Now China refuses to be dumping ground for the world’s waste, where on Earth will it all go?

Plastic, paper, metal – with other countries unable to handle the sheer volume of recycling needed, the planet’s trash is piling up

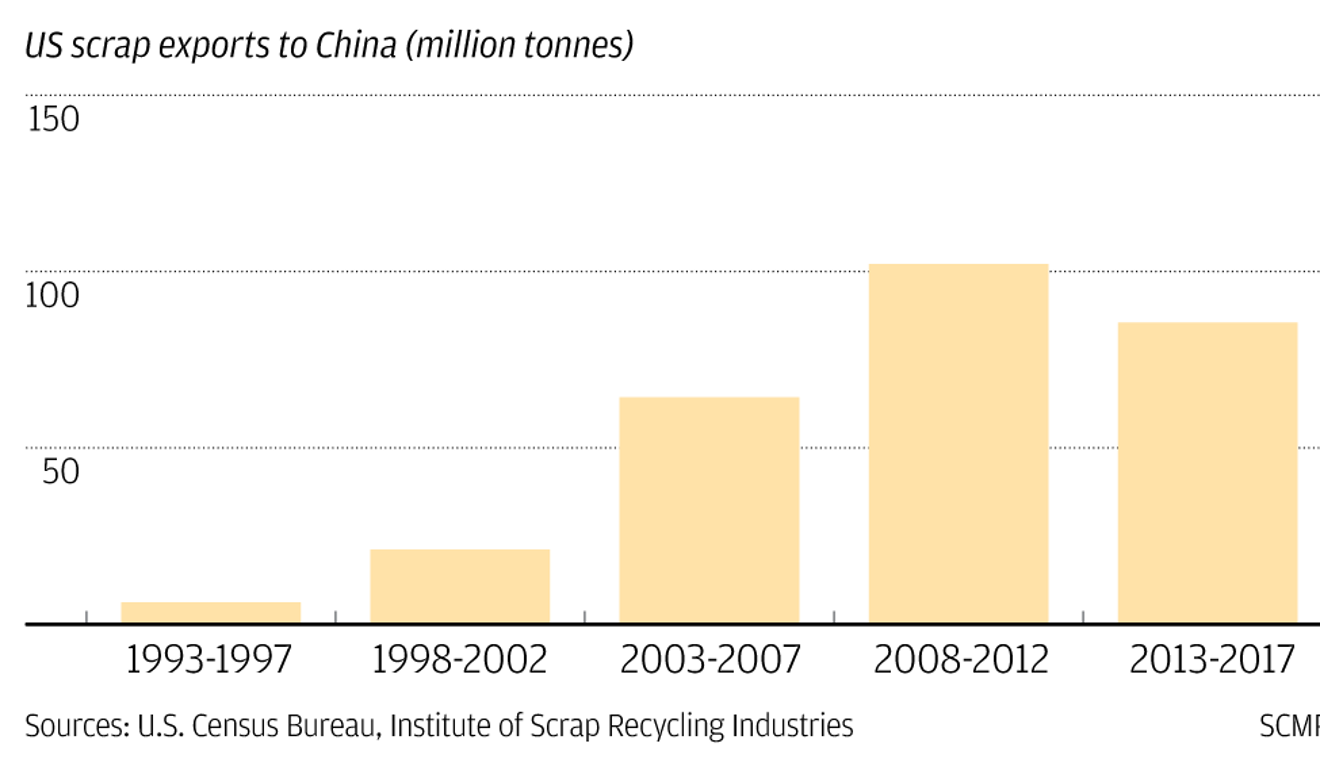

In recent decades, China has been the world’s largest importer of waste, accepting some 279 million metric tonnes of America’s scrap alone over a quarter of a century, including paper and plastic for recycling, as well as mountains from Japan, countries in the European Union and from the developing world.

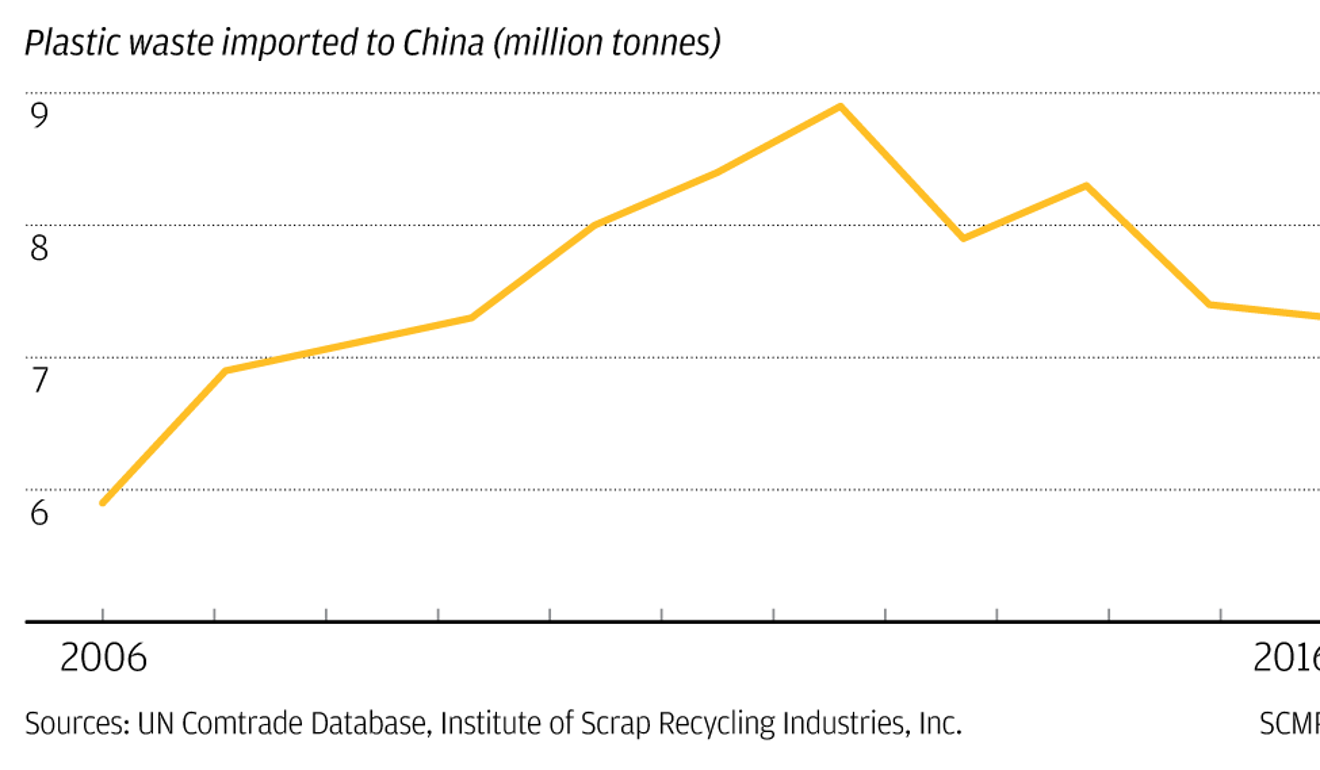

According to Greenpeace, China had become the dumping ground for more than half of the planet’s scrap, at its peak importing almost 9 million tonnes of plastic trash annually. A paper, published last month in the journal Science Advances, says that China imported 106 million tonnes of plastic waste for recycling since 1992.

China’s waste ban is a wake-up call for the world

This year, however, China said, “No more!” So where should or could the planet’s recyclable junk now go? Britain has looked to Southeast Asian nations, offloading more waste on Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam in the first half of 2018 – but such countries have nowhere near the capacity for scrap as China.

Bloomberg Opinion columnists Faye Flam and Adam Minter met online recently to discuss the global recycling crisis – and to ask what, if anything, we can do about it.

Minter, an American, has covered the global recycling industry for more than a decade. As well as having produced a series of groundbreaking investigative pieces on China’s recycling industries, he is author of the book Junkyard Planet: Travels in the Billion-Dollar Trash Trade (2013).

Also from the US, science journalist Flam has written for The Economist, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Psychology Today, Science and other publications. She has a degree in geophysics from the California Institute of Technology.

Is there much that any single member of the bottle-rinsing public can do to resolve this recycling crisis?

Adam Minter: I think there are two misconceptions surrounding responsibility for the plastics and recycling crisis. The first is that it originates out of individual actions. In fact, less than 10 per cent of the waste generated in the US, Canada and the EU comes from households. Instead, it’s further up the production chain – farms, factories, distribution points, retailers. So that means addressing the problem more systematically.

The second misconception is that developed countries are the source of the problem. A 2015 study points out that the vast majority of ocean plastics actually originate in developing countries without good waste-management systems, no trash pickups, informal landfills.

Faye Flam: I once interviewed a biologist who decided to start living plastic-free after studying birds on an island in the Pacific. She was cutting open these dead birds and finding hundreds of pieces of plastic. For some reason we seem to be very bad at disposing of our plastic trash properly. It should go in landfills if it’s not recycled, but millions of tonnes end up in the ocean.

So people can drink from plastic soda bottles guilt-free?

Flam: It’s good to know that industrial plastics contribute more to the whole, but we consumers still throw away a lot of plastic and many of us would like to do it in the least harmful possible way. There’s a desire to help.

Minter: Faye makes a good point. Of the three Rs – reduce, reuse, recycle – I’d argue that the last one gets too much attention, and the first not enough. I think it’s important to be realistic about the limits of recycling.

Can technology help solve this problem?

Minter: There’s no question that technology has always played a role in recycling. It goes back to the first time somebody held a sword over a fire and turned it into a ploughshare. But technology has never driven recycling. Instead, it’s the demand for raw materials – cheap raw materials – to make new stuff.

When China started importing foreign recyclables in the mid-1980s, it wasn’t because they had any great new insight into how to process paper, metal or plastics. Rather, they were undergoing a manufacturing boom, and they needed cheap and easy-to-access raw materials to make it go. Recyclable metal is cheaper than virgin metal, and that’s what they imported.

Let’s have a hi-tech solution to recycling

Then, rather than throwing new technology at the problem, they threw millions of labourers at it. As a result, recycling rates around the developed world skyrocketed as the price of recyclables rose. So the challenge now is creating new markets to replace the ones that are fading away.

Technology might help that cause. But simply relocating or expanding older technologies in places where recycling is generated, like the US, is something that can happen now – assuming somebody sees the financial incentive to do it.

Flam: That is interesting, but as the cost of labour goes up in China, who will take up the slack and sort through our mountains of plastic trash? Are there other countries who will be able to profit from recycling it?

Minter: There’s no single country that can replace China’s recycling capacity. But over the last six years, we’ve seen material relocating to Southeast Asia. Manufacturers have followed. Long-term, India’s manufacturing industries will also become major importers.

One additional point on this: a recent study says 111 million metric tonnes of plastic recyclables will be discarded [globally] over the next decade. The number could be even higher. But it’s not as if that material will be openly dumped. There’s more than adequate landfill and incinerator capacity in the US to ensure it doesn’t end up in the oceans. The calculus now must be: does it make more sense, environmentally and financially, to build up recycling capacity in the US? And I think that’s where technology might provide some answers. But first, we’ll want to see the demand for those goods.

Flam: One of the challenges the chemists tell me we face is the great variety of plastics. They can’t be recycled together, but there are chemical tricks that could make them compatible so that recyclers of the future could skip all that sorting that now requires human labour.

Minter: Do you have any sense about the quality of the plastics that would come out of those processes? Would they be as good as virgin plastics?

Flam: It would likely be about the same as recycled plastic now. It’s not good enough to make into new bottles or containers. That’s where other chemists and chemical engineers are making progress. Current recycled plastic is really “down-cycled” into lawn chairs and the like, but people have invented plastics that could be made into the same bottles or containers hundreds of times.

How Hong Kong can recycle more, and the red tape holding it back

Minter: That would be a game-changer. Do we have any sense of what kind of environmental impact those chemical processes would have? One problem regulators are facing is that some recycling is more environmentally harmful than the process of manufacturing new. I wonder if this solves that.

Flam: It depends on people’s priorities and perhaps on changes in regulation. Back in the 1980s, scientists had realised that a very important class of chemicals was destroying the ozone layer. Finding substitutes looked hard, but it happened once there was an international treaty.

Speaking of which – is there an analogy here with climate change? In that case people who cared about it pressured public officials to take action, such as joining international agreements. What is the equivalent for people who care about recycling?

Minter: Multiple studies show that improving waste collections in developing countries are the best way to reduce ocean plastics. There’s a small but growing movement, started by a group called WasteAid UK, to push international aid agencies to devote three per cent of their budgets to waste management (currently, they devote about 0.3 per cent). I think that’s worth lobbying for.

Flam: Scientists tell me they need public support to do the research necessary to improve energy efficiency, develop alternatives, capture carbon from the atmosphere and ultimately develop plastic that can either be recycled indefinitely or will safely degrade.

I was in Haiti a year or so after the earthquake, and was struck by the mountains of plastic trash. But a big portion of it consisted of water bottles, which were important for getting clean drinking water to people, and probably for saving a lot of lives. The key was finding a way to motivate people to collect the waste, so it could be profitably recycled or safely disposed of. So they started a programme to pay the local residents to collect plastic for recycling.

You both seem to be giving the developed world a pass here.

Minter: Not at all! But if we’re going to focus on where the ocean plastics problem can be addressed most effectively and efficiently, it has to start in the developing world.

How China is giving a recycling lesson to Hong Kong and others

Flam: I think supporting research is good. Supporting better disposal infrastructure in places like Haiti also makes a difference. There are probably ways to better organise things in places where plastics are going into the oceans. And it can’t hurt for people to take the extra step of checking the Web to see what your local communities accept. As Adam mentioned, there are projections that the world will throw away as much plastic in the next 11 years as we’ve discarded since 1950. So if we think we have a problem now, it’s only going to get worse.

Bloomberg