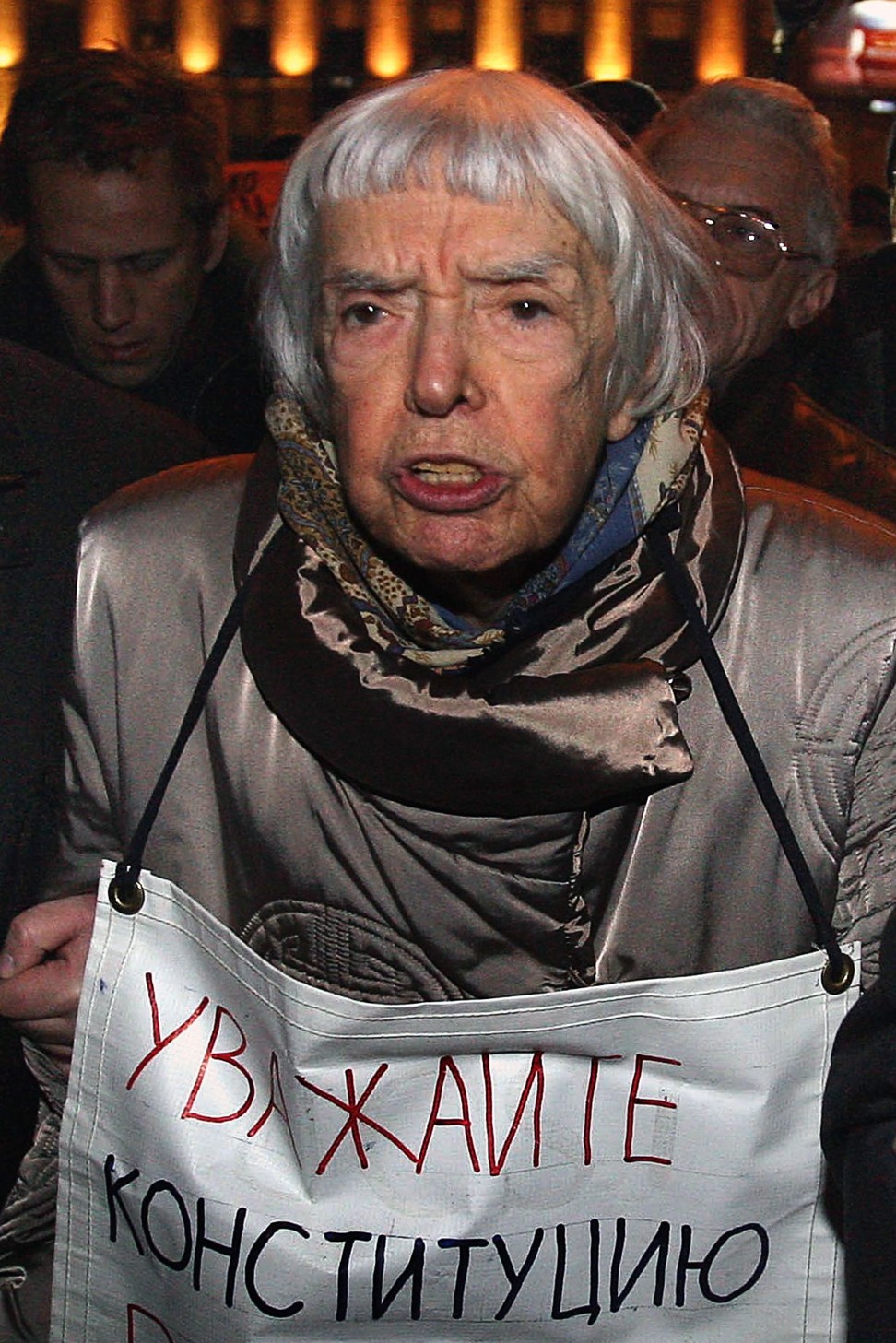

‘Repression makes you stronger’: Lyudmila Alexeyeva, grand dame of Russian human rights movement, dies at 91

- She received death threats, was accused of spying for the West, interrogated by the Soviet KGB and forced into exile for 16 years

- She came of age as a dissident in the late 1960s, spurred by the arrest of writers and other intellectuals under Brezhnev

Lyudmila Alexeyeva, the grand dame of Russia’s human rights movement, who championed democratic reforms under Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev and later became a leading antagonist to President Vladimir Putin, died on December 8 at a hospital in Moscow. She was 91.

Her death was announced by Russia’s Presidential Council for Civil Society and Human Rights, which did not give a cause.

“This is a loss for the entire human rights movement in Russia,” said council head Mikhail Fedotov. In 2012, he had likened her to “a lighthouse standing on a rock and showing you where to go and not to go”.

Organised in defence of Article 31, the Russian constitutional provision that, at least in theory, guarantees the right to assembly, the rally ended with Alexeyeva and about 50 other protesters detained by police as pro-Kremlin activists danced to holiday music nearby. Expecting to be arrested, she had already ordered meat pies to her flat, where a New Year’s party was raging by the time she arrived home from the police station at 11pm.

Standing just over five feet tall, Alexeyeva was a diminutive yet forceful opponent of the Kremlin for half a century, nimbly shifting from the clandestine samizdat of the Soviet era to blog posts in the digital age. Raised amid the terror of Stalin’s purges, when some of her neighbours were arrested and whisked away by the Soviet secret police, she came of age as a dissident in the late 1960s, spurred by the arrest of writers and other intellectuals under Brezhnev.

As a typist for the Chronicle of Current Events, an underground periodical that reported on human rights violations, she was sometimes called into KGB headquarters for questioning, and once stuffed eight copies of the Chronicle into her bra to avoid the prying eyes of interrogators.

On her way to be interviewed by the secret police, The New York Times reported in 2010, she would buy a ham sandwich, an eclair and an orange – luxuries in the 1970s Soviet Union.

“They reacted very nervously when they started to smell ham,” she told the Times. “Then I would start eating the orange, and the aroma would start dissipating through the room.”

“That’s how I amused myself,” she said. “It was a way to play on his nerves.”

Alexeyeva was perhaps best known as a founding member of the Moscow Helsinki Group, often described as Russia’s oldest human rights organisation. Initially led by physicist Yuri Orlov, the group was formed in May 1976, nine months after the Helsinki Accords were signed in Finland by the United States, the Soviet Union and 33 other countries.

Published in full in Pravda, the accords featured a section noting that “the participating states will respect human rights and fundamental freedoms, including the freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief, for all without distinction as to race, sex, language or religion.” Alexeyeva, along with Orlov and the group’s nine other founding members, set about ensuring that when the Soviet Union fell short of its promises on human rights, the rest of the world would hear about it.

I don’t know of a single person who works with me who would stop doing what they are doing because of threats

The group smuggled 195 reports out of the country, including a document Alexeyeva assembled from a fact-finding mission in Lithuania, where she catalogued abuses against a group of teenage boys who refused to slander a Catholic dissident.

Not surprisingly, it also earned the ire of the Kremlin, which sent members of the Moscow Helsinki Group to prison, to forced-labour camps or, in the case of Alexeyeva, to exile abroad. She worked in the United States, writing books and testifying to institutions including Congress and the State Department on Soviet affairs before returning to Russia in 1993, less than two years after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Alexeyeva helped resurrect the Moscow Helsinki Group, which reasserted itself as a human rights watchdog under Putin, a former KGB officer who was elected president in 2000. While she served on his human rights advisory council, she became a fierce critic of his handling of the Second Chechen War, as well as his government’s stifling of dissent and political opposition.

After the 2003 parliamentary elections, in which the Putin-allied United Russia party swept liberal lawmakers out of office, Alexeyeva said she told Putin: “We don’t have elections any more, because the results are decided by the bosses and not the people.”

Yet she remained guardedly optimistic, insisting that younger generations gave her hope, even as she acknowledged she would probably not live to see Russia became “a democratic state with the rule of law.”

“Repression makes you stronger,” she said at a Moscow human rights forum in 2012. “We lived through Soviet power,” she added, “and we will live through this power.”

Lyudmila Mikhailovna Alexeyeva was born in Yevpatoria, a Black Sea port town in Crimea, on July 20, 1927. Her father was an economist who was killed in World War II, and her mother was a mathematician; the family moved to Moscow when she was 4.

Alexeyeva studied archaeology and history at Moscow State University, receiving a bachelor’s degree in 1950, and did postgraduate work at the Moscow Institute of Economics and Statistics, where she received an advanced degree in 1956, according to the National Security Archive at George Washington University.

Alexeyeva taught high school history in Moscow before serving as an editor at Nauka, a scientific publishing house. After signing a letter in defence of Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel, writers who were convicted of anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda in 1968, she lost her job and was expelled from the Communist Party.

Her own books, written in the United States, included “Soviet Dissent: Contemporary Movements for National, Religious and Human Rights” (1985), which Los Angeles Times reviewer James Mace called “the best treatment of Soviet dissent yet available in any language,” and, with Paul Goldberg, “The Thaw Generation: Coming of Age in the Post-Stalin Era” (1990).

Her marriage to Valentin Alexeyev ended in divorce. She later married Nikolai Williams, a mathematician. Survivors include two sons from her first marriage; five grandchildren; and three great-grandchildren.

In recent years, Alexeyeva watched, aghast, as colleagues such as Stanislav Markelov, a 34-year-old human rights lawyer, were shot and killed on the streets of Moscow. But she said such attacks had little impact on her work.

“I don’t know of a single person who works with me who would stop doing what they are doing because of threats,” she told Associated Press in 2009, after the killings of Markelov and a journalist, Anastasia Baburova. “If I stopped what I am doing now, life wouldn’t be interesting to me.”