Russian shipwreck and a South Korean crypto scam – how investors were fooled by promise of US$133 billion sunken treasure

- When the wreck of the Dmitrii Donskoi was supposedly discovered by a South Korean company, investors jumped aboard to get a share of US$133 billion of gold. The only problem? It has never materialised

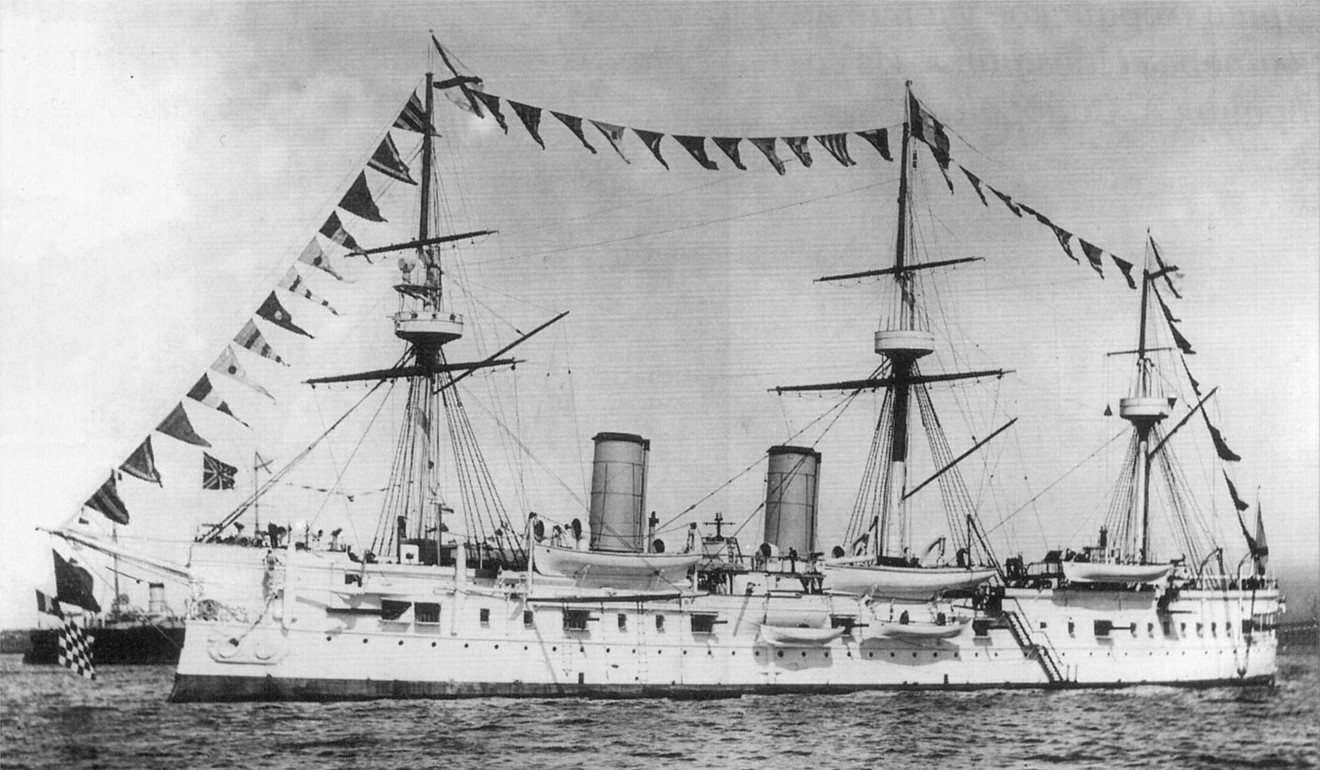

As Captain Ivan Lebedev stood on the bridge of the armoured cruiser Dmitrii Donskoi on May 29, 1905, and gave the order for his badly damaged ship to be scuttled, he could have had no idea of the financial scandal his command would cause some 113 years later.

The warship had been damaged by Japanese torpedo boats and destroyers in the Battle of Tsushima, which devastated the Russian fleet and effectively handed victory to Japan in the Russo-Japanese war. The conflict was waged over rival imperial ambitions in the Chinese-controlled territories of Manchuria and coastal Korea. Attempting to head north for Vladivostok after the battle, Lebedev intended to beach his crippled warship on the small Korean island of Ulleungdo but then decided to cast anchor, ferry his ship’s company ashore in small boats and sink her in the deep water, about 2km from the rugged coastline.

Found: ‘Holy Grail of shipwrecks’, with US$17 billion aboard

The Dmitrii Donskoi is now at the centre of a major treasure-hunting controversy being investigated by police in South Korea. The case confirms that, when it comes to investing in the salvaging of shipwrecks filled with lost treasure, the gullibility of some people can run as deep as any ocean.

At a press conference held by the Shinil Group in Seoul on July 26, underwater video footage was shown of Captain Lebedev’s ship. Shinil’s senior management claimed the company had discovered the wreck in 434 metres of water, off the coast of Ulleungdo. The company’s chief executive, Choe Yong-seok, described several tightly lashed boxes within the ship that, he said, appeared to carry “meaningful items”.

Choe added that Russian archive documents indicated they contained gold – and lots of it. Korean media reported rumours of gold bullion and coins estimated to be worth in the region of US$133 billion. Video stills provided to journalists showed remarkably clear images of the ship’s nameplate, illuminated in the gloomy depths, and the possibility was raised that the cargo was the reason Lebedev was so reluctant to beach his stricken vessel.

Korean media reports say Shinil convinced 2,600 investors to part with a small fortune in a cryptocurrency scam linked to the promised recovery of the gold. Police have frozen Shinil assets worth 2.4 billion won (US$2.1 million) and imposed a travel ban on 21 people involved in their investigation.

In October, two Shinil executives were arrested, says Park Si-soo, a reporter who has been following the case for The Korea Times, and “are suspected of having attracted 9 billion Korean won from investors with alleged fraudulent promotion of the value of the company’s cryptocurrency”.

The company had timed its announcement to coincide with the launch of its own cryptocurrency. Investors in Shinil Gold Coin would be reimbursed from the submersed treasure. Shinil, it seems, had tapped into cryptocurrency mania and combined it with the allure of shipwrecks and sunken treasure to create an attractive investment proposition.

Race for Russian warship’s ‘5,500 boxes of gold’ after wreck found

Though Shinil executives deny any wrongdoing and insist they still plan to salvage the wreck, the company’s website and telephone lines no longer work.

The case appears to have much in common with a classic shipwreck con. The first element of the scam is to find a wreck, and then compelling evidence (genuine or not) associating that wreck with treasure is produced.

Footage from remotely operated underwater vehicles is popular, but evidence can be as simple as a piece of ship’s timber. If the timber (perhaps pilfered from a museum) can be verified as being of the same age and type as the treasure ship being sought, it can be used to associate any shipwreck found on the seabed with treasure, and investors can be persuaded that there lies a large pay-off.

There are often warning signs in wreck scams, but they tend to be ignored. In one example, in the mid-1990s, investors were surprised to find the survey vessel commissioned for a sonar search was a luxury motor yacht crewed mostly by bikini-clad hostesses serving champagne. The hunt for a Spanish galleon off the coast of Florida turned out to be an elaborate fraud for which the project leader was eventually charged and imprisoned.

In Korea, Shinil’s claim about the shipwreck discovery has been disputed by the state-run Korea Institute of Ocean Science and Technology, which told media that it had discovered the wreck of the Dmitrii Donskoi in 2003.

According to one expert, even if Shinil were to recover the ship’s gold, keeping it would prove problematic. “First, it was a Russian warship, so even if in territorial waters of Korea, the [International Maritime Organisation’s] International Convention On Salvage excludes state-owned vessels, and Russia probably would have asserted ownership, as most flag states do for warships, especially if they thought there was gold on board,” says Professor Steven Gallagher, associate dean at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, who is researching cultural heritage law in Asia.

Even when considering investment in legitimate salvage projects, individuals should ask themselves a question, says Bill Jeffery, head of the Hong Kong Underwater Heritage Group: “Am I willing to risk thousands of dollars, maybe millions, to obtain material that I will never legally own and could be taken off me?” Jeffery adds that a number of court cases have shown that even artefacts that have been on the seabed for hundreds of years are still legally owned and looters have been forced to hand such material back.

Jeffery also raises an ethical issue for potential investors. “Am I happy to loot a graveyard? Many shipwrecks are scenes of terrible tragedies, like the Malaysian Airlines plane that is still missing,” he says. “Would you loot this plane for a few artefacts you can show your rich friends?”

Treasure hunting is a huge threat to underwater cultural heritage in Southeast Asia

Of course, not all treasure-hunting companies are unethical or dishonest. Established in 1994, Florida-based Odyssey Marine Exploration (Omex) is a world leader in deep-ocean exploration. The Nasdaq-listed company reports that in September 2011, in a salvage operation undertaken in partnership with the British government, Omex recovered 100 tonnes of silver cargo from the SS Gairsoppa, a merchant vessel sunk by a German U-boat in 1941 and located in deep water off Ireland. It was one of the largest recoveries from a shipwreck ever completed.

Yet even such well-established companies, with glowing credentials and glossy corporate profiles, have their detractors.

“Treasure hunting is a huge threat to underwater cultural heritage in Southeast Asia,” says Noel Hidalgo Tan, an archaeology expert at the Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organisation Regional Centre for Archaeology and Fine Arts, in Bangkok, Thailand. Many reputable auction houses will no longer handle shipwreck treasure, and museums have refused to put artefacts on display.

Perhaps the best known example is the Belitung shipwreck, also called the Tang shipwreck, a 9th-century Arabian dhow containing a cargo of some 60,000 items of Tang dynasty Chinese ceramics. The wreck was found by fishermen off Indonesia’s Belitung island in 1998 and salvaged by Seabed Explorations New Zealand with agreement from the Indonesian government.

In 2005, the recovered cargo was sold to a private company, the Sentosa Leisure Group, and the Singapore government for US$32 million and put on display in a purpose-built exhibition centre on the city state’s Sentosa island. Unfortunately, this attempt to celebrate underwater cultural heritage and Singapore’s place on the maritime Silk Road met with fierce opposition, notably from archaeologists. The Indonesian government was criticised for selling cultural heritage and Singapore’s Belitung collection was considered by some to be illicit loot.

In 2011, the Sackler Gallery, part of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, decided to cancel an exhibition of the collection due to doubts about whether the salvage had met with best practices and scientific standards.

And if such legal and ethical concerns are not enough of a deterrent, “investing in treasure hunting in a genuine company is a terrible idea from a profit perspective,” says heritage expert Natali Pearson, deputy director of the Sydney Southeast Asia Centre, Australia’s premier centre of interdisciplinary academic study of the region.

Pearson says that treasure hunting is usually characterised by huge investment for very limited return, and points to the case of Malaysian businessman Ong Soo Hin. In 1996, Ong teamed up with Vietnam’s National History Museum to excavate a wreck site off the coast of Hoi An, in Vietnam. The project took four years and cost an estimated US$14 million. More than 250,000 intact Vietnamese ceramic pieces were recovered, but Ong received only US$3 million at the subsequent auction.

400-year-old shipwreck off Portugal coast called ‘discovery of decade’

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (Unesco) introduced its Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage in 2001, to help prevent seabed looting. In a controversial 2016 briefing document, “The Impact of Treasure Hunting on Submerged Archaeological Sites”, Unesco accused Omex of intentionally overestimating the value of cargos to attract investment.

The same report includes a damning quote from investment analyst Ryan Morris, president of San Francisco-based Meson Capital Partners: “We believe the purpose of Omex (Odyssey Marine Exploration) is to serve as a vehicle for Omex insiders to live a life of glamour, hunting the ocean while disappointed investors foot the bill […] 100% of Omex’s 17 projects over 16 years were [financial] disappointments.”

According to its 2016 annual report, Omex made significant net losses in each financial year from 2012 to 2016, but when approached by Post Magazine, its spokesperson rejects both the Unesco accusations and the remarks of Morris, responding with a written statement that reads, “Since 1994, our team, led by world-renowned archaeologists and shipwreck explorers, has accomplished some of the most successful deep-ocean expeditions in the world, resulting in the discovery of hundreds of shipwrecks.” The statement accuses Morris of being a “known short-seller in the stock market” who, in 2013, attempted to depress Omex’s stock price with false reports.

“It is irresponsible for Unesco to quote a ‘businessman’ with a shady background,” the statement says, adding that, as a publicly traded company, all of Omex’s financial information is audited annually and reported on a quarterly basis. “In our company history we have never had any shareholder actions or legal claims against our company by investors.”

The Omex statement does not deny financial losses, but there can be no doubt that some treasure-hunting operations are extremely profitable.

Perhaps the most successful in Southeast Asia were undertaken by Michael Hatcher, the doyen of treasure hunters and nemesis of marine archaeologists. In the 80s, Hatcher salvaged what came to be known as the Nanking Cargo, from international waters near Indonesia, his team recovering more than 100,000 pieces of Chinese ceramics and 125 pure gold ingots from a Dutch East Indiaman that sank in the 1750s. More than 20,000 people attended the 1986 auction of the bounty in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, seduced by tales of adventure and Chinese treasure. In all, the sale fetched US$15.3 million, double pre-auction estimates.

Hatcher went on to salvage (or plunder, depending on your perspective) more wrecks. In 1999, he recovered the cargo of a large Chinese junk, the Tek Sing, that sank in 1822 between the port of Amoy (now Xiamen), in China, and Batavia (today Jakarta), in Indonesia. The tragedy took about 1,500 people – mostly Chinese immigrants – to the bottom of the sea.

This is one of the biggest challenges faced by the maritime archaeology community – the perpetuation of ideas that shipwreck cargo, which should be understood as part of the world’s underwater cultural heritage, [is instead] treasure

More than 350,000 pieces of porcelain were recovered by Hatcher’s team, and auctioned in Stuttgart, Germany, in 2000. According to Unesco, the cargo was an invaluable source of reference for early 19th-century Dehua blue-and-white porcelain, but the find was dispersed and the wreck destroyed. Chinese authorities were so horrified by what they regarded as the theft of national cultural heritage, they developed their own marine archaeology capability, and their skills are now considered among the best in the world.

It is widely accepted, in fact, that Hatcher was a catalyst for the development of professional marine archaeology in China, as well as for Unesco’s Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage. Hatcher’s well-publicised successes had fuelled the notion that shipwrecks were treasure troves just waiting to be exploited.

“This is one of the biggest challenges faced by the maritime archaeology community – the perpetuation of ideas that shipwreck cargo, which should be understood as part of the world’s underwater cultural heritage, [is instead] treasure,” says Pearson.

For those who still relish the idea of searching for sunken treasure, however, enticing opportunities remain out there.

American Tony Wells is an experienced commercial diver who has worked extensively on underwater projects in Southeast Asia, including the Flor de la Mar shipwreck, in the Strait of Malacca, in the late 80s. The project was eventually aborted due to legal disputes.

On his website, the Southeast Asian Treasure Connection, Wells details the so-called Golden Lily project, to salvage three Japanese shipwrecks off the coast of the Philippines. His first target is the wreck of a Japanese Navy heavy cruiser Wells says was scuttled on December 18, 1944, with a cargo of 200 tonnes of gold, worth about US$4 billion. He says half of this amount would have to be paid to the Philippine government as part of the licence conditions, leaving US$2 billion for him and his lucky investors.

The sunken gold is part of the well-documented Yamashita’s treasure, an alleged trove acquired by a Japanese general during a systematic plunder of banks, temples and private residences in Southeast Asia during the second world war. Most of the gold was supposedly secreted in caves and tunnels in the Philippines by retreating Japanese forces. Wells claims to have obtained details of the three Japanese vessels from a veteran American treasure hunter called Bob Curtis, who was part of a team recruited by Philippine president Ferdinand Marcos to find the Yamashita treasure in the 80s.

In 1992, Imelda Marcos claimed that her late husband’s fantastic wealth was based largely on the discovery of some of Yamashita’s gold.

Shipwreck found in sea bed off Wan Chai most likely famous Hong Kong ship HMS Tamar

“Bob Curtis gave me the exact water depth and general area where this first ship [with 200 metric tonnes of gold] was scuttled,” says Wells, by email. If found, the wreck would be accessible by remotely operated vehicle and divers, making the recovery operation relatively simple.

Wells reveals a credible and fully costed plan that involves three phases (search, identification and recovery). He says he intends to engage a reputable Hong Kong underwater survey contractor that uses advanced sonar technology for the first phase, which Wells estimates would cost US$5 million and take about 21 days. The total project cost runs to US$8 million and he says that, while he is not actively seeking investors, those few who have come forward to date are mostly “wishful thinkers”.

“It is not only about the money,” Wells says. “It is also about adventure and the possibility that such looted treasure exists – the thrill of the hunt.”

Nevertheless, potential investors might do well to heed an old stockbrokers’ saying: “The treasure hunter’s best sites are the investors’ pockets.”