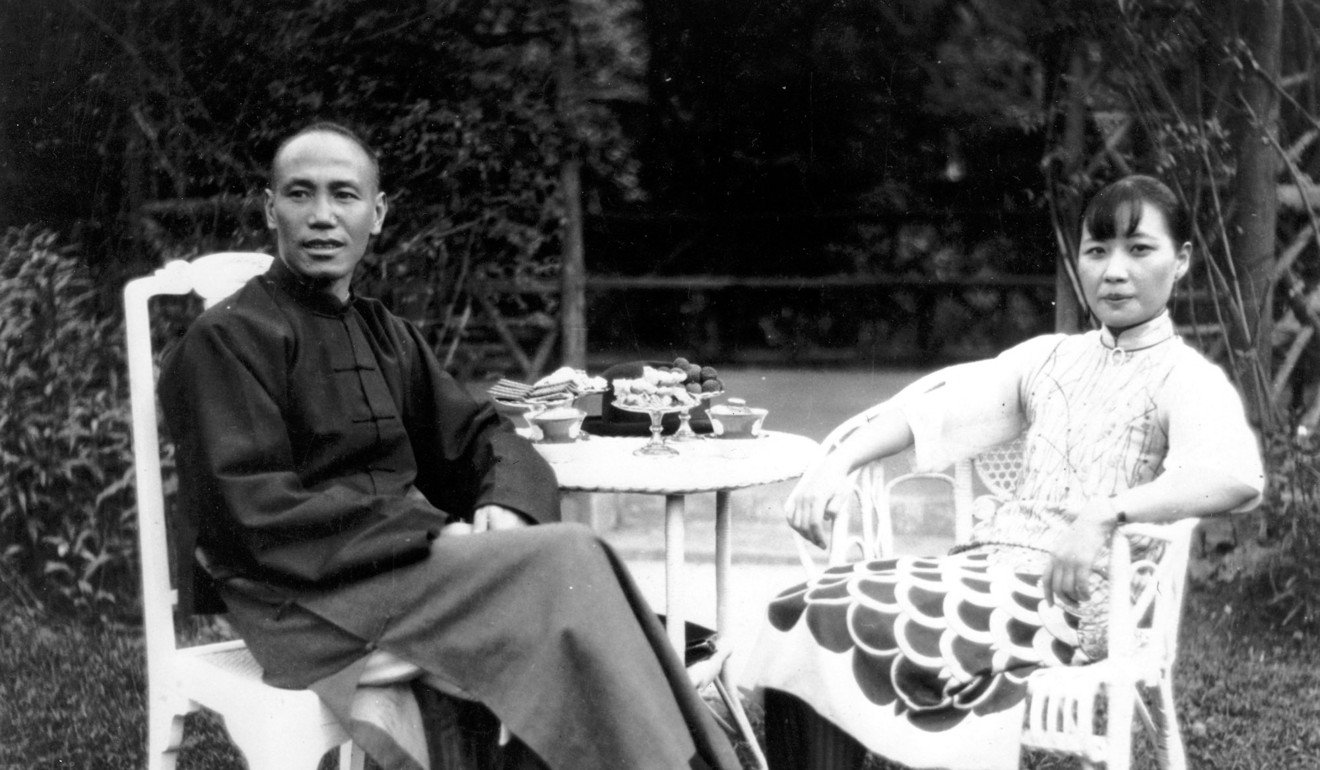

Wen, a professor of English language and literature at Peking University, was from a well-off Chinese family living in the Dutch East Indies and Singapore, and he had been educated in the Lion City and at Britain’s Cambridge University, where he had caused a stir by bringing his own manservant.

He was an avid Anglophile who dressed in English suits and loved to hobnob with British diplomats and literary figures visiting Shanghai.

Then there was Wu Ching-hsiung (John C.H. Wu), a brilliant lawyer who had studied at the University of Michigan Law School, in the United States, where he had become close to the renowned jurist Oliver Wendell Holmes.

Wu wore Chinese gowns and deliberately spoke English with the accent of his hometown, Ningpo (modern-day Ningbo), in Zhejiang province. A self-confessed former playboy, Wu had joined the Legislative Yuan, where Sun Fo asked him to draft China’s constitution in 1933. He was also in the process of converting and would become a devout Catholic.

Rounding off the masthead was Chuan, an alumnus of the University of Illinois, in Chicago, who taught philosophy at Tsinghua University. Known as T.K., he was a bachelor devoted to his sister Mei-Mei and an Annamese cat. Newman recalled that it took little for highly strung T.K. to burst into tears.

Aside from setting up and running the office, Newman’s responsibilities at the magazine included editing, liaising with the printer, Kelly & Walsh (established in Shanghai in 1876), and proofreading.

In ambience, the T’ien Hsia office was like a teahouse where contributors dropped by for a brew, to chew watermelon seeds and to have a chit-chat. They were known for their liberal lifestyles as well as their progressive thinking.

China embraced modernity with relish and was a truly open society that was rapidly diversifying at every level. English was spoken to a widespread degree, even in the countryside

One regular was Shao, a famously beautiful man with expressive brown eyes and sensuous, pouting lips framed by an oval face. He favoured silk gowns and brightly coloured capes. From a rich family, Shao was known for his literary talent and his dissolute lifestyle, which included an addiction to opium.

Another visiting contributor was William Empson, the English poet and critic who taught at Chinese universities after being expelled from Cambridge for being caught in flagrante delicto with a female companion.

Harold Acton, a British writer who studied Chinese language, traditional drama and poetry, paid a visit that was memorable for Newman. The T’ien Hsia staff took Acton out in a car in which space was so cramped that she had to sit on his knee in the back. She had little to worry about, though, as Acton was thought to have a predilection for boys.

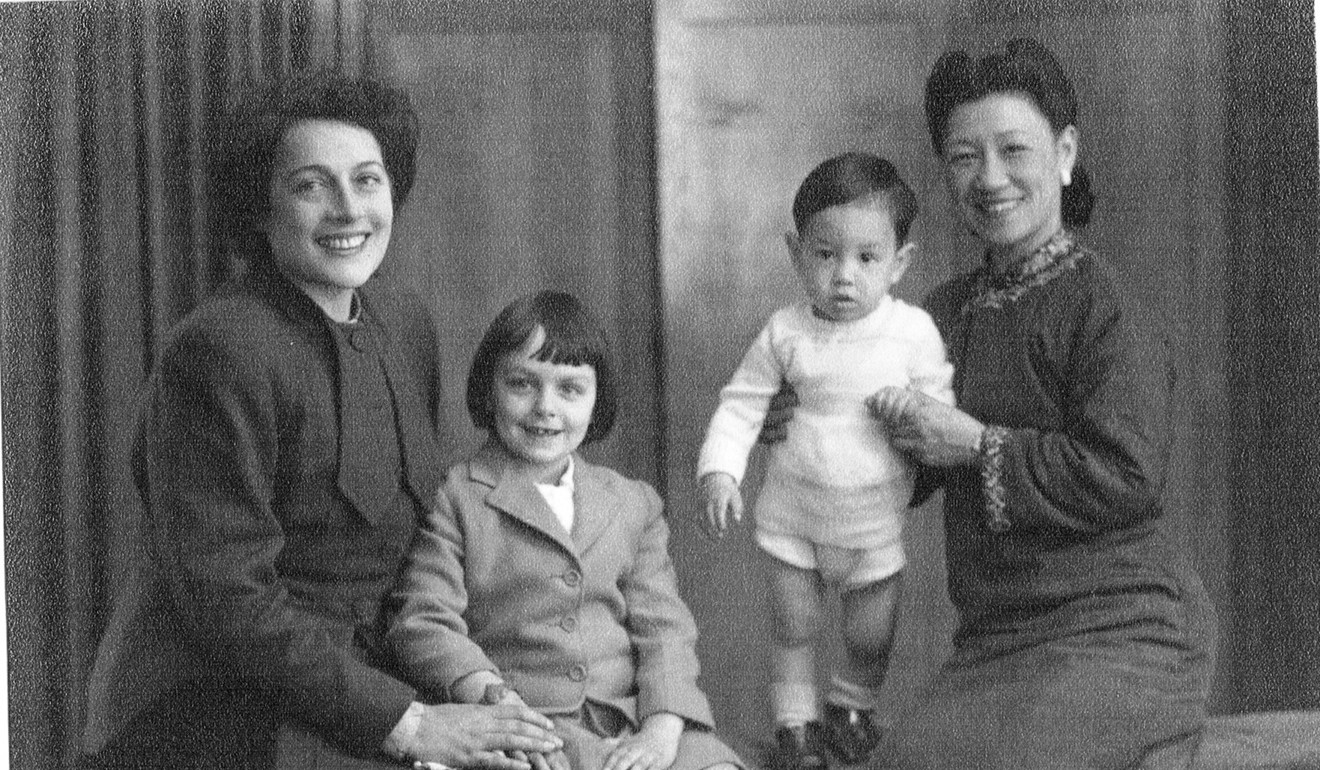

The writer who made the greatest impression on Newman, however, was Hahn, known to her friends as “Mickey”. With fashionably curled brown hair and a fox stole around her neck, the American looked like a model.

Despite a 10-year age gap, the two women hit it off. Hahn, who wrote for The New Yorker magazine, was curious about everyone and everything, and was drawn to the bright-eyed, energetic young woman who was a mine of information, including where to go for a permanent wave.

In turn, Newman was captivated by warm and worldly Hahn, a truly emancipated woman in a man’s world who did what she pleased and shrugged off disapproval.

“Mickey was unlike anyone I had ever met and she taught me more than anyone,” my mother told me. Hahn was an excellent listener and Newman could confide in her and count on sensible, if often unorthodox, advice. When Hahn realised Newman was supporting her mother on her small salary, she gave her work to type up and paid generously.

Hahn immersed herself in Shanghai society, becoming Shao’s lover and learning about China through his many family members. Her articles in The New Yorker about a fictitious Mr Pan, who was based on Shao, helped to fan intense American interest in China.

The inaugural issue of T’ien Hsia, published in August 1935, offered a mix of learned articles and book reviews that would earn respect from an international audience. Modern readers might find its style pedantic but Hahn, who became a regular contributor, said this reflected the Chinese love of scholarship.

In an editorial, Sun Fo lamented that improved communications had not produced greater international amity, and said that could be achieved only by concentrating on the good points countries shared rather than harping on their differences. T’ien Hsia, he affirmed, was born of a conviction that the key to this was cultural understanding.

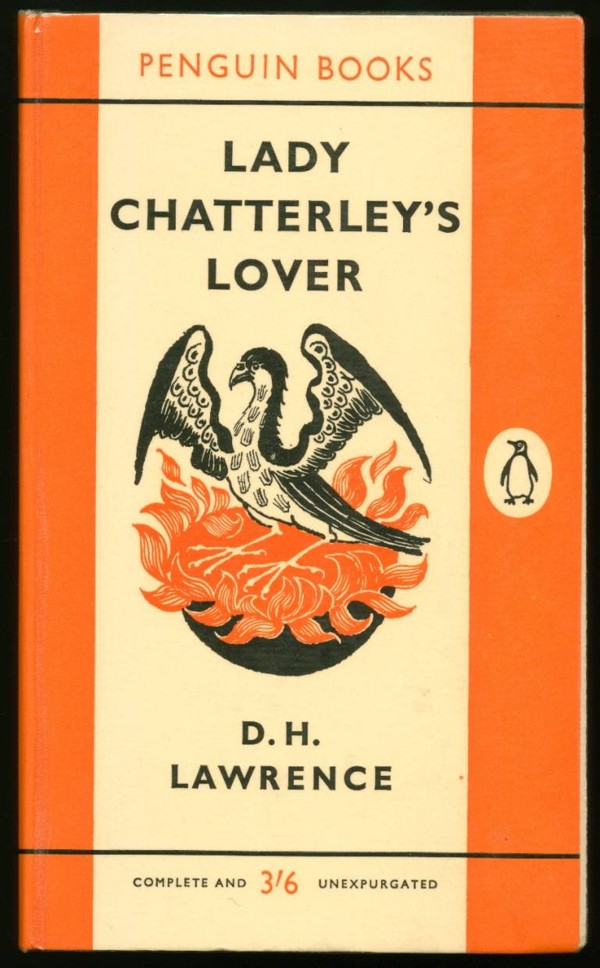

With this goal in mind, Wu wrote an essay titled “The Real Confucius”, Wen penned “Racial Traits in Chinese Painting”, and American scholar Owen Lattimore contributed an essay on “The Wickedness of Being Nomads”. But the highlight of the opening issue was a literary scoop.

Newman, meanwhile, had blushed at Lawrence’s graphic depictions of sex and this was one experience she did not relate to her mother.

Although T’ien Hsia promoted peace, its fate would be shaped by war. In July 1937, the Marco Polo Bridge incident, outside Beijing, led to fighting between Chinese and Japanese soldiers that sparked the “unofficial” Sino-Japanese war. By August, Japanese forces had reached Shanghai.

On August 14, Newman boarded a bus near the junction of Nanking and Tibet roads and, minutes later, heard a massive blast. A bomb had fallen near the spot where she had been standing and killed hundreds of civilians. It was the start of the battle of Shanghai, which would last for months.

The world’s media descended upon Shanghai and the mayor, Yu Hung-chun, asked Wen if he knew anyone with English and secretarial skills to help him out. Wen recommended Newman. Her first task was to take verbatim notes of the mayor’s press conferences, which had to be typed up and a copy sent to Chiang Kai-shek.

Newman became acquainted with the correspondents over dim sum and drinks before press conferences and the occasional dinner afterwards. One she got to know well was Pembroke Stephens, The Daily Telegraph journalist who was killed in the fighting in 1937.

After one press briefing, the mayor turned to Newman and said their radio broadcaster had been taken ill and he wanted her to replace him. Newman could not believe what she was hearing. He said she needed a pseudonym to protect her identity from the Japanese. He quickly came up with the name Billie Lee, after American film actress Billie Dove, who was popular in Shanghai.

Bemused, Newman was driven in a black, bulletproof limousine to the radio station. She was so nervous she had only a hazy recollection of her first news broadcast but the mayor called her afterwards to congratulate her and tell her that the job was hers.

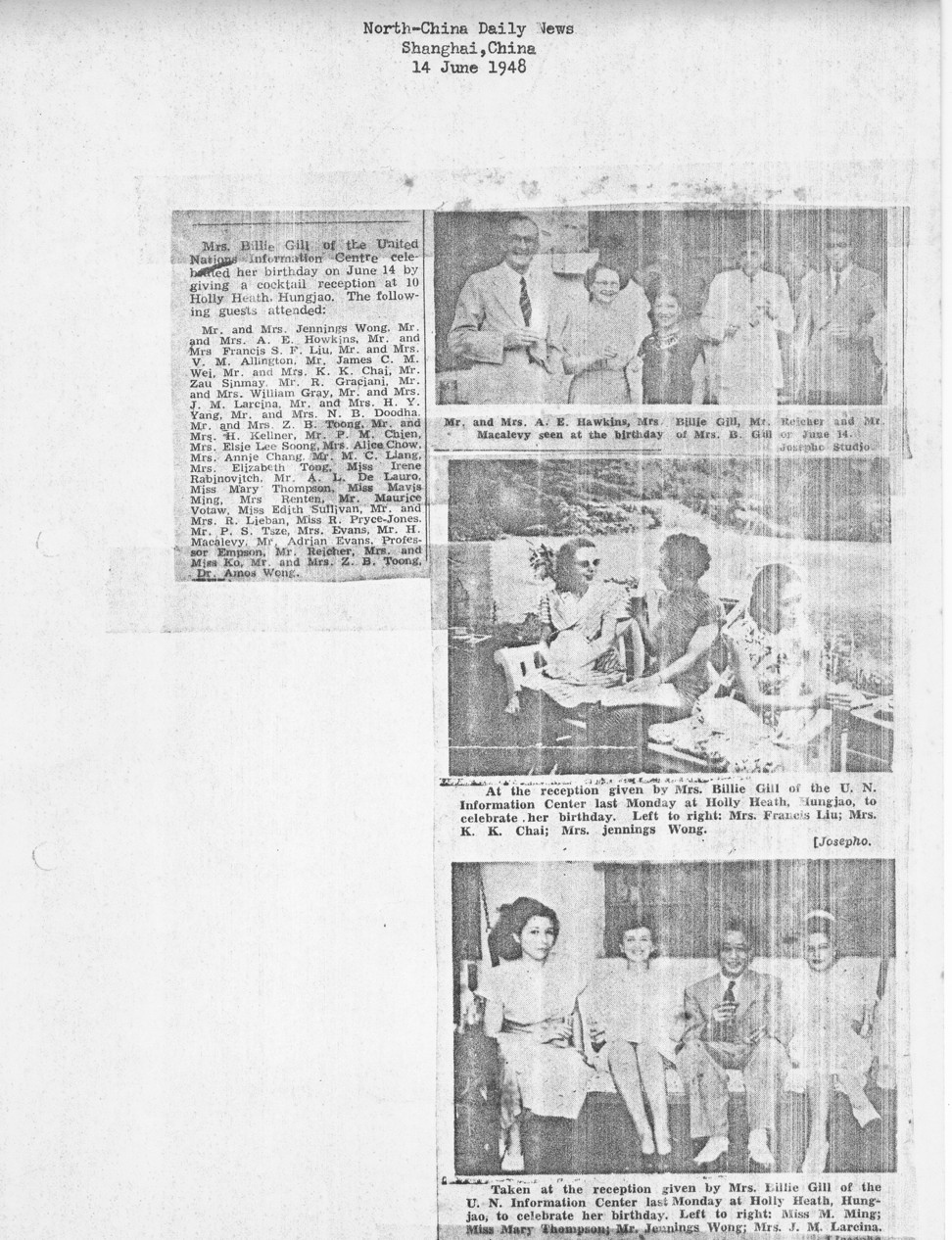

Radio was a popular medium and, over the next several weeks, the female broadcaster with a Chinese name and English accent became well known, even attracting letters with romantic intent. “Billie” became her lifelong nickname.

It was only a matter of time before Shanghai fell and Wen was concerned that T’ien Hsia staffers might be on a Japanese blacklist. In mid-November, Newman, carrying a ticket under the name Miss Feng, joined other staff on the vessel MS Aramis, bound for Hong Kong.

With the Chinese government based in Chungking (modern-day Chongqing), Hollington Tong, Chiang’s head of information, wanted to establish a presence in Hong Kong, with its links to the outside world. Tong asked Wen and his colleagues to set up the Chinese Government Information Office and to continue to publish T’ien Hsia. They took offices in the prestigious Hongkong and Shanghai Bank building in Central and Newman’s expanded duties included assisting correspondents such as Edgar Snow, Ernest Hemingway and H.J. Timperley on their way to China to cover the war.

She became close to the brilliant New Zealand writer Robin Hyde, who fell ill after she was stripped and beaten up by Japanese soldiers in China.

One of Newman’s most interesting extra assignments was to work for W.H. Donald, the long-time Australian adviser to the Chiangs, whenever he was in Hong Kong. To escape demands on his time, especially by local media, Donald would take Newman out on his yacht, the Mei Hwa, a gift from Madame Chiang, which had a small office with a teak desk.

In between taking down Donald’s memos on matters of state, Newman would take dips in the sea and snack on honeydew melons, a favourite of Donald’s.

T’ien Hsia added staff in Hong Kong, including Alice Chow, to organise stenographical services but, as Hahn wrote in her 1944 book, China to Me: a Partial Autobiography, “Billie did practically all of the real work that was done at T’ien Hsia”.

Hahn, who moved to Hong Kong in 1939, and Newman remained close. When Hahn, who had been introduced to opium through Shao, needed a “fix”, she would ask Newman to accompany her to an opium den and see her safely home.

Newman was courted by Gill, an Irish warrant officer in the British army, and they had a civil wedding on January 31, 1940, with T’ien Hsia colleagues Lesley Chan and his wife, Mildred, as witnesses. Billie Gill gave birth to her first son and lent moral support to Hahn, who once again became the subject of scandal after getting pregnant by Boxer, who was married.

On the morning of December 8, 1941, Billie was going to work on the tram from Happy Valley when she heard distant thudding noises. It was the dropping of Japanese bombs on Kai Tak Airport, signalling the war’s arrival in Hong Kong. From the office, she called her colleagues, who lived on Kowloon side, but she would not see them again for many years.

Ultimately, T’ien Hsia was a casualty of war, and was never resuscitated.

In 1946, my mother and I spent several months with the now-married Hahn and Boxer at their home in the British county of Dorset. After Billie contacted her T’ien Hsia colleagues, Tong offered her “an important position in China”.

She found later that she had, in fact, been earmarked as personal assistant to Madame Chiang, but there was a change of mind when it was realised she was still close to Hahn, who, as a writer, was hardly the soul of discretion.

Billie began work as a feature writer for the government’s information office in Nanking, but China was going through hyperinflation and her monthly salary, which had sounded impressive in Tong’s job offer, proved almost worthless. Tong helped her get a job with the United Nations in Shanghai.

Billie felt awful at abandoning her colleagues but kept in touch, and T’ien Hsia writers Shao and Empson came to her 32nd birthday party in Shanghai in 1948. By then, Wen was an ambassador in Greece; and Wu, whom Billie had asked to be my godfather, was ambassador to the Vatican.

T’ien Hsia, a cultural icon of its time, became a neglected part of history, but the bonds it had forged lived on. In 1975, my mum took me to Taipei to meet Wen and Wu. Though largely immobilised by a stroke, Wen was dressed in a three-piece suit to meet us.

Wu, who was in good health, gave me a crystal rosary as his godson. In Hong Kong, Billie called Lin but he was unwell, broken by the suicide of his eldest daughter. Shao had been arrested for spying in 1958 and died during the Cultural Revolution.

T’ien Hsia had been the making of Billie and she would maintain her friendships. From Geneva, Switzerland, where she retired after a long career with the UN, Billie visited Hahn and Boxer periodically, until the American writer died in 1997, and her husband passed away in 2000.