Is this just the beginning of ‘belt and road’ disputes between China and its partners?

As Beijing’s ambitious initiative turns five the time is ripe for business disagreements to arise

Be prepared to see a lot more business disputes on projects linked to China’s “Belt and Road Initiative”, warns Sarah Grimmer, secretary general of Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre (HKIAC).

Five years after Beijing rolled out its ambitious plan to improve regional and transcontinental connectivity, the time is ripe for disputes to arise as contracts mature, she said.

“Typically, we see a deal struck one year and, between two and five years later, that’s when we see disputes, so that’s when we start to see the cases come out of these transactions,” Grimmer said.

“So I expect that we will start to see disputes arising from the belt and road strategy around now. Over the next five to 10 years, we will see a lot more, and then it will continue. I think we are just at the beginning of the dispute phase.”

China’s biggest builders are sure that Xi Jinping can help them get Malaysia contracts back on track

The ambitious plan proposed by Chinese President Xi Jinping covers more than 65 countries from Asia, Africa and Europe and accounts for 30 per cent of global gross domestic product and more than 60 per cent of the world’s population. Estimates of funding for these projects range from US$1 trillion to US$8 trillion.

So far infrastructure projects are the mainstay of the initiative but the grand vision includes trade, transport, and even cultural and people-to-people exchanges.

In the run up to its fifth anniversary this month, the initiative has faced various setbacks, from the withdrawal of contracts to reassessment of costs, sometimes due to changes of government in participating countries.

The latest example was the cancellation of several mega projects in Malaysia after Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad retook power. Earlier, China’s ally Pakistan said it would re-examine and renegotiate the costs of Chinese funded projects in the US$62 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor.

Myanmar also sharply reduced costs for the Chinese-backed Kyaukpyu deep water port on its western coast.

Grimmer believes the trend will continue and warns about the huge potential financial fallout for Chinese companies.

“We will continue to see this around the region because we do have lots of jurisdictions where this can happen – the government changes and then the deal changes,” she said.

“The fallout from those decisions is massive. For the Chinese companies, the loss could be significant,” Grimmer said, citing the port city project dubbed Sri Lanka’s “new Dubai”. The Chinese investors carried the losses incurred when the project was suspended pending environmental assessment.

“I do think those kind of issues could happen again, given the nature of the projects and also given the nature of the countries with which we are dealing,” Grimmer said.

Challenges on China’s belt and road are real and many, and they point to a role for Hong Kong

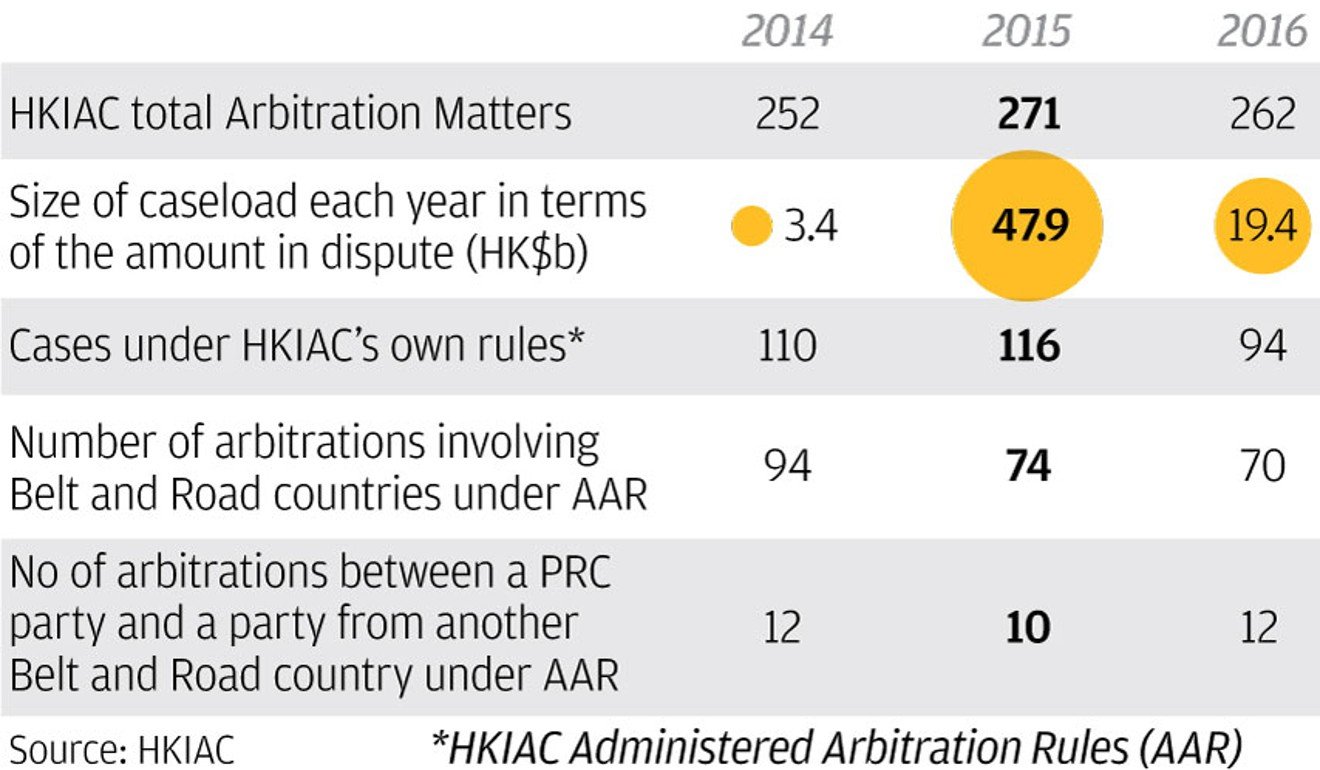

According to figures provided by the HKIAC, the number of arbitrations involving parties from countries participating in the initiative rose to 124 last year from 70 in 2016, while those between Chinese companies and parties to belt and road projects rose to 38 last year from 12 in 2016.

Grimmer said that in the past Chinese companies tended to be the respondents, but the number of Chinese claimants had risen in recent years, although it was hard to determine just how many were due to belt and road projects.

Arbitration clauses are becoming more common in contracts for cross border projects, with Hong Kong set to benefit.

“We understand anecdotally that a lot of negotiations may start with the Chinese parties saying, we will seek our arbitration in Beijing. The other side says no, we will go to London, for example. The compromise is Hong Kong,” she said.

Grimmer said the HKIAC so far had not taken on a case involving a belt and road infrastructure project.

“On our caseloads, there are not yet any cases arising out of the well known public disputes which have arisen when belt and road projects have gone wrong,” she said.

“We do have disputes arising out of contracts in jurisdictions taking part in the belt and road. We have big projects or projects involving tourists, complexes such as hotel arrangements, luxury residential and entertainment projects, and trade cases involving minerals such as iron ores that may be feeding into belt and road initiatives.”

Courts were set up in July in Xian, capital of northwest China’s Shaanxi province, and Shenzhen, southern Guangdong province, to handle international business disputes arising from belt and road projects.

The latter specialises in projects along the Maritime Silk Road, an aspect of the initiative that covers countries from Southeast Asia all the way to the Arabian peninsula and Africa.

How negotiations gave Myanmar and China both a better deal in joint port project

Grimmer said these courts did not have a track record and were not considered competitors to the HKIAC.

“The Chinese International Commercial Court is a new thing, it has not yet been tested. I do think it is a positive thing that this is another option for parties, and it may be a very good option in some instances. But we just don’t yet know, it hasn’t been tested.”

Foreign partners in joint ventures with Chinese parties may also be reluctant to have arbitration handled in mainland China, she said.

Instead, competition with Singapore, the region’s other major arbitration centre, was real. Hong Kong had decades of experience in dispute resolution while Singapore has strong backing by the government.

Grimmer said there was a “misunderstanding” about Hong Kong’s legal system in the eyes of some foreign companies, and it was important for the city to retain its reputation for judicial independence to give companies the confidence to choose it for arbitration.

“It is important for Hong Kong, as a commercial arbitration and dispute resolution centre, that its judiciary remains independent and untarnished,” she said.