Is reclamation the way to regain control of Hong Kong’s land supply from developers?

- In the third and last part of a series on land reclamation, the Post looks at whether developers are dominating land supply

- Questions raised over whether government should build up land reserve

In three weeks, Hong Kong’s town planners will scrutinise a huge private housing project in Sai Kung where a developer is seeking to double the number of units to 9,500 flats – more than the government could contribute last year in terms of land supply for such purposes.

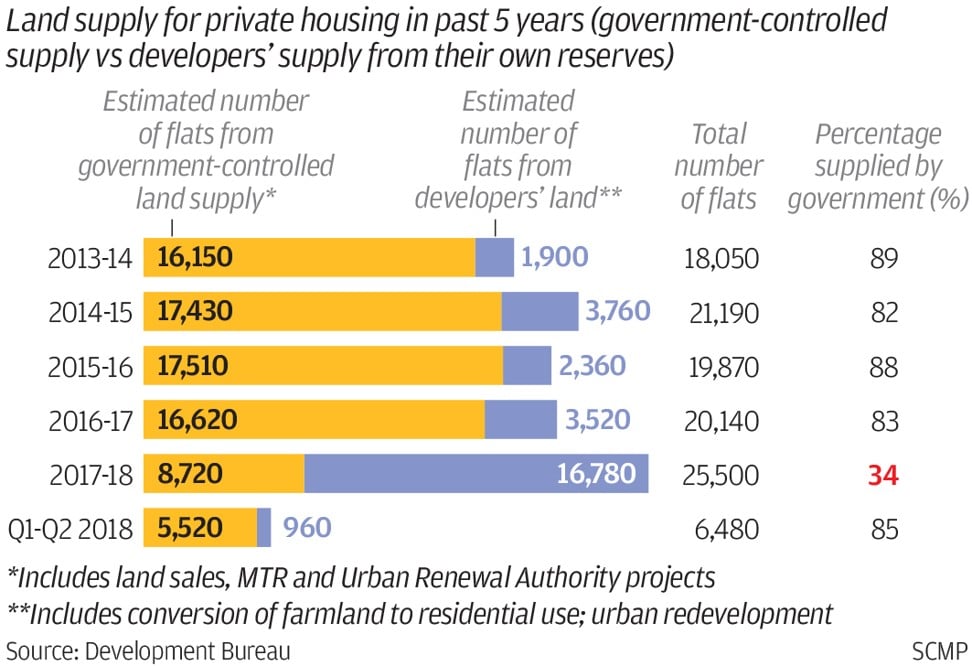

The project, and others by the private sector involving farmland conversion or redevelopment, amounted to 66 per cent of the annual total land supply for 25,500 private flats last year.

In the past, government-controlled land sources, including land sales, projects along rail lines and those under the Urban Renewal Authority, accounted for more than 80 per cent of the total number of private flats projected each year.

Some people have been alarmed in recent years by what they saw as a reliance on developers for land to build private homes. Concerns centre on companies holding too much land in a space-starved city, in turn allowing them excessive power over the private market.

Is Hong Kong ready to splash HK$500 billion (or more) on reclamation?

A government-appointed task force on land supply is expected to address the matter in a final report due later this month. All eyes are on what it will reveal about public views on reclamation – particularly on the creation of a massive artificial land mass off Lantau Island – among other options.

Dubbed the Lantau Tomorrow Vision by Lam, the 1,700-hectare development is billed as a new economic and residential hub for Hong Kong.

Think tank Our Hong Kong Foundation, which champions the project and had in August floated a similar idea, argued the government should “seize back” control from developers. The foundation’s research also stated land supply was increasingly “concentrated” in the hands of a few major players.

Island residents warn against Lantau reclamation, fearing ‘sins for a thousand years’

The group pointed out that this was worrying because when the government no longer had enough land to sell and had to rely on developers, supply would drop, driving up prices, and the timetable for available homes would become uncertain.

Developers then had the power to decide when they wanted to develop their reserves, and it could take up to a decade to turn damaged farmland, often unconnected to roads and amenities, into sites ready for development.

Lee Wing-tat, a former lawmaker who now leads research group Land Watch, agreed there might be a change in power between the government and developers if authorities could fall back on a land bank.

“Now developers know the government doesn’t have many bullets in its pocket,” Lee said. “They can be difficult to deal with in negotiations, and the process could drag on, slowing down supply.”

Now developers know the government doesn’t have many bullets in its pocket

But Lau Chun-kong, chairman of the Institute of Surveyors’ land policy panel, said the balance between the government and developers over land supply last year was uncommon because a massive project like Shap Sze Heung was rare.

The next project of this scale would be Yau Tong Bay, which would yield 6,000 homes on the former industrial site, but after that the market “would have to wait for some years” for another boom of this nature from the private sector, Lau added.

Ling Kar-kan, who retired as director of planning in 2016, agreed on the need for the government to build a land bank through reclamation and redeveloping brownfield sites or damaged agricultural plots.

“We should not be so short-sighted as to focus on real estate only,” Ling said. “The government also needs to make sure enough land is provided for different policy needs. The market will not take the initiative to address this.”

Lam to press ahead with reclamation, whether public likes it or not

He added that with a land reserve, authorities could effectively regulate operators of much-needed facilities such as hospitals, retirement homes and international schools by inserting conditions into the land grants.

An official planning study, Hong Kong 2030+, has identified “government, institution and community” (GIC) zones as the most pressing land use in the coming three decades.

The market will not take the initiative to address [land for policy needs]

The shortage of GIC sites – 720 hectares – is even higher than the 230-hectare housing shortfall. Even then, officials have been criticised for underestimating demand, and adjustments are being made.

Stewart Leung Chi-kin, chairman of the Real Estate Developers Association executive committee, said developers supported reclamation. “The government can sell land more cheaply when it has plenty. That’s good for people’s livelihood,” he said.

But, Land Watch’s Lee said reclamation should not be seen as the only option. Authorities could invoke the Lands Resumption Ordinance to take back farmland from developers.

“The resumption of land is not as much of a legal trouble as officials have said,” he added, citing the administration’s reply to a question filed by a lawmaker this year.

Since 1997, the government has invoked the ordinance to resume private land for 150 projects, of which 70 projects were for public housing, urban redevelopment and new towns. Only eight judicial review cases were lodged by landowners, with cases spending between one month and 12 months in court.

Peter Cookson Smith, an urban planner who has 40 years of experience in Hong Kong, said massive reclamation was not necessary or desirable because of a slowdown in population growth.

He said resources should be focused on committing to, and pushing ahead with, new town projects in the New Territories, which would adequately address the city’s thirst for land.