How men became eunuchs to serve in imperial China’s Forbidden City

- An army of eunuchs was attached to the Forbidden City, primarily to safeguard the imperial women’s chastity

- Poverty, punishment and coercion were among the reasons why men ended up facing the ‘knifer’

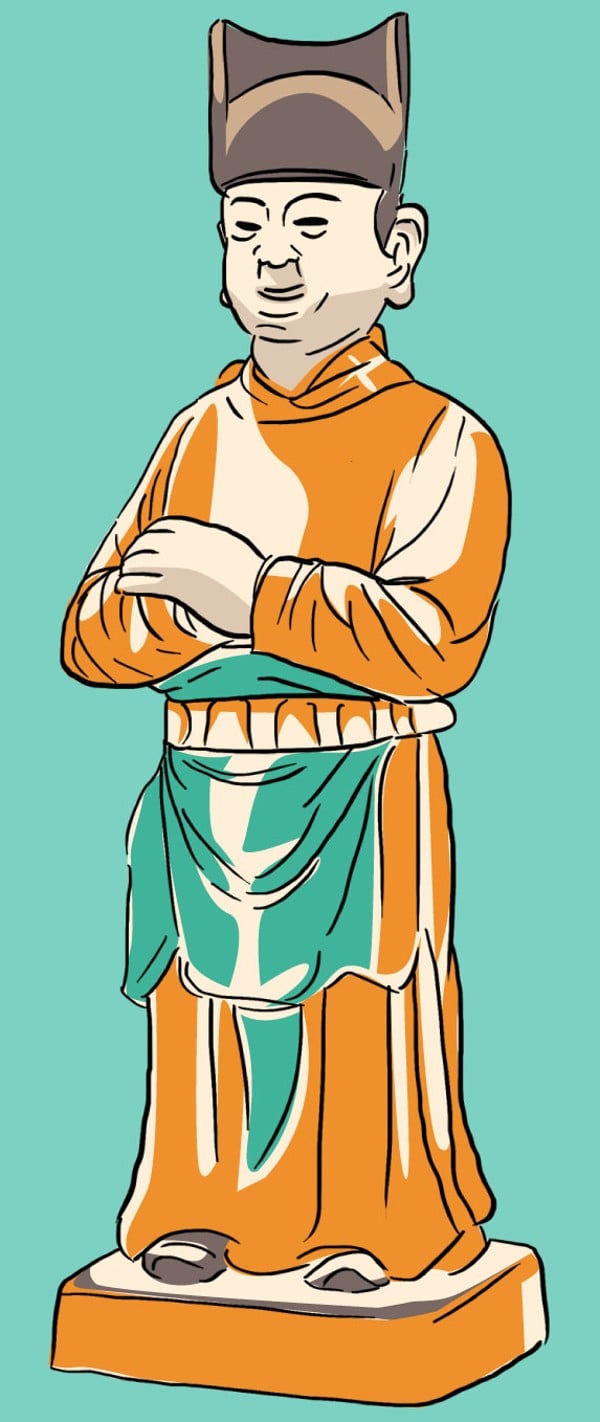

The presence of eunuchs in the Chinese court was a long-standing tradition. These emasculated men served as palace menials, spies and harem watchdogs throughout the ancient world. An army of eunuchs was attached to the Forbidden City, primarily to safeguard the imperial ladies’ chastity.

Confucian values deemed it vital for the emperor, seen as heaven’s representative on Earth, to produce a direct male heir to maintain harmony between heaven and Earth. Not wanting to leave anything to chance during a period with a high infant mortality rate, the world’s largest harem was placed at the emperor’s disposal to ensure enough heirs would survive into adulthood.

A 2,000-year system

Court chronicles record Chinese kings keeping emasculated servants in the eighth century BC, but historians generally date the appearance of eunuchs in court to the reign of Han Huan Di (AD146-167). The government role occupied by eunuchs meant that over time they were able to exert enough influence on emperors to gain control of state affairs and even cause the fall of some dynasties. The power of the eunuchs endured partly due to the ambitions of the consort families and partly as a result of the secluded lifestyle which etiquette prescribed for the emperor.

The eunuch system came to an end when it was abolished on November 5, 1924, when the last emperor, Puyi was driven out of the Forbidden City, where he had been living since the 1912 revolution.

Reasons boys and men would become eunuchs

Coercion: About an eighth of those who became eunuchs were young children bowing to parental pressure. Families would receive a cash reward for donating their sons, but they also hoped their children would have a more comfortable and prosperous life in the palace.

Poverty: Some adults, with no economic means to lead an honest and acceptable way of life, preferred emasculation to a life of begging and stealing.

Free choice: Some men, who could only envision a life of futility and hardship, were envious of the seemingly easy lifestyle enjoyed by palace eunuchs.

Punishment: Emperor Guangwu of Han (who reigned between 25 and 57BC) commuted all death sentences to emasculation. Successive emperors followed this edict.

Emasculation method

A small hut near the Forbidden City, called a ch’ang tzu, was used for the operations. A daozi jiang, or “knifer”, was responsible for the castrati throughout the process, including the healing stages.

He charged six taels (US$84) for the operation, and worked with several apprentices. The abdomen and upper thighs of the patient were tightly bound with bandages to prevent haemorrhaging.

The local anaesthetic during the late Qing dynasty was hot chilli sauce. The parts to be removed were disinfected by washing them three times in hot pepper water.

One man would separate the patient’s legs and hold him down firmly, so as to prevent any sudden movement. Two other men would hold him round the waist and pin down his arms.

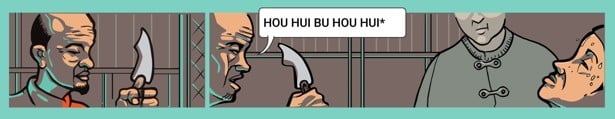

The surgeon would approach with a small, slightly curved blade in his hand. Facing the prospective eunuch, he would ask: “Will you regret it or not?”

If the man showed any doubt, the operation would be halted. But if he gave his consent, the knife was put to work. Both the scrotum and the penis were removed, generally with a single slash.

A pewter needle, or spigot, was carefully inserted into the main orifice at the root of the penis to prevent urethral stricture. The wound was carefully bound with paper that had been soaked in cold water.

After dressing the wound, assistants walked the eunuch around the room for three hours before letting him lie down. The spigot prevented the eunuch from urinating.

He would also suffer from extreme thirst because he was forbidden to drink for three days after the operation.

The spigot was removed after three days. The operation was deemed a success if urine flowed out. If no urine appeared, nothing could save the eunuch from a painful death. This happened in about 2 per cent of cases.

The wounds usually healed after 100 days. The new eunuch would then go to the imperial household to assume his duties.

Bao, or treasure

Bao translates as “the three preciouses” – the testicles and penis. The new eunuch’s bao was put into a container with a capacity of about 24 fluid ounces, sealed, and then placed on a high shelf.

The “precious” was kept for two reasons:

1. Every time a eunuch received an advance in rank he had to pass a strict examination. Promotion was impossible without the bao.

The examination process was called yan bao, and was lead by the head eunuch. The inspection was often a source of profit for knifers, because sometimes careless or ignorant eunuchs forgot to claim their “precious” after emasculation. They would then be forced to pay a high price to recover the bao. Bao were sometimes borrowed, purchased or rented.

2. When a eunuch died, he was buried with his bao. If he didn't have his own, he would try to obtain another before his death.

Eunuchs wanted to be as complete as possible when leaving this world because they believed they would have their masculinity restored in the afterlife. Tradition had it that Jun Wang, the king of the underworld, would turn those without their bao into a female mule. The ancient Chinese had a great fear of deformity.

Physical changes and appearance

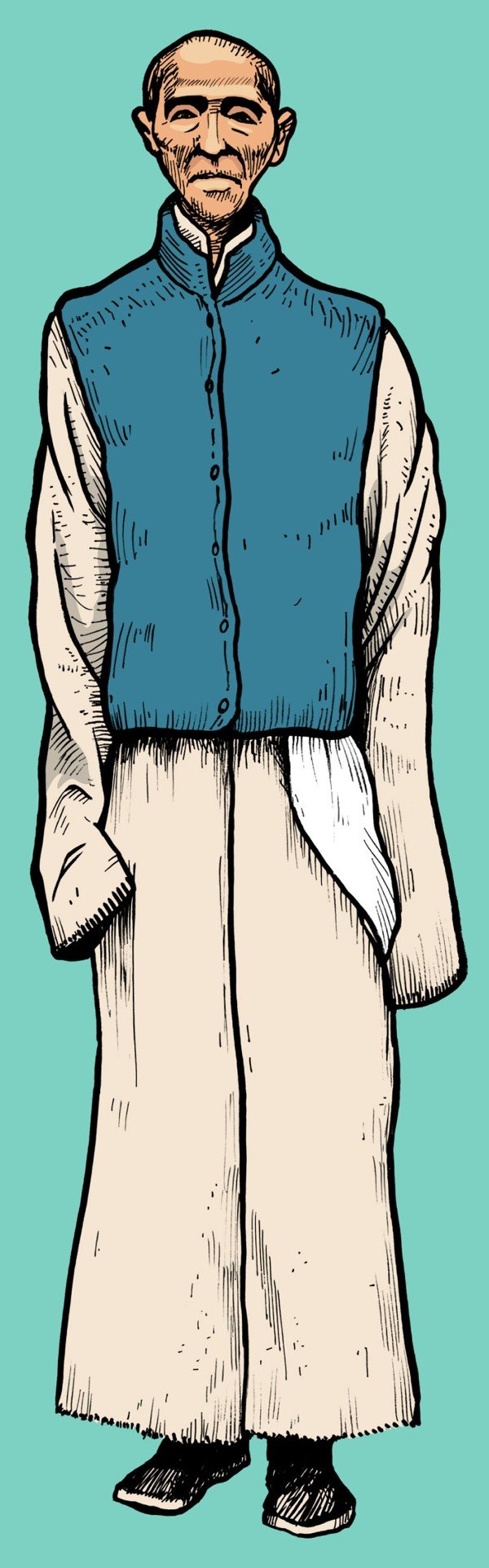

Emasculation cuts off the supply of male hormones to the body, leaving eunuchs with high voices. It also affected their bladder control, so they often wet their beds and clothes. This is the source of the old Chinese expression “as smelly as a eunuch”. They were also rendered too weak to perform strenuous physical activities.

According to G. Carter Stent, in his article “Chinese eunuchs”, published in 1877, emasculation affected character and could make eunuchs appear much older. They were vulnerable to bouts of extreme emotions, including moments of uncontrollable anger.

Beard growth stopped entirely. Eunuchs lost their natural voices – those who underwent the operation when they were children sounded like young women, while those who did so after arriving at maturity spoke in a cracked falsetto.

Those emasculated at an early age often put on weight; not so much as to be described as fat, but their flesh became soft and flaccid. They were physically weak and would become less fleshy as they aged.

Eunuchs took short steps and walked with a slightly forward inclination, with their toes pointing outwards. Their peculiar gait made them easy to recognise from a distance.