Hong Kong’s film and TV industry after 40 years of China’s opening up and reform: once ‘Hollywood of the East’, does future now lie in being mainland’s supporting cast?

- Mainland China’s movie and television business now far outweighs Hong Kong’s in output, viewers and box office takings

- Hong Kong helped get the industry north of the border on its feet in the 1980s and 90s. Does the city’s future success lie in integration or staying distinct?

The past 40 years of reform and opening up in China have not only been about massive investments, infrastructure projects and turning the country into the world’s second largest economy. The years of the Cultural Revolution left mainlanders with little to watch on television and at the movies other than propaganda. As China opened up, Hong Kong television dramas and movies offered a glimpse of the outside world, city life and of what China’s big changes might bring.

When the mainland was ready to grow its own television and movie industry, Hong Kong producers and filmmakers played a crucial role, but the tables soon turned on the “Hollywood of the East”. Today, mainland Chinese television serials and movies are immensely popular in Hong Kong, and dominate in terms of output, viewership, and box office receipts.

Turning the tide in television

On a single Sunday in August this year, an episode of mainland Chinese television hit The Story of Yanxi Palace clocked up 530 million views online, setting a record.

Packed with drama, betrayal and intrigue, the 70-episode period drama won over audiences not only on the mainland, but also in Hong Kong, where it is 2018’s most popular drama aired by Television Broadcasts Limited (TVB), the city’s largest television broadcaster.

Costing 300 million yuan (HK$338 million) to produce, the series is about a maid who goes to work in the imperial palace to investigate her sister’s death and ends up a concubine of Emperor Qianlong.

Its huge success epitomises a major shift in the television and moviemaking scene over the past 40 years of China’s economic reforms and opening up.

Where mainland audiences once lapped up made-in-Hong Kong serials and movies, mainland productions now dominate in output, box office takings and viewership, including online.

Mainland blockbuster Wolf Warrior 2 unlikely to impress Hong Kong moviegoers, critics say

There is occasional tension and controversy over red lines – political taboos and censorship – as the mainland government has become more assertive.

And where once the themes and plots were scrutinised, today the political beliefs and public actions of artists can become the issue, and some are made to pay the price.

For the Hong Kong entertainment industry, the big question is whether future success lies in integrating with the mainland, or staying distinct.

Recalling the glory days, Hong Kong cinema veteran Tenky Tin Kai-man said: “We were the Hollywood of the East. A large number of talented individuals gathered in such a small place, competing with the finest, and selling to markets across Asia.”

The actor and producer, who heads the Federation of Hong Kong Filmmakers, was a teenager when he joined the industry in 1979. Now 56, he said he felt lucky to have been part of the golden era of the 1980s and early 1990s.

Between 1979 and 1999, Hong Kong made an average of 133 movies annually, peaking at 200 a year in 1992 and 1993. Meanwhile on the mainland, fewer than 100 movies were made each year in the 1980s and the cinema industry even declined in the 1990s when television prevailed.

Hong Kong filmmaker’s Toronto film festival showing reflects city’s international legacy

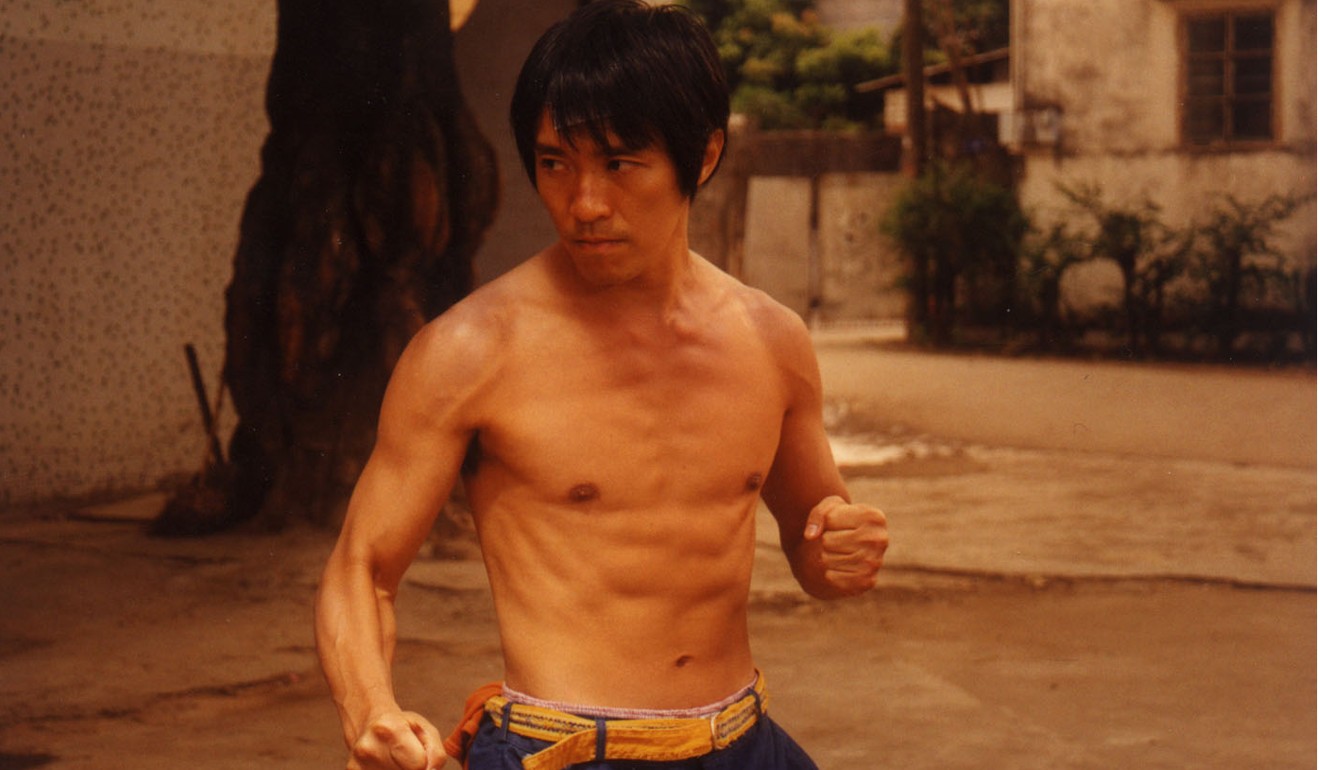

Dr Lo Wai-luk, a Baptist University associate professor specialising in the history of Chinese cinema, recalled that in 1983, the Jet Li martial arts movie The Shaolin Temple was watched by 50 million people on the mainland.

It was one of the few distributed widely in mainland cinemas in the 1980s because it was produced by state-funded Chung Yuen Motion Picture.

Many other Hong Kong titles by independent companies such as Cinema City and Golden Harvest, including those starring comedian Stephen Chow Sing-chi, circulated by videotape.

“Can you imagine people in Xinjiang gathering to watch a Stephen Chow movie by playing a shared tape?” Lo said.

Hong Kong movies had an appeal because of the mainland’s restrictions on the themes, plots and characters in movies made there.

Tin said: “Hong Kong could produce plots that mainland producers dared not make, for example, about cops committing crimes and officials being under fire.”

Ranking every Hong Kong film released in 2017, from worst to best

Hong Kong film as a window to the world

By the mid 1970s, the city’s three television stations were churning out drama series more than 100 episodes long, whereas on the mainland, the Cultural Revolution had not yet ended and it was still years before the earliest television series would be produced.

Through the 1980s and the 1990s, a wave of dramas from Hong Kong swept across the mainland.

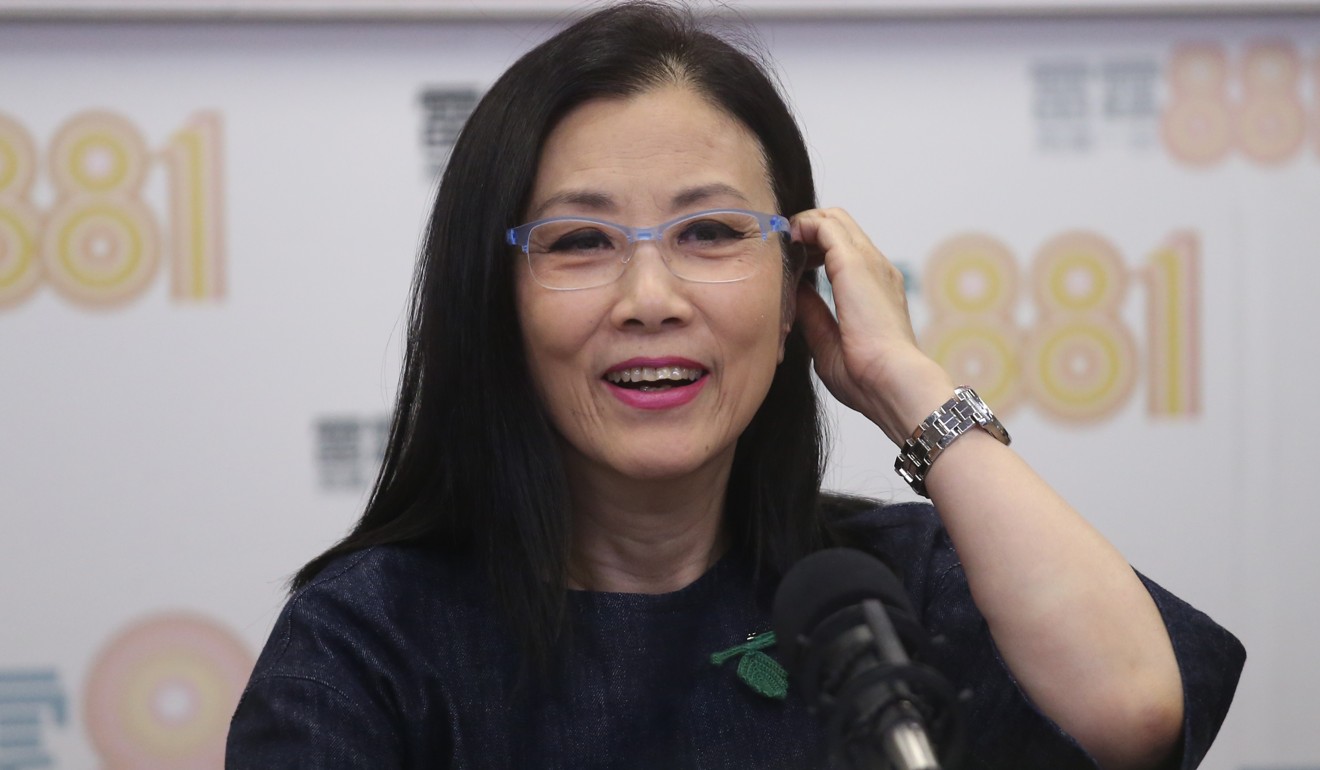

Actress and emcee Liza Wang Ming-chun, a Hong Kong television veteran of more than 50 years, remembered being invited to Guangzhou for her first live stage show there in 1979.

“There weren’t many private cars. The bridge across the Pearl River was full of bicycles during rush hour. And the people there were dressed in black, white, grey and blue – very modest in general,” said Wang, now 71.

“I could see their envy as they stared at us, the stars from Hong Kong.”

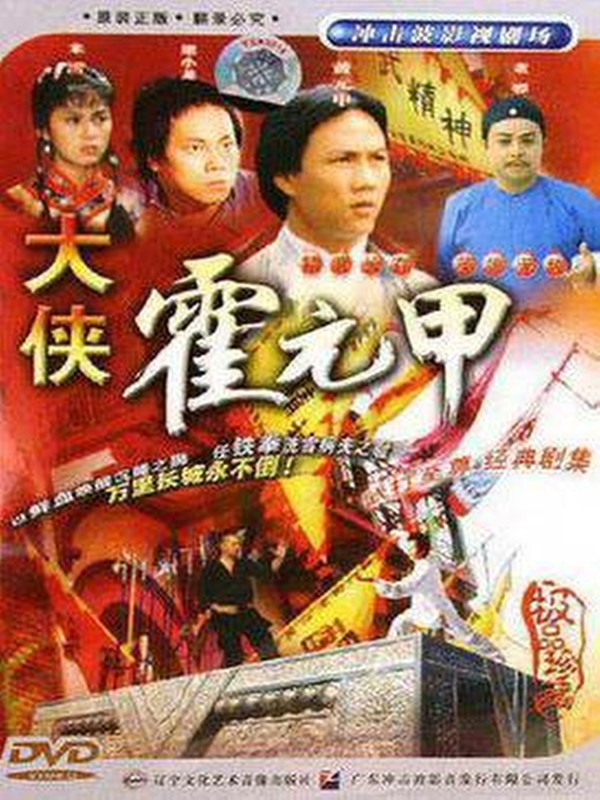

Rediffusion Television’s The Legendary Fok was the first Hong Kong drama imported and shown on the mainland, in 1983, two years after it was aired locally.

The hero, patriotic martial arts master Fok Yuen-kap, or Huo Yuanjia in Mandarin, was so popular that the 20-episode series was eventually broadcast across the country and even at prime time by state broadcaster CCTV.

Hong Kong filmmaker John Woo on the making of Manhunt, Hong Kong and Chinese cinema, and budget versus action movies

Drama serials adapted from the martial arts novels of the late Louis Cha Leung-yung followed, including The Legend of the Condor Heroes and The Duke of Mount Deer. Stars such as Felix Wong Yat-wah, Barbara Yung Mei-ling, Michael Miu Kiu-wai, Tony Leung Chiu-wai and Andy Lau Tak-wah soon became household names on the mainland.

A defining moment for the popularity of Hong Kong productions arrived with The Bund, starring superstar Chow Yun-fat and former beauty queen Angie Chiu Nga-chi in a sprawling tragic romance that has been dubbed “The Godfather of the East”. Its Cantonese theme song remains popular to this day among the mainland’s Mandarin-speaking audience.

“Hong Kong stood for novelty, affluence, fashion and opportunities for mainland audiences coming out of decades of isolation,” said Zhu Ying, a Chinese television culture studies professor at Baptist University’s film academy.

“Hong Kong dramas provided a window for mainland audiences to peek at the outside world.”

Lo said Hong Kong movies made in the 1980s by a new wave of independent production companies and featuring more outdoor, real-life locations, had the same impact.

Overt racism, bad education and less freedom - a Hong Kong filmmaker on her city

“Audiences on the mainland now could really see the city – for example, the shopping mall in Taikoo Shing where Jackie Chan was chasing after thieves in The Police Story series – as well as modern transport, the urban way of dressing, and business situations such as board meetings,” Lo said.

All these images of Hong Kong city life gave mainland film-goers, long fed anticapitalist propaganda, a glimpse of things to come in China. The “capitalist poison” label previously stuck on these movies was gradually removed.

“People on the mainland realised that outside the mainland there was a place with its own cultural system called Hong Kong, where they could find things not available at home,” Lo said.

But then the mainland began encouraging its own television and movie industry, and Hong Kong helped by supplying capital, professionals and know-how.

Wang said: “We made really big contributions to the mainland at the early stage of the reform and opening up process, bringing them techniques, art directors, machines, operational models and professional crews, because we knew much more than them.

“They didn’t stop at purchasing copyright. They would hire the whole team behind a programme to run the show till they grasped every bit of the craft.”

Controversial Hong Kong film Ten Years to spawn international versions in Thailand, Taiwan and Japan

‘Economic power confers cultural status’

The reversal of fortunes started in the 1990s, when new television stations mushroomed on the mainland, programme production boomed, and the country welcomed private and overseas capital for joint productions.

Mainland audiences soon had much more choice. There were still programmes about the Communist Party’s revolutionary history and ancient literary classics, but popular new shows such as The Aspiration and A Native of Beijing in New York showcased themes of migration and entrepreneurship.

Perhaps the last major Hong Kong drama serial to be a hit on the mainland was War And Beauty, a 30-episode TVB period production about four warring concubines of Emperor Jiaqing in the Qing dynasty.

The 2004 series was aired on the mainland two years later and is believed to have inspired a hugely popular new wave of period productions about palace intrigue and infighting.

In 2011, there were at least eight such series made on the mainland, including the 76-episode Empresses in the Palace, which drew so much attention that Hong Kong’s Cable TV picked it up to broadcast in 2012.

By 2007, mainland China had become the world’s largest producer of drama serials, cranking out 15,000 episodes every year.

Output was so massive that traditional television channels could not keep up, and by 2013, the internet had become a major platform. The following year 250 series with a total of 2,918 episodes were made by or for online streaming portals.

China’s film industry grinds to a halt because of Fan Bingbing tax scandal

Over in Hong Kong today, all three free-to-air broadcasters are relying increasingly on dramas imported from the mainland and South Korea.

“Things have changed now that the mainland has acquired its own level of chic and fashion and technique in producing its own sophisticated dramas,” said Zhu of Baptist University. “The mainland has aggressively rebranded itself as the new land of opportunity. Economic power confers cultural status.”

Over the past decade, a number of popular mainland dramas have been directed or co-directed by Hong Kong directors.

“The mainland has a lot of space, talent and capital,” Liza Wang said, pointing out that the sprawling Hengdian studio complex in Zhejiang province had full-size replicas of ancient palaces for period dramas, something space-starved Hong Kong could not provide.

The mainland pays better too. “Some artists can earn several hundred thousand yuan by singing a few songs. This is unimaginable in Hong Kong,” Wang added.

Romance returns to Chinese cinema – but off screen, the film industry is mired in relationship dramas

Walking the tightrope of censorship

The Hong Kong movie industry has noted the talent drain, Tin said.

“The mainland market has yet to reach its peak,” he said, adding that the big money was not only for stars but also backstage crews, with strong support for the cultural industry from local governments.

Last year the mainland’s total box office takings reached a record of 55.9 billion yuan, almost 3.5 times that in Hong Kong.

But access to the mainland market has been difficult for Hong Kong productions, because China sets a quota of 64 to 74 imported movies per year.

However, joint productions offer the city’s moviemakers a way in. An agreement treats movies co-produced by companies from the two sides as domestic productions and gives Hong Kong producers 35 per cent of ticket revenue, instead of just 15 per cent. The agreement was part of the Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement (CEPA) signed between the mainland Chinese and Hong Kong governments in October 2003 to boost the city’s economy, when it was struggling to recover from a downturn following the Sars epidemic that year.

Over the past 15 years, the proportion of joint productions leapt from about 15 per cent to over 60 per cent of all Hong Kong output. Three of the top 10 movie blockbusters on the mainland were joint productions, which earned between 2.44 billion yuan and 3.65 billion yuan.

But the issues of taboo subjects and censorship remain.

“Red lines have always existed,” Tin said. “We don’t know where they exactly are, or when and against whom they will be used.

He said many movies had not managed to clear mainland censors over the years, and there was nothing anyone could do about it.

Hong Kong film industry’s fake money fears eased as monetary authority pledges to streamline application process on prop use

The result, he said, was that some Hong Kong producers adopted self-censorship, while others planted a few scenes they hoped the nitpicking censors would snip quickly and clear the rest of the movie.

When the authorities are displeased, their wrath is plain.

Taiwanese artists who openly supported students taking part in the “sunflower movement” protests against a services trade deal with the mainland in 2014 were severely criticised by state-owned media on the mainland as “smashing the rice pot they eat from”.

Punishment may range from a torrent of online bashing, to having contracts cancelled, a heavy reduction of screen time, or outright bans on performing on the mainland.

Singer-songwriter Anpu, award-winning director Wei Te-sheng, television host Kevin Tsai Kang-yung, and actor Leon Dai Li-jen have all paid a price.

Several Hong Kong artists met the same fate for supporting civil disobedience protesters in the Occupy movement, which shut down several business areas for 79 days in 2014.

They included singers Anthony Wong Yiu-ming and Denise Ho Wan-sze, who participated in the protests, and actors Chapman To Man-chat and Anthony Wong Chau-sang, who defended the demonstrators and criticised authorities.

Hong Kong film with Chinese characteristics?

Hong Kong comedian Wong Cho-lam, who has been active on the mainland since 2010 and set up his own studio there two years ago, said: “Nowadays contracts stipulate that if an artist or director causes damage to the production as a result of personal ethics, a criminal offence or political stance, the person will be liable.”

Wong, who sits on the political advisory body to the Guangxi government, was frank about pressure on cross-border artists.

“Some Hongkongers might put me under fire when I say I am a patriot, but if I refrain from saying so, some patriotic audiences might put me under fire,” he said.

Wong said he did not believe in joint productions as a way to keep Hong Kong’s movie industry thriving.

“I would rather make a movie either catering to the mainland, or in the Hong Kong style,” he said. “Why don’t we make something with a genuine taste and character of Hong Kong and introduce it to the mainland audience?”

Lo of Baptist University did not think joint productions would destroy the flavour of Hong Kong movies.

“Project Gutenberg was loved by mainland audiences,” Lo said, referring to a film released in October.

Made with investments and stars from Hong Kong and the mainland, the movie had Hong Kong scriptwriting and directing. Lo did not think the story about a frustrated painter who becomes a master banknote counterfeiter could have come out of the mainland or Taiwan.

UK spends aid too much money on Chinese film industry, not enough on world’s poorest, say lawmakers

“Hong Kong movies must find their own ethos,” Lo said. “Hong Kong movies do not have to seek distribution on the mainland if they can manage the budget and attract local audiences.”

Tin thought Hong Kong artists should continue working to remove the negative labels on their peers who have run foul of mainland authorities.

“To isolate or ground someone who is found politically incorrect will cause a chilling effect, which is unhealthy,” Tin said.

“To some extent, Hong Kong movies have lost their charm because we agreed to compromise our professional judgment and expertise.”

Liza Wang believed Hong Kong’s younger talent in television and movies had a land of opportunity in the “Greater Bay Area”, which has close to 70 million people who understand Cantonese.

Beijing’s vision is to connect Hong Kong, Macau and nine cities in Guangdong province and create an innovation and technology powerhouse to rival California’s Silicon Valley.

“There are so many people there who can understand our language and enjoy our work,” Wang said. “And the market size is not as huge as the whole mainland so it should be suitable for young talent to get some exercise.”

In March, Wang, kung fu star Jackie Chan and veteran comedian Eric Tsang Chi-wai were involved in forming a committee to help Hong Kong artists make their way into the mainland.

While Wang said she respected those who held firm to their political beliefs, she also said: “If you want to tap into a certain market, you must think twice about whether you should test the rules there.”

Additional reporting by Jane Zhang

Inside China podcast: 40 years of economic ‘reform and opening up’