Chinese Labour Corps: the first world war’s forgotten army, all but airbrushed out of history

- Overlooked for almost a century, China’s human contribution to the Great War is finally getting the recognition it deserves

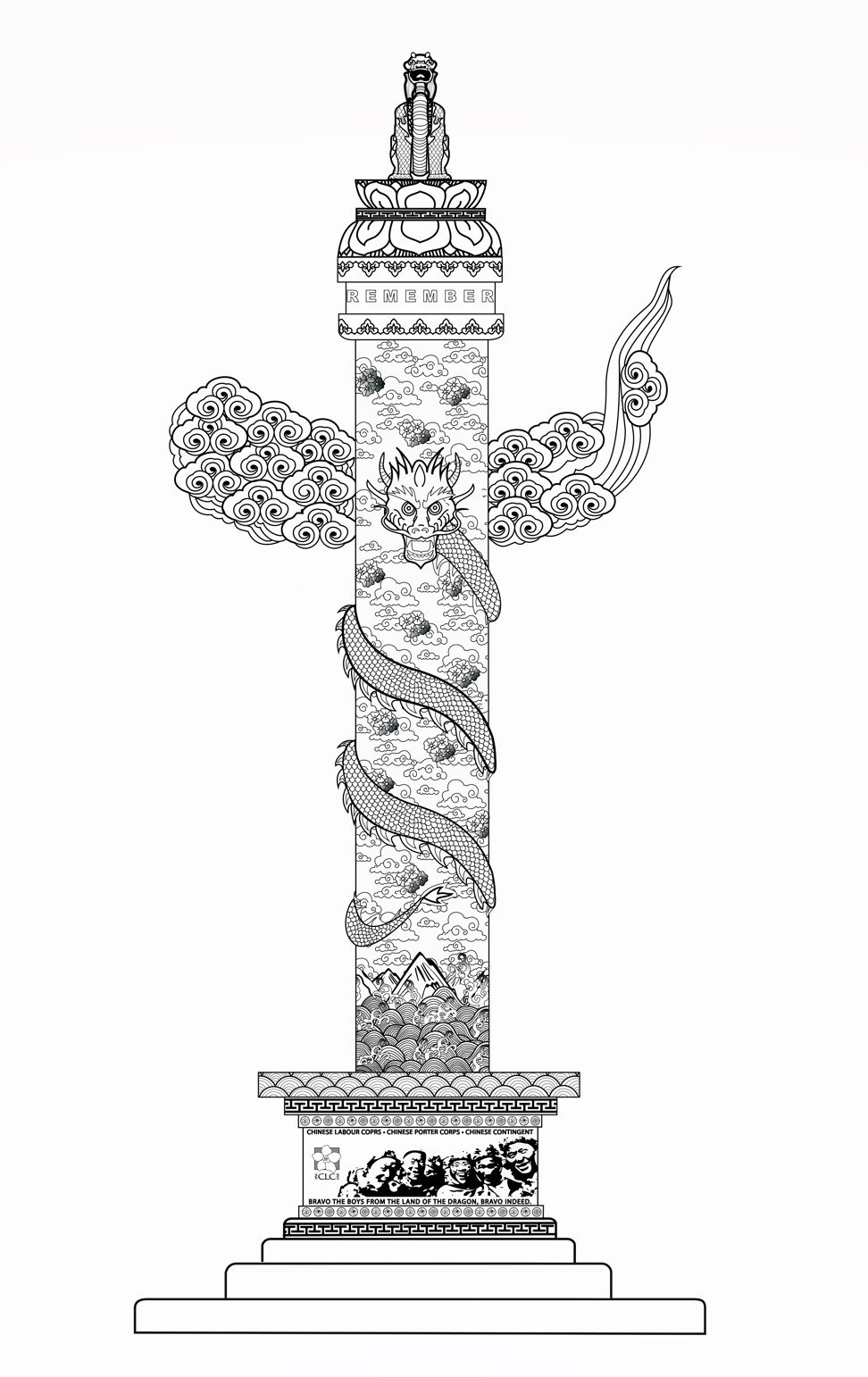

An imposing memorial, carved from white Hunan marble, is poised to make the same long journey to Europe as the men that it commemorates. The monument, a 9.6-metre-high huabiao – a traditional ceremonial column – is in the final stage of production at a stonemasons in Shijiazhuang, Hebei province. When finished, it will honour the tens of thousands of Chinese who, a century ago, served on the first world war’s Western Front.

Once erected in London, the huabiao will serve as a permanent reminder of the men sent to save the overstretched Allies. Their deployment was a tactical move by China’s fledgling Republican government, which was seeking respect and a place at the top table of world affairs. It was a policy gamble that ultimately failed, and one that resonates powerfully in China to this day.

How Chinese labourers helped shape Europe

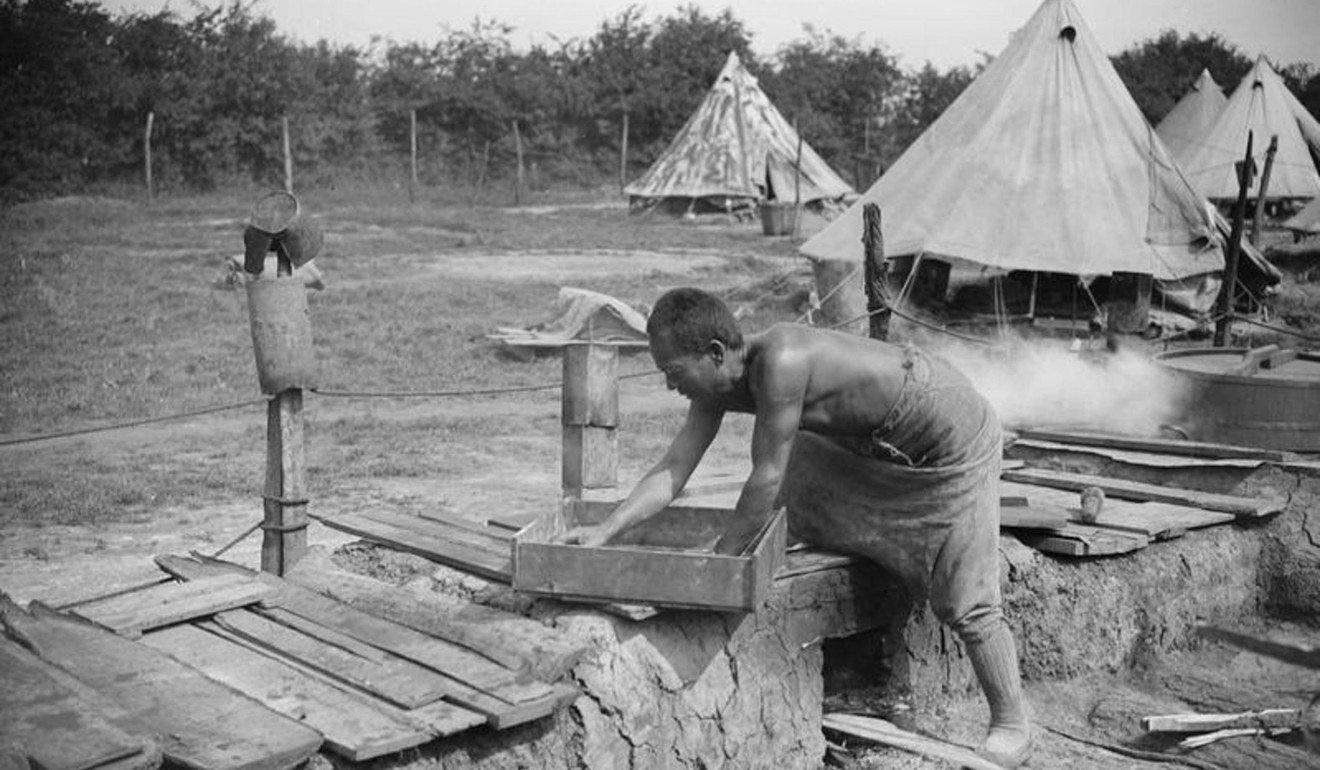

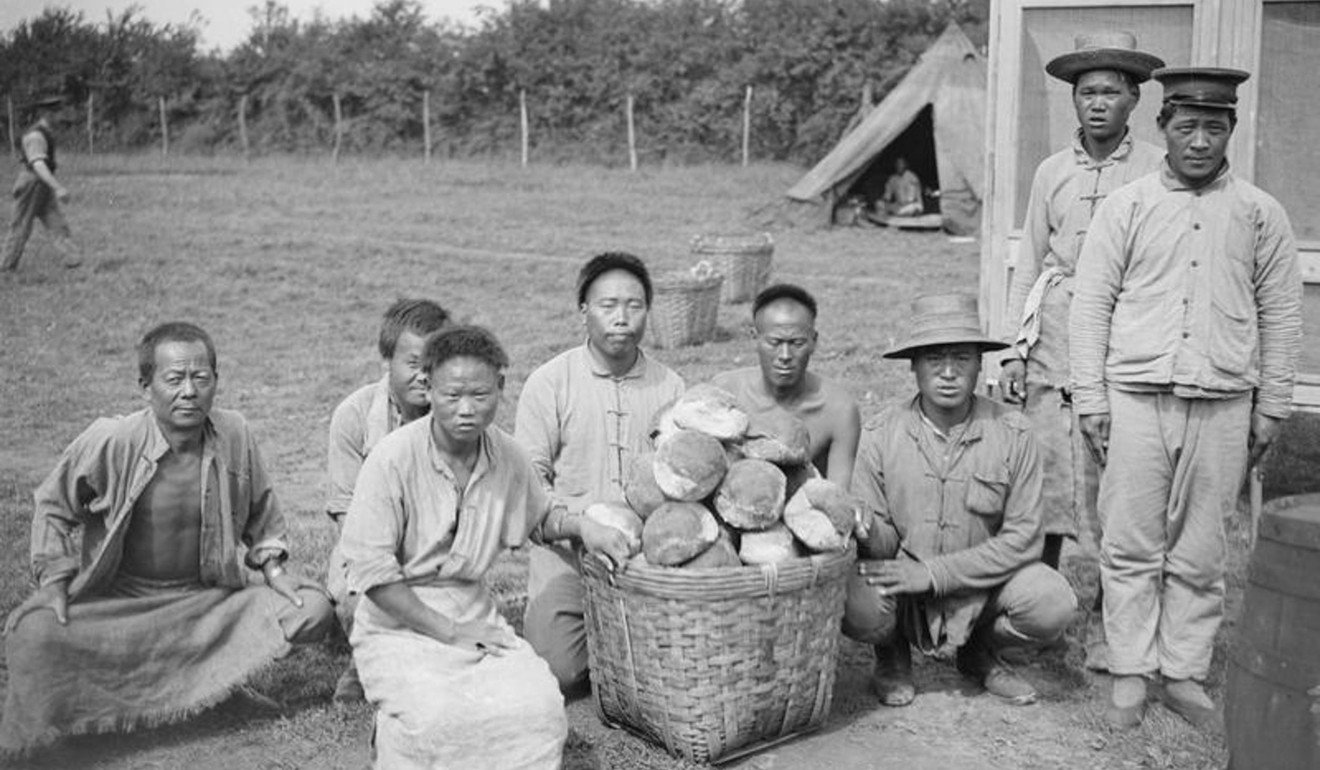

Over the past decade, the story of China’s human contribution to the Great War has received some of the attention it has long been denied. Some 140,000 mostly peasant farm workers, joined the British and French, and another 200,000 enlisted with the Russians. All were sent as non-combatants, and they would dig trenches, bury the dead, carry the wounded, make and transport munitions, and fix tanks, aircraft and bombed airfields – the jobs that would release European manpower to fight against the German-led aggressors.

After the war, the Chinese cleaned up battlefields and buried more of the dead, including members of their own ranks.

Most of the men were recruited in northern China, and the first group arrived in France in April 1917. By the time the armistice to end the war was signed, 18 months later, 96,000 Chinese were working under British command and 40,000 under French. Those who went to Russia had been contracted by Chinese companies.

Awareness of the ragtag army of mercenary grafters has risen exponentially year on year: several books have been published on the subject, documentaries made and museum installations showcased; there have been seminars and talks, and most recently a stage play in Britain.

A poppy wreath is now laid alongside the hundreds of other tributes at the Cenotaph in London on Remembrance Sunday. In August, at a gathering held at a cemetery in Liverpool where five members of the CLC are buried, an official representative of Britain’s Queen Elizabeth recognised the men for their commitment to the cause of freedom while placing themselves in danger.

It amazes me how few people know about the contribution made by the Chinese in helping Britain and its allies win the Great War, and I think if they knew how crucial they were in that victory, then some of the stereotyping of the Chinese in Britain would cease

About 2,000 such men lost their lives in Europe and an unknown number perished on the Eastern Front, in Russia; to borrow from the poem The Soldier, by first-world-war poet Rupert Brooke, there are many corners of foreign fields that are for ever China.

That Chinese wartime labourers are now being placed at the forefront of remembrance alongside their Western brethren in Europe corrects a historical oversight in the geopolitical narrative of the past 100 years. And, the small band of campaigners and donors believe, a permanent memorial in London will help battle long-held prejudices.

“It amazes me how few people know about the contribution made by the Chinese in helping Britain and its allies win the Great War, and I think if they knew how crucial they were in that victory, then some of the stereotyping of the Chinese in Britain would cease,” says Steven Lau, chairman of the Ensuring We Remember campaign, which brings together community groups, trade bodies and private donors in the cause of remembering the CLC.

Supply lines are the lifeblood of armies and decide the outcome of wars. Having lost some 2 million men by 1916, the British and French, after resisting initial offers from Beijing of combat troops, ordered Chinese non-combatant labourers to Europe. Without them, the war might have raged on for longer than it did, and perhaps the Allies would have lost.

“The memorial huabiao will be an impressive, permanent installation that will help tell an important part of history,” adds Lau.

Few nations avoided being sucked into the slaughter of the Great War, and anniversary ceremonies to mark the centenary of the armistice are taking place around the world on November 11. There was, of course, a global celebration a century ago, when the Germans signed – on that day in 1918 – an acceptance of defeat aboard a train halted in the Forest of Compiègne, in France, and which came into force at 11am, Paris time (“the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month”).

From London to Peking, crowds took to the streets to celebrate the end of four long years of bloodshed, and China had much to cheer about. Not only had it sent men, it had taken a risk and sided early on with the Allies, eventually declaring war on Germany, which held concessions in Shandong province, including Qingdao and Yantai, in 1917.

Ending up on the war’s winning side was a watershed moment for the young Republican government. Barely seven chaotic years into its quest for democracy and modernisation, it believed it had come of age. President Xu Shichang had been in power for only a month or so, and with his administration weak and divided, he sought to capitalise on the feel-good factor. He ordered a three-day national holiday and a victory parade.

Citizens spilled onto Peking’s streets, some attacking German banks. Students paraded with British Union and French Tricolour flags, while the American Legation band played the national anthems of all the Allies, including that of Imperial Russia.

But within months, jubilation had turned to humiliation and revolt. The Republican administration, egged on by Washington, had joined the war believing that after victory, the German concession ports would be handed back and the new Republic would be counted as a loyal partner worthy of respect and consultation in the post-war world.

But the Chinese delegation sent in January 1919 to the Paris Peace Conference was unaware that a secret deal had been made between others in the fractious Peking administration and the Allied powers. During the international gathering, chaired by United States president Woodrow Wilson, the Western alliance believed Japan would be more likely to join the League of Nations if allowed to take permanent control of Germany’s former China concessions; Tokyo had grabbed the ports after the outbreak of war in 1914.

The decision in Paris was a pivotal moment in modern Chinese history. The collapse of the first Chinese republic, widespread warlordism, Japanese annexation, civil war, the 1949 revolution and 70 years of unchallenged Communist Party rule, which has steered China – albeit painfully – from “sick man of Asia” to global superpower … all can be traced back to the 1919 Treaty of Versailles.

Chinese Labour Corps’ service in first world war has not been forgotten

With news of the agreement with Japan having reached China, 3,000 students and members of the middle-class intelligentsia demonstrated in the streets of Peking on May 4, 1919, decrying the internal and external treachery. The students burned the house of the minister of communications and assaulted China’s minister to Japan – both of whom were pro-Japanese officials.

Over the following weeks, demonstrations occurred throughout China; several students died or were wounded and more than 1,000 were arrested. Strikes and boycotts of Japanese goods took place in large cities, with merchants and workers coming out in support of the students.

The unstable government, still trying to find its feet since declaring China a republic in 1911, caved in to the public’s demands; three pro-Japanese officials were dismissed, the cabinet resigned and the Chinese delegates refused to sign the treaty.

But the genie was out the bottle and the May Fourth Movement, as it became known, continued to push for change. A campaign rolled out across the provinces to reach the peasantry: mass meetings were held and more than 400 new publications appeared to spread the message and demands for a new culture of modernity and strength, and for an end to foreign occupation.

The movement was the well from which sprang a resurgent, revamped Nationalist Party, also known as Kuomintang, led by Chiang Kai-shek, and it forged the Chinese Communist Party. For those who know their Chinese history – and for those who want to know how China arrived where it is today – dates do not come more significant than May 4, 1919.

The huabiao heading for London is, after a series of setbacks and delays, now scheduled to be unveiled on May 4, 2019 – the 100th anniversary of the day China began its painful journey towards becoming a 21st-century global superpower.

Britain commemorates China’s forgotten war dead

The huabiao’s unveiling was originally scheduled for November 11, to chime in with worldwide events marking the anniversary of the 1918 armistice. And it was to stand in a new development – being built by Chinese-owned international development company ABP – at London’s Royal Albert Docks, where many of the labourers disembarked after their long sea and land journey from China.

ABP, however, has since scrapped that plan due to a hold-up at the stonemasons in Hebei. To cut down on pollution, the Shijiazhuang government recently slapped a ban on stone-carving businesses, which have been blamed for causing excessive dust in the city. That, at least, was the reason given to Lau.

“We have parted company with ABP on amicable terms,” he says. “For reasons which are entirely understandable, they required us to be able to deliver what was required by them within the overall framework of their own £1.8 billion [US$2.4 billion] development.”

Eyebrows were raised over the anti-pollution story, with some wondering if China’s nuanced politics had come into play. To shut down a whole industry would surely spark wide protests over lost revenue and jobs: could it be that officials have deemed the monument something President Xi Jinping would not approve of?

The involvement of Chinese labourers in the first world war and the subsequent anti-government protests are facts the Communist Party might prefer remain forgotten.

Lau dismisses the idea of a conspiracy, saying he is not aware of any high-level interference, and Post Magazine understands that Beijing donated, via the Chinese embassy in London, £50,000 to the memorial campaign, which has raised £250,000 in total from public and private donations.

In pictures: the Chinese Labour Corps in the first world war

“It may seem the Chinese government is using very blunt instruments to address the pollution issue. I can only say it is beyond my competence to comment, let alone suggest better ways of addressing the issue,” says Lau, who flew to China last month to check on the huabiao’s progress, and to attend a conference on first-world-war labourers in Shandong, from where many were recruited. “We’re working with the situation that presents itself, and accept production has taken longer than we expected.”

The impasse is an anticlimax to a dogged campaign. “Some of the donors are getting nervous. A lot of money has been given to fund this,” a member of the British-Chinese community, involved in commemorating the CLC, says. But Lau remains adamant: the huabiao will make the journey from China, he insists, and it will be erected somewhere in London on May 4 next year.

A planning application was lodged earlier this year to erect the monument in Newport Place, a newly pedestrianised area at the east end of Gerrard Street, the main thoroughfare of London’s Chinatown.

“There is a lot of support for Chinatown, but ultimately it’s the support of the planners that is important, though we could appeal to the London mayor, Sadiq Khan, who has publicly committed to supporting the campaign,” says Lau. “Could we do this, if we needed to, and be ready for May? I think so.”

Other sites have been proposed, but “Chinatown is the ideal, and obvious, place, and we are actively supporting the huabiao’s presence here,” says Edmond Yeo, chairman of Britain’s Chinese Information and Advice Centre.

Once erected, the memorial will honour men such as Soo Yuen Yi, who, aged 19, in 1916, overheard men passing through his small village in Taishan county, Guangdong province, talking about well-paid work for foreigners in Europe. He joined them, walking to the recruitment office in Hong Kong.

After a medical, signing with his thumbprint a contract to work 10 hours a day, seven days a week with time off for Chinese holidays, and being given two sets of clothes and a bedroll, he boarded a ship for Canada, where he and thousands of his peers were put on trains for the Atlantic coast. There, they boarded another ship, bound for Europe. The route took three months to complete and began being used after a German U-boat had holed a transport ship sailing the shorter journey through the Suez Canal and into the Mediterranean.

Soo’s relief at reaching his destination was short-lived. Despite the contract stipulating the Chinese would work on farms or in factories, and would not be involved in military operations, Soo was sent close to the front line, in France.

He was promoted to foreman joiner for the Fleet Air Arm, forerunner of the Royal Air Force, at its French headquarters, in Saint-Omer, in the Somme region.

“I knew him as ‘Grampy’,” says Soo’s granddaughter, Karen Soo, who was born and raised in Britain, and promotes CLC commemoration events. “He left his tiny home village after hearing of an opportunity of work to provide for his parents. Our grandfather was young, fearless, hard-working and optimistic, driven by a strong sense of family duty and responsibility.

“He travelled to Hong Kong, busking with his bamboo flute. Like most of the men who signed up, the other side of the world was a mystery, as alien as the moon.

France honours ‘forgotten’ Chinese labourers who helped war effort a century ago

“Grampy learned some French and became friendly with his Western officers. He was put in charge of a squad tasked with keeping the airfield operational, filling in bomb craters and repairing runways for the Allied planes to land and take off, sometimes when bombs were still being dropped around them.”

Using his carpentry skills, Soo also helped maintain aircraft, and after the armistice, like thousands of his compatriots, he stayed on to clear tonnes of munitions and make the land safe. It was hard, dangerous work at a time when a deadly influenza epidemic was sweeping across Europe, and the men also faced hostility, racial abuse and prejudice from returning locals.

Late in 1919, Soo found passage on a ship bound for the US. Family lore has it that he disembarked in Liverpool, England, by mistake, believing he was on the eastern seaboard of the US.

“Whether true or false, our family’s fate was sealed,” says Karen. “He made his way and ran his own laundry business in Liverpool before moving to Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, and after overcoming much initial, often hostile, prejudice – his was the first Chinese family in the town – he became a popular and well-respected member of the community.”

Soo died in 1980, aged 83.

“Having survived the bombs, the bullets, the disease, the landmines and the influenza that swept through the camps after the war, as well as the mental challenges of being so far from home, he was a fiercely robust person in body and spirit, and he remains in my memory as a strong and kindly grandfather,” says Karen, who recently made a pilgrimage to the Somme.

I think it is very important to remember those 140,000 Chinese labourers and their contribution. As a British-born Chinese, I am proud of what men like my grandfather endured both during the war and after

“It was moving for me to step on the very ground that he walked on 100 years ago, though in very different circumstances. I think it is very important to remember those 140,000 Chinese labourers and their contribution. As a British-born Chinese, I am proud of what men like my grandfather endured both during the war and after. We should all pay our respects and learn about their story. They were also heroes of the Great War and should be counted as such.”

An hour’s drive from the Saint-Omer airfield is Nolette Chinese Cemetery, at Noyelles-sur-Mer, where 841 of Soo’s fellow labourers lie. Located on the banks of the Somme river, just before it meets the English Channel, Noyelles-sur-Mer was the site of the base depot of the CLC in France, with its largest camp and a hospital.

I arrive late in the day from Dieppe’s ferry port, with the light fading. The cemetery is well signposted in French and English, and entered through a traditional paifang arch. The white gravestones face eastward, towards home, and the majority have only a serial number and a simple epitaph reading, “A noble duty bravely done”, or “Though dead he still liveth”, or “A good reputation lasts forever”.

I hurriedly look for and find two headstones: Labourer 106882, who died on November 11, 1918, and Labourer 109324, who was declared dead on May 4, 1919. The dates, of course, are filled with meaning.

The next day, I return to the cemetery and refer to its list of occupants. Labourer 106882 was Sung His P’eng and Labourer 109324 was Chao Huai Ch’ing. Where they were from, their ages and the circumstances of their deaths are not recorded.

Quiet contemplation of the loss of Chinese lives, to which the cemetery is testament, raises the question: why has it taken so long for their wartime contribution to be recognised? The answer: when the guns fell silent, most Chinese were repatriated and forgotten, their presence during the conflict – literally, in one notorious case – erased from history.

The insignificance of the Chinese in the eyes of the Allies can perhaps best be understood by considering what was once the world’s largest painting, Panthéon de la Guerre. The 123-metre-wide, 14-metre-tall panorama – a smaller version of which now hangs in the National World War I Museum and Memorial, in Kansas, in the US – was commissioned in 1914 and depicted France victorious, surrounded by all her Allies.

Then, with the painting all but complete and the canvas covered, the US entered the war. The artists were ordered to include the Americans, and members of the CLC were painted out to make way.

The amnesia of the countries the labourers served, and of the Chinese elites who recruited them, is explored in a new play, Forgotten, by British actor and playwright Daniel York Loh. Employing English verse and Chinese Opera, the story moves from the fields of China to the bloody Western Front, exploring the lives of a band of hapless farm workers who at home had doubled as a performing troupe. Their naivety is exploited soon after signing up, resulting in resentment and anger.

They say history is written by the victors. But the Chinese labourers were on the side of the victors and yet still managed to get airbrushed

York Loh’s ambitious production, which is playing at London’s Arcola Theatre, has received mixed reviews, its use of Confucian proverbs and Chinese idioms perhaps losing newcomers to the Chinese first-world-war story. Towards the climax, one character expresses dismay and hurt at the painting over of the Chinese in the Panthéon de la Guerre, and he flings paint at it, causing what York Loh describes in the play’s script as a “bloody red mess”.

“They say history is written by the victors. But the Chinese labourers were on the side of the victors and yet still managed to get airbrushed,” York Loh says, adding that plans are afoot to take the play to schools, colleges and community groups.

“I would love it if the script, which has been published, could be translated into Chinese and other languages, and performed in places like Hong Kong or on the mainland, and anywhere with a Chinese diaspora,” he says. “It’s a part of history few Chinese know about.”

Cheng Ling and Dong Meijing, from Shandong, know the story well. Both are descendants of CLC members and are in Britain to take part in ceremonies to mark the armistice.

Dong’s grandfather, Chun Lin Ma, survived the war and returned to his village of Weifang to become a teacher.

“He kept a diary and I and my family have learned all about his hard trip to Europe and his dangerous work out on the battlefields of France,” says Dong.

Earlier, Dong and Cheng travelled to Efford Cemetery, in the naval port of Plymouth, where eight CLC men are buried – they never made it to the front line because they died from “heart attacks, pneumonia and other fevers” en route, their bodies laid to rest when the transport ships docked at their first port of call after the Atlantic crossing.

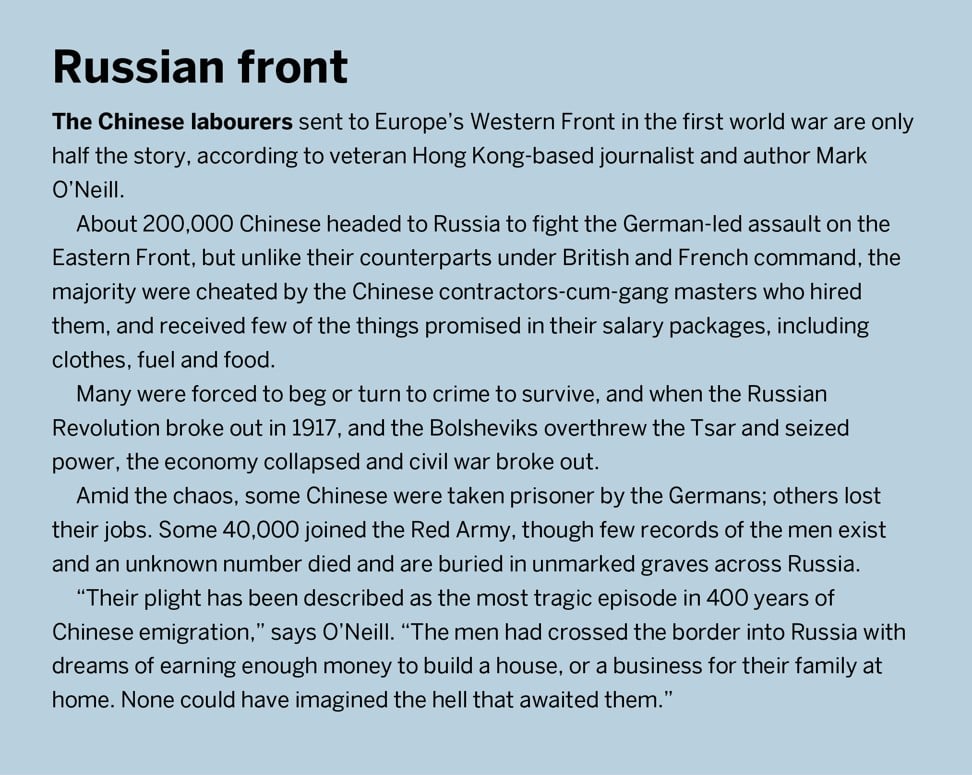

The fates of 200,000 Chinese workers in Russia during the first world war

Dong and Cheng laid poppy wreaths, white chrysanthemums and traditional offerings on the graves.

Flanked by standard bearers and a Royal Navy guard of honour, Cheng addressed dignitaries, including Counsellor Lu Haitian, from the Chinese embassy in London, and British Royal Navy Commander Jeremy Churcher, and retold how, after a long search, she had found her grandfather’s grave.

Bi Cuide left Shandong for war in 1917, and after landing in Britain, was transferred to France. He was clearing no man’s lands nearly a year after the armistice when a shell went off, killing him instantly. He is buried in the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) British Cemetery, at Beaulencourt, in France. As she spoke, Cheng grasped a red envelope in which she keeps her grandfather’s CLC medal.

“My grandmother was sent the medal with a short letter saying that her husband had died,” she tells Post Magazine. “Growing up, I remember her and my own father being very upset whenever grandfather was discussed.”

They had no idea how Bi died, or where he was buried or about his time in Europe – all they had was the ribbon with the engraved head of King George VI.

“When my father died, the only connection I had to the past was this medal. So I started researching my grandfather’s life. That was over 20 years ago, when there were no records in China and no one knew about the CLC and the war,” explains Cheng.

In 2001, her daughter travelled to Britain to study and took with her the details of the serial number printed on the medal.

Infographic: the shot heard around the world

“When there, she contacted the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, which checked their records, and said a CLC member with the same serial number was buried in France.”

Cheng has visited her grandfather’s grave three times since.

“On my first visit, there was just his serial number and date of death, 27.9.1919. On the second trip, the CWGC had added his name in Pinyin. And when I visited last time, they had engraved his name in Chinese, too,” she says. “I now feel that his life and bravery have finally been told, and that there is proof that he existed.”