Is North Korea’s Kim Jong-un serious about peace or just playing everybody (again)?

Pyongyang rang in the new year with open arms to its neighbours, but analysts are sceptical whether the recent play is anything more than subterfuge

South Korean President Moon Jae-in immediately responded by proposing high-level inter-Korean talks to discuss its participation on January 9, to which the North has since agreed, marking the first time such talks will have taken place since December 2015, and signalling a personal triumph for Moon, who has made getting the North to the negotiation table his presidential raison d’être.

In a nuclear crisis over North Korea, why ignore the South?

North Korea’s head of inter-Korean affairs, Ri Son-gwon, then announced on state television that Kim had ordered the reopening of the Seoul-Pyongyang hotline, which North Korea severed two years ago, to discuss the participation of its athletes. Ri added that Kim welcomed Moon’s support in the matter.

Why does Seoul routinely low-ball North Korea’s missile range?

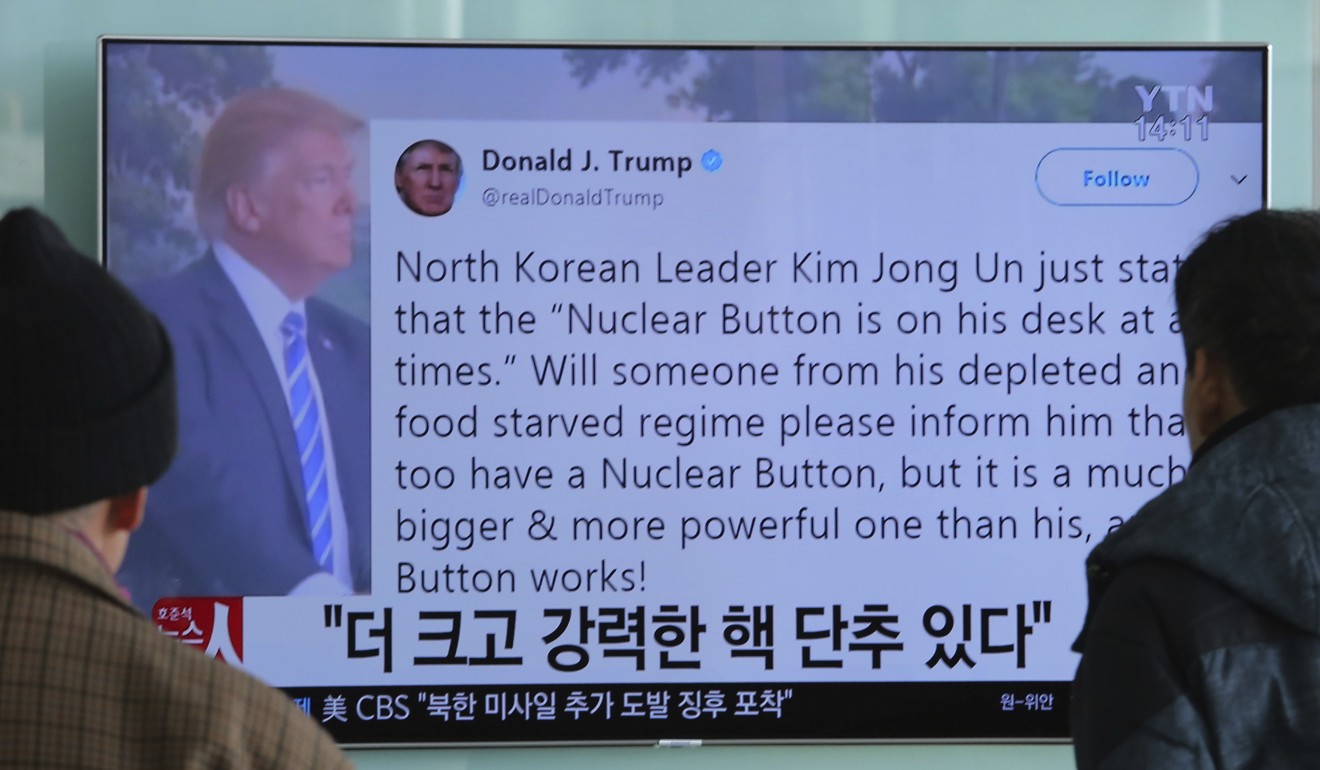

But Moon staunchly avoided the sabre-rattling in which Kim and Trump have so freely indulged over the past months. Since taking office on May 10, he has seen the regime snub any effort at rapprochement, repeatedly threaten to start a nuclear holocaust and rapidly develop its weapons programmes by testing four anti-ship missiles, nine ballistic missiles and a thermonuclear bomb. Tensions are subsequently the highest they’ve been since the end of the Korean war. On Sunday, Admiral Mike Mullen, former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said the United States is “closer to a nuclear war with North Korea than ever”.

Yet Moon has remained calm and ready, and now at the eleventh hour, his composure has apparently paid off. On Thursday, the United States and South Korea agreed to postpone military exercises – involving hundreds of thousands of troops – although US officials insisted the move was to focus on security during the Winter Olympics and not a sign of a softened stance on Pyongyang.

As the work of untying this geopolitical knot begins – some analysts say the North’s about-face may have nothing to do with Moon’s strategic patience, and the true cause may suggest that the regime in fact only responds to more stick and less carrot.

Between Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un, South Koreans wonder who is crazier

“It seems to me that sanctions played a role in compelling the North Korean leader to act,” said Choi Jin-woo, a political science and international studies professor at Hanyang University, who added that the subsequently severe economic impact has had a far greater effect than Moon’s kindness. “After the September nuclear test, sanctions were strengthened and I think now it’s working. The sanctions bite.”

It’s time to educate the Chinese public about the nuclear threat next door

Another reason to believe that the North hasn’t had a change of heart is this year’s address is not markedly different from the previous two that Kim has given. In 2017, he talked about the need for all Koreans to “join forces” and “open a great pathway to autonomous unification”. The year before that, he delivered his first New Year’s address on the heels of former president Park Geun-hye’s election, proclaiming that the two sides must cease confrontations to bring about reunification. Both times, he followed these warm overtures in the months that came with bomb and missile tests, refusals to negotiate, periods of silence and copious death threats.

This is why the United States is focused on cutting off North Korea’s oil supply. As H.R. McMaster, Trump’s national security adviser, said on December 9, “You cannot shoot a missile without fuel.” But the strategic gains come with a moral cost. “A full oil cut-off would certainly dramatically reduce the amount of domestically grown food available to the civilian population,” David von Hippel, a senior associate at the Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability, told NBC News last week.

He added that unless other countries compensated by giving the regime food, “this would likely lead to famine”.

What the next Korean war will be like

Besides which, there’s no guarantee an oil embargo would even work. Even if China and Russia signed off on one, which seems unlikely, that wouldn’t ensure supply lines to Pyongyang would stop flowing. According to Koo Kab-woo, professor of international politics and economy at the University of North Korean Studies in Seoul, “An oil embargo won’t work because nowadays there are suppliers to North Korea from Russia and China, private actors who will try to supply oil to North Korea because of the profit.”

And supposing China and Russia did sign off on an embargo, and these private actors could be thwarted, Pyongyang might just hunker down in response. In any case, the recent political climate change seems more tied to crushing international sanctions than kindness.

These shadows darken the path to progress Moon is intent on taking. Lines of communication may have reopened, but the escape velocity needed to slip the pull of war is still beyond reach, and many analysts remain deeply sceptical as to whether Pyongyang’s recent play is anything more than subterfuge, intended to bide time to continue building its arsenal.

“I don’t think President Moon has come to terms with the fact that North Korean policy is and always has been to conquer South Korea,” said Bradley K. Martin, author of Under the Loving Care of the Fatherly Leader: North Korea and the Kim Dynasty. “I see no reason to think that’s about to change. When the North plays nice with the South it’s always temporary and tactical.” ■