Obsessive fans organise to push Chinese idols to top of global hit parades

- Devotees dip into their own pockets to get their favourites to No 1.

- Multibillion-dollar ‘fan economy’ effectively a closed shop for non-Chinese.

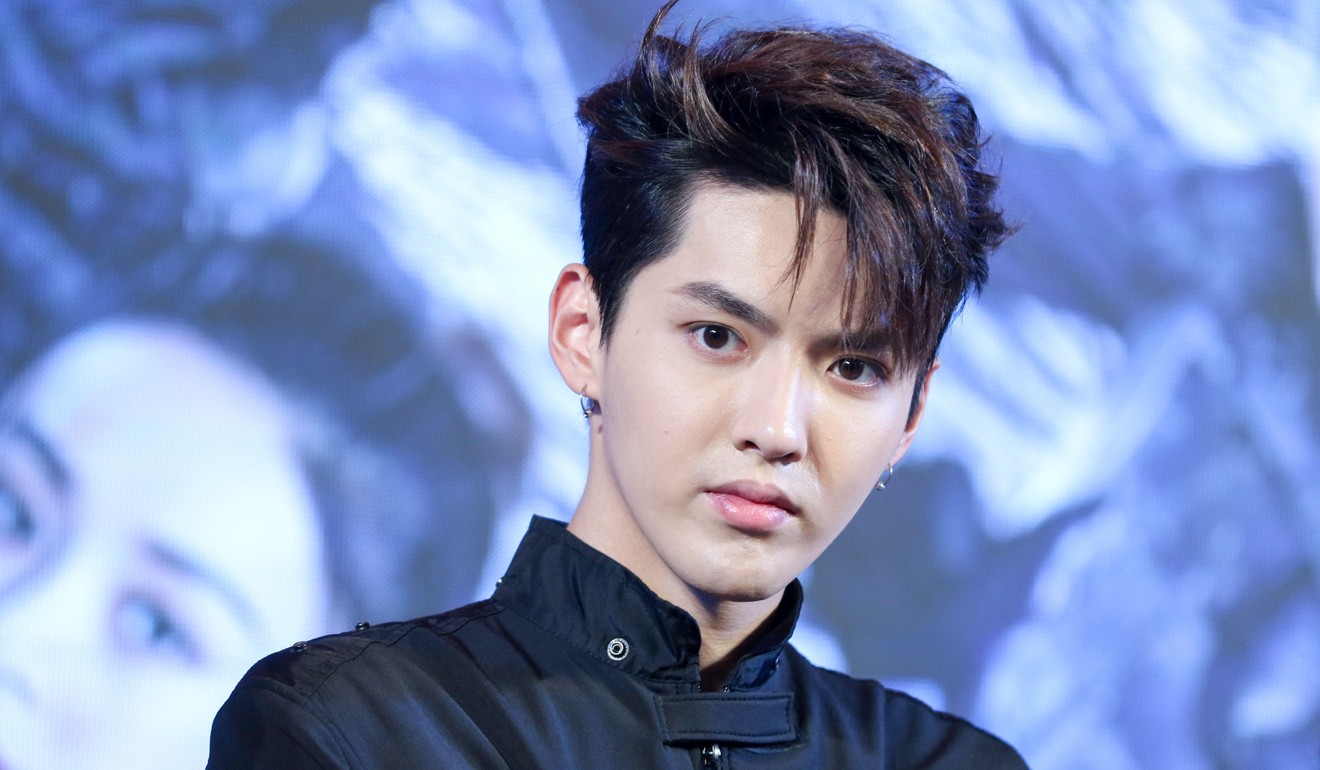

American pop star Ariana Grande had every reason to expect that her new single, Thank U, Next, would race to the top of the charts in the United States when it was released earlier this month. When she checked iTunes after its release, though, she met with a surprise. Kris Wu, a superstar in China, not only had the No 1 spot on the iTunes’ singles chart but also seven of the top 10 songs.

It was an extraordinary achievement for an artist with almost no North American profile, and Grande and her camp were not buying it. Rumours started flying on social media that “bots” were behind Wu’s chart dominance.

Sceptics were right about one thing: there was an organised effort to boost Wu’s sales. But it was organised by Chinese fans who spent their own money to push him up the US charts, not music promoters or programmers.

Fans of the Chinese boy band TFBoys have, among other activities, bought up the entire run (120,000 copies) of the Harper’s Bazaar magazine issue featuring a member on the cover, purchased billboards in Times Square, New York, to wish happy birthday to another member, and prepared custom textbooks for yet another member, when he was prepping for China’s college entrance exam.

The success of this multibillion-dollar “fan economy” has been so profound that Chinese brands are now actively trying to profit from it. Western companies looking to break into the mainland market would be wise to pay heed.

The origins of China’s fan economy – roughly defined as the value and revenue generated by the interactions between fans and stars – predates social media. In 2005, a scrappy provincial television station launched the Mengniu Yoghurt Super Girl Contest, an American Idol knock-off.

China’s online publishing industry – where fortune favours the few, and sometimes the undeserving

Viewers voted for their favourites via text messages (for which they paid) and, during the final episodes, formed fan clubs that campaigned for particular contestants. In Shanghai, the clubs canvassed shopping malls, subway stations, public parks and other public spaces in search of votes for performers.

What drove this intensity remains obscure. For many young Chinese, celebrity worship represents a rare opportunity to express support for lifestyles and backgrounds that are typically marginalised. It is perhaps no accident that many of the most prominent winners of Super Girl came from provincial backgrounds and were strikingly androgynous.

First, fans organised into clubs (the biggest celebrities enjoy the support of hundreds and even thousands of clubs), some of which were encouraged by celebrities and their managers. And second, stars and their handlers worked hard to make the fans feel that they had a role in shaping an artist’s career, thereby strengthening fan loyalty and engagement.

This fan influence can take several forms, from real-time back-and-forth in online forums, to launching go-fund-me-style campaigns to promote their favourite star’s latest project, to buying multiple copies of a new release. For many celebrities, turning fan-club members into subscribers is a natural and common process, especially for celebrity authors. One recent estimate predicts the value of such fan-economy interactions could exceed US$15 billion by 2020.

‘Post-90s’ generation dominates consumer spending in Singles’ Day 11.11 shopping festival

Of course, the phenomenon is not entirely innocent. Agencies exist to create fan bases and ensure that they are boosting a celebrity’s image. According to one recent report in Chinese media, “professional fans” who gin up enthusiasm, police online discussions and organise other fans can make more than US$4,000 per month in salaries and subsidies. According to that report, only 30 per cent of celebrity-fan interactions on Weibo, China’s Twitter-like social media site, comes from actual fans.

China’s ‘little fresh meat’ teen male heartthrobs milk their fame to sell fashion and beauty products to young women

Meanwhile, Chinese celebrities are increasingly using social media to sell products to their followers. The most notable example is Little Red Book, a so-called social-commerce app focused on fashion and beauty, where Chinese actress and Dior brand ambassador Angelababy recommends products to her more than 14.4 million followers.

Foreign celebrities and brands will struggle to compete with that kind of grassroots support. Kim Kardashian West, who joined Little Red Book in October, has a mere 105,000 followers interested in her English-language posts and US-centric career. Ariana Grande is not on the site at all.

Meanwhile, outside of Apple, no US-based brand has the kind of grassroots cult following in China that Xiaomi enjoys. Over time, perhaps they can overcome the cultural and linguistic barriers that prevent them from developing those kinds of followings in China. Until they do, foreign brands may find Chinese celebrity to be yet another frustrating trade barrier. Bloomberg