Hong Kong has forgotten it owes its mango trees to Indian police and soldiers who first planted them

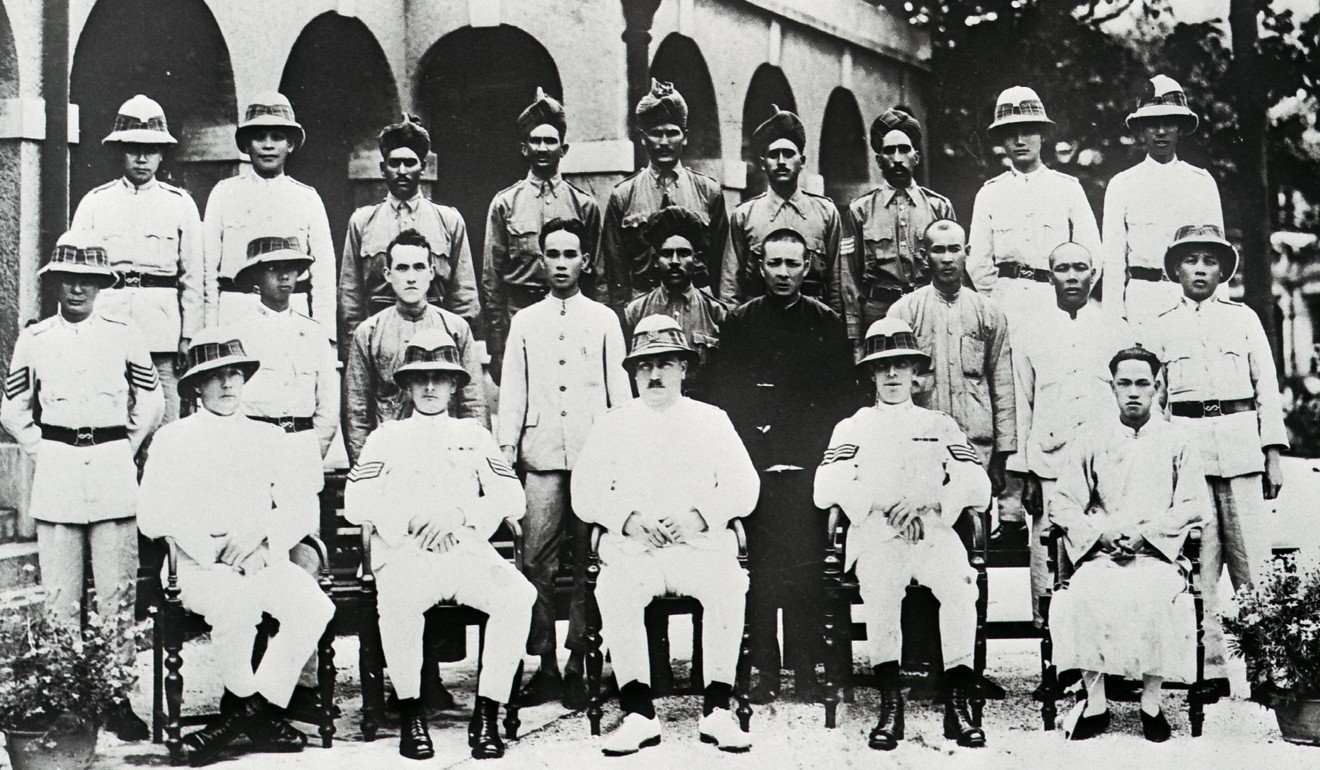

Across Hong Kong, mango trees grow. Though it’s rarely acknowledged nowadays, they owe their existence to Sikhs and Punjabis who came to the city to staff its uniformed services

About a decade ago in Hong Kong, as the Central Police Station adaptive reuse project gained traction, a local cultural body hosting a group of French architectural conservationists asked me to give a historical walk around the compound, accompanied by a couple of young curators from the government’s Antiquities and Monuments Office.

As I anticipated, when these well-intentioned functionaries twanged on interminably about the bricks, plasterwork, granite columns, floor tiles, iron drainpipes and such like, they made almost no impression on the visitors who – fresh from Paris – were visibly underwhelmed by the physical structure over which they were expected to gasp in rapt admiration.

Hong Kong’s colonial architecture more Calcutta and Macau than Britain

After half an hour or so of this tedious ramble, I cut in sharply, drew the group’s attention to the venerable mango tree in the courtyard and expanded upon exactly what made this towering botanical specimen possibly the most culturally interesting object in the complex.

Ignored by most visitors, that a a mango tree grew there in the first place gives us multilayered insights into Hong Kong’s multi-ethnic past. Mangoes are a cultural food from the Indian subcontinent; historically, these trees were seldom planted in southern China, as the climate is unsuitable for the fruit’s commercial production, and only what could be successfully cultivated was grown. Local tastes evolved, and cheaper refrigerated transport made this highly perishable imported fruit widely available in Hong Kong.

Within easy walking distance of Central Police Station, the Jamia Mosque also has several mature mango trees, and specimens can be found in Hong Kong Park (formerly the site of Victoria Barracks), the old Aberdeen Police Station, the Sikh Gurudwara on Queen’s Road East, and scattered around Kowloon Park (formerly the site of Whitfield Barracks). What do all these locations have in common? Sikh and Punjabi Muslim policemen or soldiers were once based there.

From the 1840s, people of both ethnicities came to Hong Kong in large numbers; once here, they planted mango seeds in and around their places of work, which – in time – grew, matured and produced fruit. A few slices of fresh ripe mango, or chutney made from the green ones, offered a welcome taste of home.

As soon as these connections were pointed out, the French conservators – who grasped the mango tree’s broader historical, cultural and culinary significance – became visibly enthusiastic for the first time, and a lively discussion followed. The local curators, in stark contrast, looked like they had been kicked in the solar plexus, and followed the dialogue with that blank-eyed, fixed-frozen half-smile so frequently encountered among Hong Kong officialdom, when they (mostly) understand the words being uttered, yet have no conceptual comprehension of the actual subject.

Changing face of Hong Kong is carved into its gravestones

Fast forward a decade and within the meticulously restored compound, a storyboard next to the mango tree labelled “Tai Kwun Tales” recounts: “Many officers believed that if the tree bore plenty of fruit, it would be a good year for promotion. Others thought that abundant fruit was a bad omen. This fruitless debate has continued for many decades.”

So here we see – after so much time, expense and effort – what masquerades as curated understanding of Hong Kong’s past; a gobbet of superstitious trivia wrapped around a pitifully lame pun, and the most unexpected aspect of the artefact airbrushed out of existence.

As I stood there a few weeks ago, relays of effervescent tour guides eddied around to parrot out their lines; not a single one – and I shadowed several to make sure – mentioned anything else about the mango tree. Plenty of empty space remains on the storyboard for more comprehensive information, in Chinese, English and – best of all – Urdu.

This last language would allow Hong Kong’s otherwise marginalised “ethnic minority” children to know that their great-grandfather’s lives here were honourably remembered, and not – as usual – shamefully and ignorantly erased.