Thailand’s new Michelin guide: gold standard of restaurant reviews or overhyped and out-of-date?

- While some describe the French guide as the ultimate authority, bloggers claim Michelin lacks cutting-edge credibility

- Kingdom’s celebrated street-food stalls enjoy recognition alongside tried-and-tested eateries

Every day is different for Khun Gee, who works for an events company in Bangkok. Sometimes he is on the streets, sometimes he is in a mall. Today, he is in the ballroom of a five-star hotel off Ploenchit Road, his wire-thin frame costumed by the bulbous contours of a Michelin Man, aka Bibendum, aka Bib, aka Bibelobis.

The three-hour gig nets him 2,000 baht (HK$475). “At least there’s air-con in here, and I won’t get kids bumping me from behind,” he says. “Can’t say I’ve ever been to a Michelin restaurant, though.” Gee pauses, then grins. “There again, I might have eaten some of the street food they’ve awarded.”

Thai street food chef hailed by Michelin – what took them so long?

Gee’s piece of mummery is part of the ballyhoo surrounding the launch of the second Michelin guide to Thailand: 217 eateries, 67 hotels and a minor galaxy of stars strewn over Bangkok and – new for this edition – Phuket and Phang Nga. Rather than being a ho-hum press conference, it has been dubbed “A Revelation”.

The ballroom is packed with Michelin bigwigs, tourism-board honchos, assorted friends and relatives, and the sort of folk who are not displeased to find themselves labelled glitterati. A battery of television cameras and three outsize screens capture the action, and the speeches are larded with phrases such as “seasonal local produce” and “authentic culinary journey”. There are also discreet, almost subliminal references to the awards being “a driving force for tourism” and “fuelling industry growth”. Who’d have guessed that Michelin also manufactures car tyres?

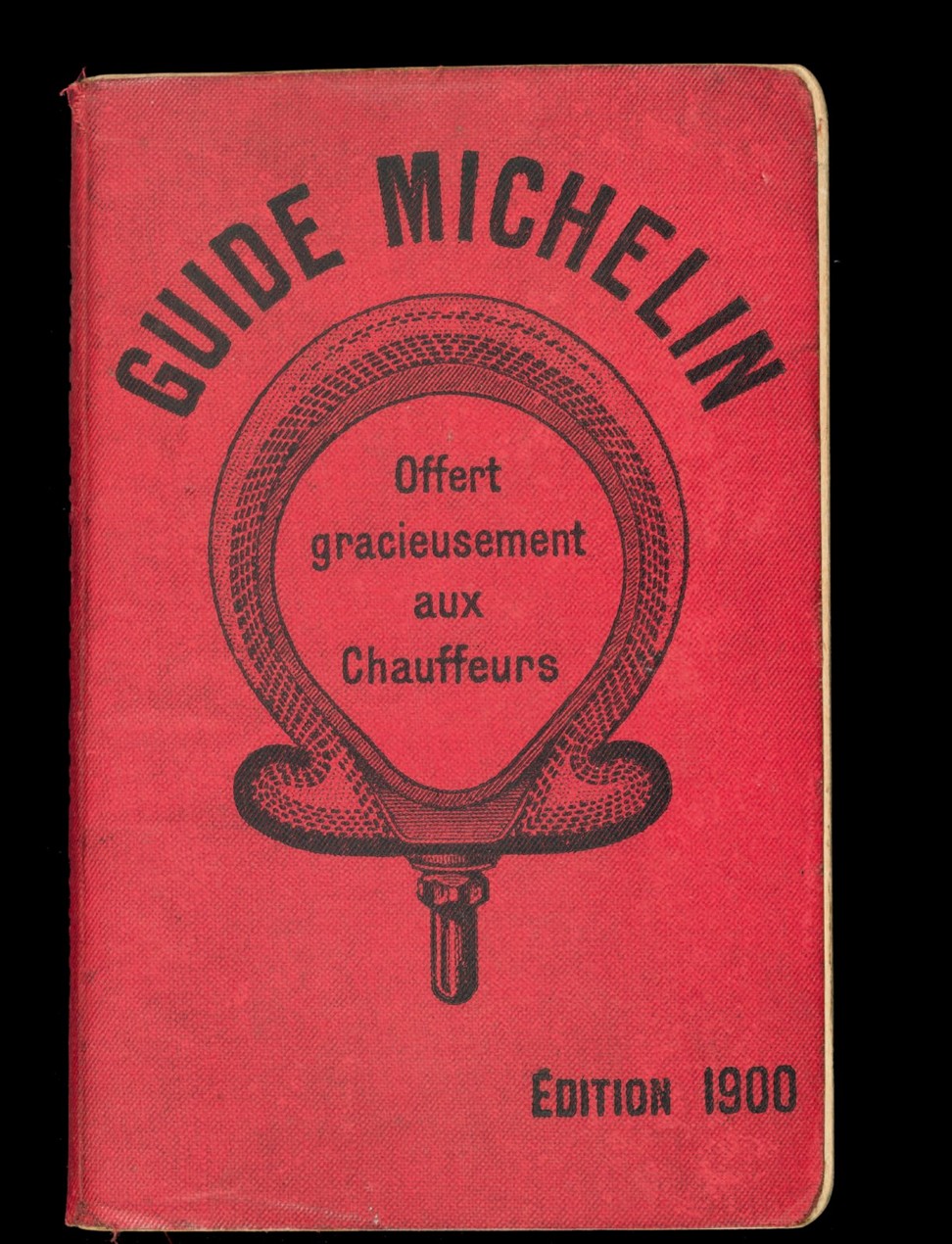

The first Michelin guide (“Offert gracieusement aux Chauffeurs”, or “offered free of charge to drivers”) was published in 1900 and was a how-to for France’s 3,000 fledgling motorists that pinpointed petrol stations, supplied tyre-changing instructions and – crucially – listed places to eat and stay overnight. At a time when no one had really got a handle on integrated marketing strategies, it was the original inspirational road map: go forth and wear out our tyres, and then buy some more.

Initially handed out willy-nilly, a price tag of seven francs was introduced from 1920, after company founder André Michelin had been horrified by the discovery of a copy propping up a garage workbench. (The current, bilingual Thailand edition retails for 650 baht, or US$20.)

Fast-forward a century and the Michelin guide has gained a far higher profile, although its auxiliary role remains that of garnishing the image of its tyre-manufacturing parent. Michelin’s rubber goods notched up a robust €16.2 billion (US$18.3 billion) in net sales in the first nine months of this year; net profits from January to June were tagged at €917 million, an increase of 6 per cent on 2017. Some analysts have suggested that researching, writing, editing, printing and distributing the guides worldwide may cost the company as much as HK$235 million (US$30 million) a year, though Michelin executives tend to adopt fixed grins when pressed on the matter. Still, many regard Michelin’s star-scattering as a pricey yet valuable form of advertising.

While the awards ceremony’s MC (boyish male model Pitipat Kootrakul) was almost drowned out by the gasps of admiration and fusillades of backslapping, news of Michelin’s most recent bestowals was met with more than a few pursed lips and raised eyebrows in some quarters across Thailand’s food scene.

There is no way one book can represent a whole country, especially in terms of food ... Frankly, as someone who lives in Bangkok, I see no point in referring to the book for food guidance

“First off, there is no way one book can represent a whole country, especially in terms of food,” says Sirin Wongpanit, who pilots Thai culinary blog OhHappyBear. com. “Besides, Phuket and Phang Nga deserve their own guide.

“Frankly, as someone who lives in Bangkok, I see no point in referring to the book for food guidance, though it might be useful for a time-poor visitor. What’s more, I think the Michelin guide is now facing a very difficult time to set itself apart in order to remain the ultimate arbiter of taste. With myriad foodies on Instagram and other platforms, people who are on the lookout for great new food might not need the Michelin guide at all.

“And when it comes to a French company putting out a book on Thai food, let’s just say I wouldn’t dare to comment on Chinese food unless I had some solid knowledge.”

Sirin reckons Michelin’s more humble awards – Bib Gourmand and Plate – are a more wholesome guide to local cuisine, but still slates the guide’s choice of mainstream restaurants. “The restaurants they picked are so media-fatigued that everyone has already heard of them,” she says. “Locals have moved on to the next best thing while Michelin hangs on to the safe and well-known.”

It is no secret, in fact, that Michelin’s select survey of Thai cuisine is heavily backed by the country’s tourism authority. While Michelin has been wary of publicising the precise figures involved, it is generally understood that the Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT) pledged 144 million baht to Michelin for the 2017-2021 period, the rationale being that the guide would boost visitor numbers.

Gwendal Poullennec, a slim, bearded Parisian with the earnest look of an ambitious university professor, who is international director of Michelin Guides, is quick to emphasise the guide’s probity. “The selection is absolutely independent,” he says. “We have a multinational team of inspectors, who always pay their own way and visit a restaurant not once or twice but as many times as it is necessary to reach a decision, which is never left to one person.

“We do not rely on funding for the ratings, no question about it.”

Our inspections are anonymous, and carried out with full confidentiality. We don’t share the results with anyone before D-Day

Asked if outside financing affected the guide’s credibility, Poullennec’s response is the antithesis of a Gallic shrug. “I really don’t think so. In fact, absolutely not,” he says. “Our inspections are anonymous, and carried out with full confidentiality. We don’t share the results with anyone before D-Day. The first that anyone from TAT knows about the contents of the guide is the very morning the results are made public.”

Yet across Asia, Michelin’s guides have come under increasing scrutiny. Last year, the Korea Tourism Organisation was criticised for handing over 2 billion won (HK$13.8 million) to support a guide to Seoul. In Hong Kong, funding for the most recent guide was bolstered by contributions from a slew of corporate sponsors, including Evian, Nespresso, Mercedes-AMG and a Macanese casino. And in Singapore, tourism officials have admitted facilitating “various business development discussions between Michelin and potential sponsors and partners” in the city. However, while all parties have been keen to stress that the reviews remain independent and unbiased, commentators – taking Singapore as an example – have pointed to “title sponsor” Resorts World Sentosa’s restaurants picking up four stars in the 2016 awards.

Of course, the world of travel – and food reviewing, in particular – has changed since Michelin was pretty much the only kid on a rather less busy block. And the glory days of obediently tucking napkins under chins as directed by Bibendum may well be numbered due to the wealth of other media jostling for eyeballs.

The United States-based World Food Travel Association is conducting a Food Travel Monitor study that is due to be released in 2020. Its last report, which examined what motivated travellers particularly in regards to food, found that nearly three-quarters of those they surveyed were most influenced by word-of-mouth recommendations, followed by review sites such as TripAdvisor. Celebrities and online influencers also commanded a distinct amount of attention. And more than a few observers have posed the delicate question: why buy a book that may have been researched months ago when I can get an online review from someone who was there just the other day?

Erik Wolf, the association’s executive director, noted, “As both a food lover and a traveller, I would not choose a destination by a list of top 50 or whatever. I would look at that list if I were already headed to that destination, but it wouldn’t influence my choice of destination.”

Back at the awards, while spectators barrack from the sidelines, chefs from the capital and the provinces slurp up their 15 minutes of fame and seem all too keen on second helpings. The gilding with Michelin stardust spells good news in the shape of both bragging rights and bottom line.

“Since my restaurant first appeared in the guide, we’ve seen a 15 per cent increase in custom,” says Arnaud Dunand-Sauthier, who helms two-star Le Normandie, at the Mandarin Oriental, Bangkok hotel, beside the Chao Phraya River. “I started work when I was 14 years old, and I’ve been in Thailand for six years, so this is a great honour.

“All sorts of reviews are open to travellers nowadays, be it TripAdvisor or Instagram or whatever, but the people writing them don’t really know that much about food or how to eat. With Michelin, you know that you are being reviewed by professionals, though you don’t know who they are. It’s the gold standard, no question.”

All sorts of reviews are open to travellers nowadays, be it TripAdvisor or Instagram or whatever, but the people writing them don’t really know that much about food or how to eat

For other bon viveurs in the City of Angels, the Michelin guide performs a dual role as milestone and bellwether.

“Thailand’s food and beverage scene has developed tremendously over the past several years, with much more variety and greater accessibility to higher quality ingredients and menus,” says Valent D. Soisuvarn, who, after a stint working in California, returned to his native Bangkok, where he now publishes the Thai edition of Playboy magazine. “The Michelin guide has brought an internationally recognised standard that will only help to highlight the amazing foods to be had in what was formerly a word-of-mouth culture.”

If stepping out of Bangkok was a brave move for Michelin, the choice of Phuket and Phang Nga was logical, as they continue to be two of the country’s most popular holiday spots. Other well-known destinations, such as Koh Samui, Krabi and Chiang Mai, as yet do not quite have the gourmet cachet of the west coast, however Michelin’s selection was fairly predictable.

Pru, part of Phuket’s super-luxury Trisara resort, was the only restaurant in the region to pick up a star (deservedly so for its eco-credentials and standards that outstrip anywhere else in the area). Otherwise, the guide covers mainly well-established restaurants, with a leavening of the sort of street food that is the icing on a pretty spicy cake. Twenty-nine plates and 14 bibs were handed out across Phuket and Phang Nga; contemporary Thai restaurant Suay, in Cherngtalay, an example of the former, pork and rice-noodle street stall Go-Benz a proud wearer of the latter.

Hollywood-approved lifestyle guru plays central role at Phuket resort

Western marketing totems are usually given a twist in Thailand, so the Colonel Sanders and Ronald McDonald mannequins outside their respective premises knit their hands into a respectful wai. Cavorting amid the award-winning chefs and applauding suits during the awards ceremony, Khun Gee – in his temporary persona as Monsieur Michelin – gives a determined thumbs-up, as if he was semaphoring: “As Oscars are to film, so Michelin is to food. We’re at the top now, and we aim to hang in there.”