Man from Pakistan spent almost 20 years unaware how sick he was – because he didn’t realise Hong Kong public hospitals provide interpreters

- Many patients who know little English or Chinese are left in the dark about their diagnoses because they don’t know interpreters are available

- A move to give patients the initiative in booking interpreters aims to make better use of the service, which hospital staff often decline to call on

For almost two decades, Ali (not his real name) was never clear about how ill he was or how he had been treated, despite regular follow-ups in hospitals.

An Urdu-speaker with little English or Chinese, the security guard, 44, was unaware Hong Kong’s public hospitals provide interpretation services for free.

The turning point came in January 2017, when Ali fainted at work and was rushed to Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Yau Ma Tei.

He had no idea what examinations he went through or what the results were. He was simply told he had “blood sugar”.

An NGO contacted hospital staff for translation, but an interpreter did not come until the last day of his stay. Ali said the nurses were not keen to book the service, saying it sufficed he could speak simple English.

“I felt helpless,” says Ali, who was diagnosed with diabetes and heart problems.

“In the first few days, I reflected on my poor education and how I couldn’t speak English very well. I wanted to say so many things but I couldn’t.”

Ali, who came to Hong Kong from Pakistan in 1994, is one of 584,000 people from ethnic minorities who make up 8 per cent of the city’s population.

According to an estimate by the Kowloon Diocesan Pastoral Centre for Workers, the NGO that helped Ali, about half of those cannot speak proficient English or Chinese and may need help.

The Hospital Authority which runs the city’s public hospitals and outpatient clinics, pays a non-profit group to provide interpretation, but bookings must be made by medical staff rather than by patients themselves.

It’s a patient’s right to know all their conditions. It is important for them to know their diagnosis, examinations, treatments and potential side effects of the treatments

The centre says a bureaucratic booking system and medical workers’ reluctance to help has left many patients in the dark about their illnesses.

Yet an unpublicised, small-scale pilot project by the authority on patient-led booking, which the Post has gained a sneak peek of, may offer a glimmer of hope.

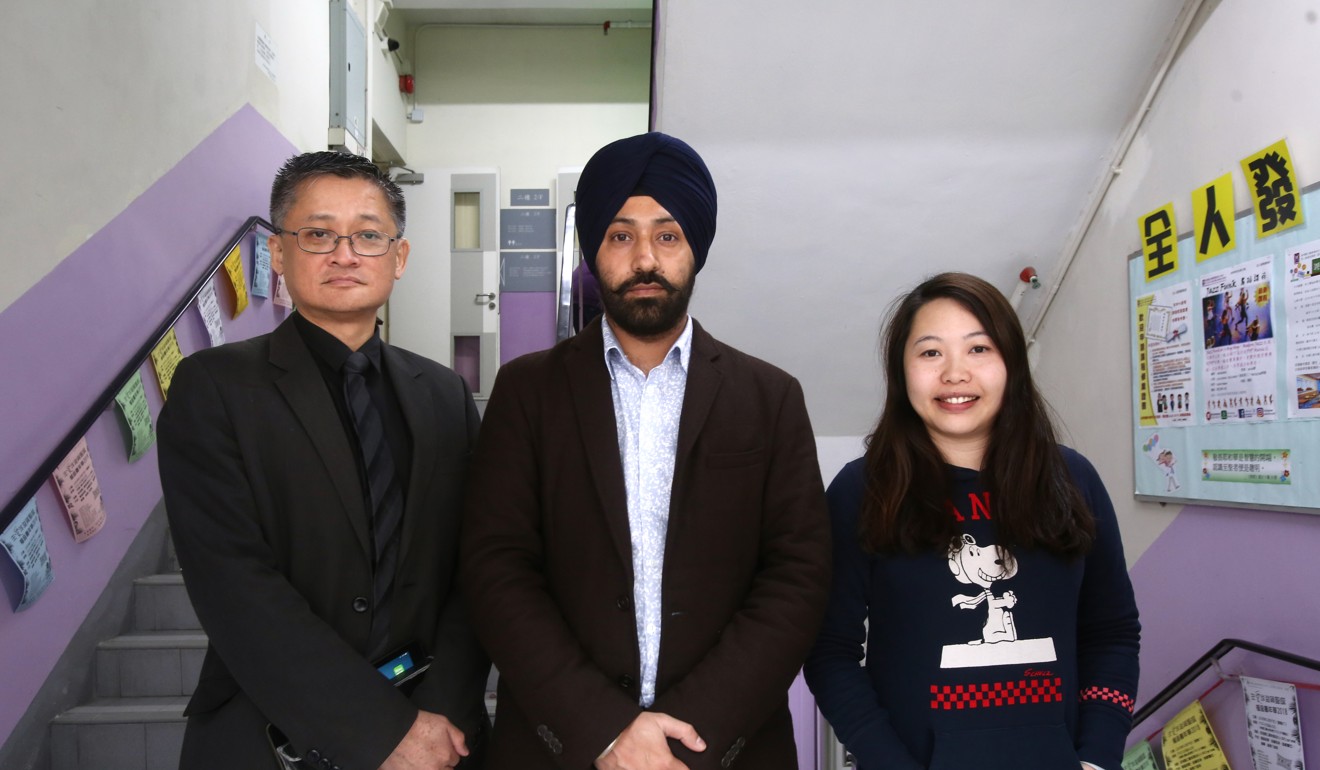

“It’s a patient’s right to know all their conditions,” says Shoaib Hussain, assistant programme officer at the centre, which specialises in liaising with medical staff on interpretation.

“It is important for them to know their diagnosis, examinations, treatments and potential side effects.”

Hussain and fellow assistant programme officer Sairah Abbas say the centre receives between 80 and 100 requests for help with hospital interpretation a year.

Such requests are often from middle-aged and elderly members of ethnic minorities, who have little education and little language support in Hong Kong.

Many are housewives who have few chances to interact with locals.

Hussain and Abbas say some nurses use the cost of the interpretation service – paid by the hour – as a reason to turn down requests, or they claim the patients’ basic English or Chinese is enough for doctors to understand them.

An authority spokesman did not respond to inquiries about the hourly charges for interpretation but in 2017-18, the authority spent HK$8.6 million over 15,257 cases – about HK$564 per case.

Hussain and Abbas say staff sometimes asked patients to bring family members with better language skills to help or asked fellow ethnic minority patients in the same ward to help.

Few books for inmates who read neither Chinese nor English

In one case, Abbas says, a lady suffering from gynaecological issues walked out of an emergency ward in embarrassment without seeing a doctor, after a nurse asked a Pakistani man – a complete stranger – to interpret.

“It’s a government-led booking system, not patient-led, and the process has not been normalised in hospitals,” Hussain says. “It hasn’t been part of hospital workers’ daily duties.”

Ali has suffered from chest pain, back pain, dizziness and blurry vision since 1998 without knowing details of his conditions.

He contacted the centre on the third of his eight-day stay in hospital in 2017 “out of desperation”, and the centre immediately called both Queen Elizabeth and the authority’s contracted interpretation provider. The provider said it could only act at the hospital’s request, while the hospital declined to help.

The next day, Hussain and a social worker visited the hospital to press the matter. After much negotiation, nurses agreed to help, but the interpreter did not come until the last day of Ali’s stay.

How Hong Kong can do more for job-seeking ethnic-minority residents

“It could be arranged within hours, but the hospital kept ignoring us,” Hussain says.

In general outpatient clinics, bureaucracy in the booking system is also abundant.

Patients must make phone appointments through a pre-recorded system with only English or Chinese language options, so a patient with language barriers would need help.

The phone system does not allow for booking an interpreter, so the patient would have to make a separate request for that.

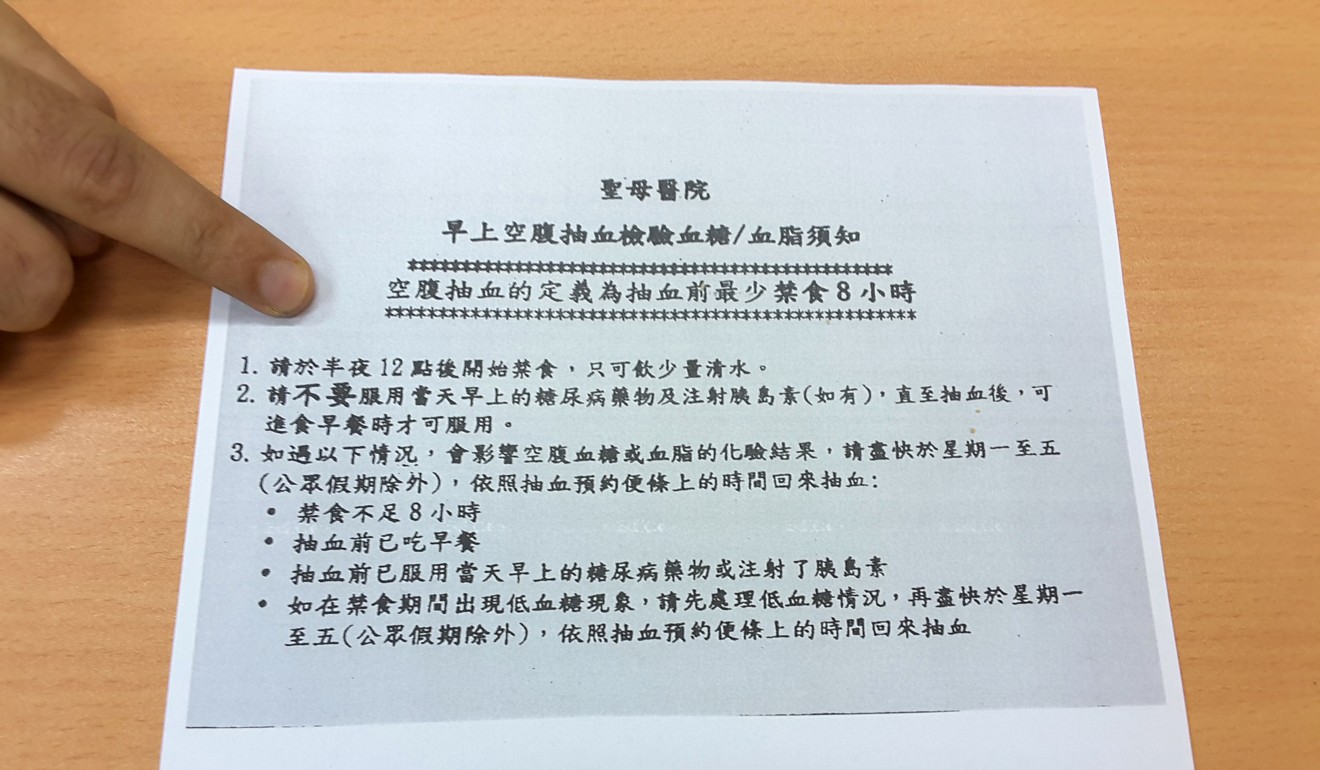

Not only is the booking system lacklustre, some hospitals do not translate essential notes into different languages, Hussain says.

One patient, due to take a blood test, was issued a note in Chinese requiring him to fast and omit diabetic drugs beforehand. After he complained, his doctor wrote an English version, which he also could not read.

In most cases, frontline workers have no knowledge of the system, says Jonathan Chan Ching-wa, senior service coordinator at SKH Lady MacLehose Centre, the authority’s contracted interpretation provider.

In some cases, family members, such as their children with better language skills, are the easiest to find and the fastest to arrive

“I have never seen any instances of deliberate refusal,” Chan says, adding the authority’s policy was staff should make bookings when patients required it, and even if patients did not, workers should ask them whether they needed interpretation.

“This is not for the staff to judge at all,” he says.

He recognises there would always be workers unaware of the booking system.

One of the worst cases he encountered, Chan says, was when the centre received a complaint from a patient about booking.

The centre called the hospital and asked the workers to book, but they did not believe there was such a system. Eventually the centre had to call authority superiors to explain.

“When you encounter refusals, tell us,” Chan says. “If you tell us … we can contact the hospital and check if there has been any misunderstanding.”

The authority spokesman says the medical employees arrange on-site or telephone interpretation through its contractor’s 24-hour hotline, and the authority provides training through an e-learning centre, internal publications, working groups, courses and talks.

He says one advantage of employee-led booking is members of staff can do it in a coordinated manner. When the contractor cannot provide interpreters, employees can attempt alternatives such as rescheduling patients’ appointment or arranging part-time interpreters.

‘New measures’ on way to help Hong Kong’s ethnic minority residents

Cecilia So Chui-kuen, president of the Hong Kong Nurses General Union, says medical staff considered speed more important than anything in emergencies, but it often takes several hours to arrange an interpreter.

“In some cases, family members, such as children with better language skills, are the easiest to find and the fastest to arrive,” So says. “And patients may feel it easier to talk to them than strangers.”

She adds that if X-ray or similar examinations are required, doctors might only need to know whether patients have had any accidents and how the accidents happened, where basic language skills would suffice.

The purpose of the trial is to test out a user-friendly workflow for ethnic minority patients booking interpretation service on their own

Chan also urges the authority to set up small, hospital-based interpreter teams to handle daily cases, while the centre’s mobile interpreters remain on call.

On the phone booking system for clinics, Chan notes difficulties in improvement. He points out the centre provides support in 19 languages, but it would be “very cumbersome” to include that many in a pre-recorded phone system.

An online booking system might also be inefficient, he says, because it requires internet access and language reading skills.

More language support urged for Hong Kong’s ethnic minority women

“More than half the people in one of the largest ethnic minority groups in Hong Kong in need of interpretation cannot read or write their mother tongue,” he says.

He believes an ideal phone system should involve human operators and artificial intelligence technology, which could determine what language the patients spoke and which operators to connect in the first 10 to 20 seconds.

Ali, whose own ordeal in understanding his medical conditions has led him to ponder the importance of learning a language, urges the government to provide more education support for ethnic minorities.

He also wishes to see more public funding to support all government departments and NGOs like Hussain’s group in hiring more ethnic minority staff members.

For him, all is not lost. Since he found out about the hospital interpretation service, he has been requesting it for his follow-ups.

“I encourage our children to have more education, so they will not be in the same situation that I faced any more,” he says.