British Foreign Office was told to size up the risk of Chinese takeover of Hong Kong ahead of 1997, archives show

- Hong Kong governor Chris Patten reported to London in 1993 that the PLA’s Guangzhou military command had been tasked with drawing up contingency plans

- Former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping had previously made the threat that China might take the city in a 1982 meeting with Margaret Thatcher

The British Foreign Office was told to assess the risk of a possible military intervention by Beijing to retake Hong Kong before 1997, newly declassified British files have revealed.

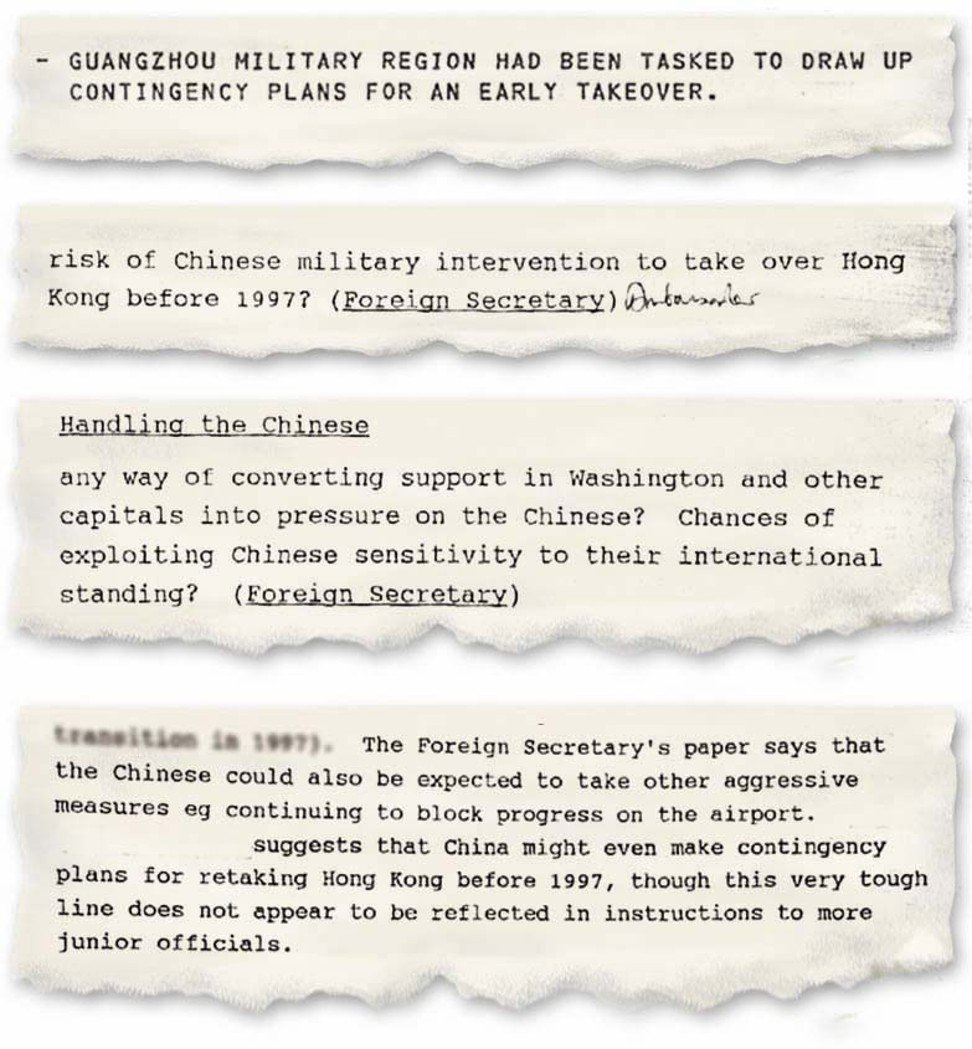

The call came as China ramped up attacks on the city’s last governor, Chris Patten, after he unveiled an electoral reform package which saw Beijing call him a “sinner for 1,000 years”. Patten reported to London in January 1993 the PLA’s Guangzhou military command had been tasked with drawing up contingency plans for an early takeover of the then British colony.

Patten’s proposal to give 2.7 million Hong Kong residents the vote, unveiled in his maiden policy address in October 1992, had angered Beijing. The British government’s fear of a military takeover of Hong Kong before the expiry of the lease of much of the city’s territory in 1997 and its contingency plan for the worst-case scenario were documented in the files newly released by the National Archives in London.

In a briefing paper for British prime minister John Major a day before the meeting of the defence and overseas policy committee under the cabinet, Pauline Neville-Jones, head of the defence and overseas secretariat in the cabinet office wrote that even if Patten’s assessment was that Hong Kong’s Legislative Council would eventually support his proposals, the committee would need to consider what to do if the situation worsened subsequently.

“If endorsement by Legco looks uncertain should the governor stage an orderly retreat, or risk being voted down?” she wrote.

“The meeting will need to address the fundamental issue of whether they should be carried forward despite the Chinese reaction,” Neville-Jones wrote. “The stakes are high and this is the point of no return.”

The meeting on November 18, 1992, chaired by Major, was attended by Britain’s top officials including the foreign secretary, home secretary, defence secretary, the chancellor of the exchequer, as well as Patten. But the outcome of the top-level meeting was not mentioned in the newly released files.

Neville-Jones cited papers submitted earlier by the foreign secretary stating that the Chinese government could be expected to take other aggressive measures.

“[Name redacted] suggests that China might even make contingency plans for retaking Hong Kong before 1997, though this very tough line does not appear to be reflected in instructions to more junior officials,” she wrote.

Margaret Thatcher’s 1982 Hong Kong visit revealed little about colony’s return to Chinese sovereignty

The committee needed to consider the risk of China’s military intervention to take over Hong Kong before 1997, she added, and foreign secretary Douglas Hurd was tasked with the assessment.

Under Patten’s electoral reform package, 2.7 million electors would be given a vote in nine new functional constituencies in the 1995 Legislative Council election. Ten lawmakers would be drawn from elected representatives of district boards, which were renamed as district councils after 1997.

Beijing believed it breached the Basic Law – the city’s mini-constitution – and Sino-British agreements already in place.

The British government gave its full backing to Patten’s proposal. It was eventually passed in June 1994, seven months after the collapse of talks between China and Britain on the 1994 and 1995 elections in Hong Kong that lasted 17 rounds.

Hong Kong needs an archives law before it’s too late

In September 1993, Beijing turned up the heat in the dispute by resurrecting a threat made by patriarch Deng Xiaoping in 1982 that China might take the territory before 1997.

He made the warning during his meeting with British prime minister Margaret Thatcher in Beijing on September 24, 1982.

It was the lead story in People’s Daily, in both the domestic and overseas editions, on China Central Television and pro-Beijing newspapers in Hong Kong.

Outlining China’s policy towards Hong Kong and its attitude to the question of sovereignty, the speech stated Beijing might consider an early takeover of the territory if there were major disturbances in Hong Kong in the countdown to 1997.

In a letter to Richard Gozney, Hurd’s private secretary, on November 21, 1992, Stephen Wall, private secretary to Major, summed up the prime minister’s meeting with US Ambassador Raymond Seitz the previous day.

Patten won fight with civil service over how to deal with China, files show

Major briefed the US ambassador about his discussion with Chinese vice-premier Zhu Rongji, who was known as China’s economic tsar, in London a few days earlier.

“The prime minister gave an account of the meeting with Zhu Rongji who had been pretty hardline. The Chinese tend to see the UK (and the US) as trying to subvert China,” Wall wrote. “Some of our sinologists were very cautious about the policy we were pursuing but Chris Patten could not have gone for anything less. ”

Contacted by the Post for comment, Patten said he was not going to comment on each batch of British records that came out.

“We should declassify all the Hong Kong papers in the 1990s and earlier. I very much hope that we will be able to see China’s papers too,” he said. “I am very happy for the record to speak for its actions in the light of what actually happened.”