Who gained the most from Hong Kong’s colonial era: Britain, China or the city?

A brief history of the British Empire’s control shows many inside – and outside – the city benefited from its rule

Hongkongers are often said to be too practical to worry about history, let alone argue whether colonialism here was good or bad.

It’s hard to imagine something along the lines of the recent controversy over the “ethics of empire” project at Oxford, even less a demand to demolish statues or rename roads and buildings. But that has not stopped colonialism from appearing in local political discourse, more than 20 years after the return to Chinese sovereignty.

Judging empires: Was Japanese rule in Taiwan benevolent?

So-called Beijing loyalists and self-proclaimed pro-establishment figures blame colonialism for the failure of Hong Kong people, especially youth, to embrace the “motherland”.

It’s an odd claim. To be sure, the colonial government worked hard from the late 1960s to build a sense of local identity, including through education and programmes such as the Hong Kong Festival and the Keep Hong Kong Clean Campaign. But if colonialism is why so many local people increasingly identify themselves as Hongkongers first and Chinese second (if at all, for some), then wouldn’t this have been even more so the case in the immediate years after 1997, rather than two decades into reintegration with the mainland?

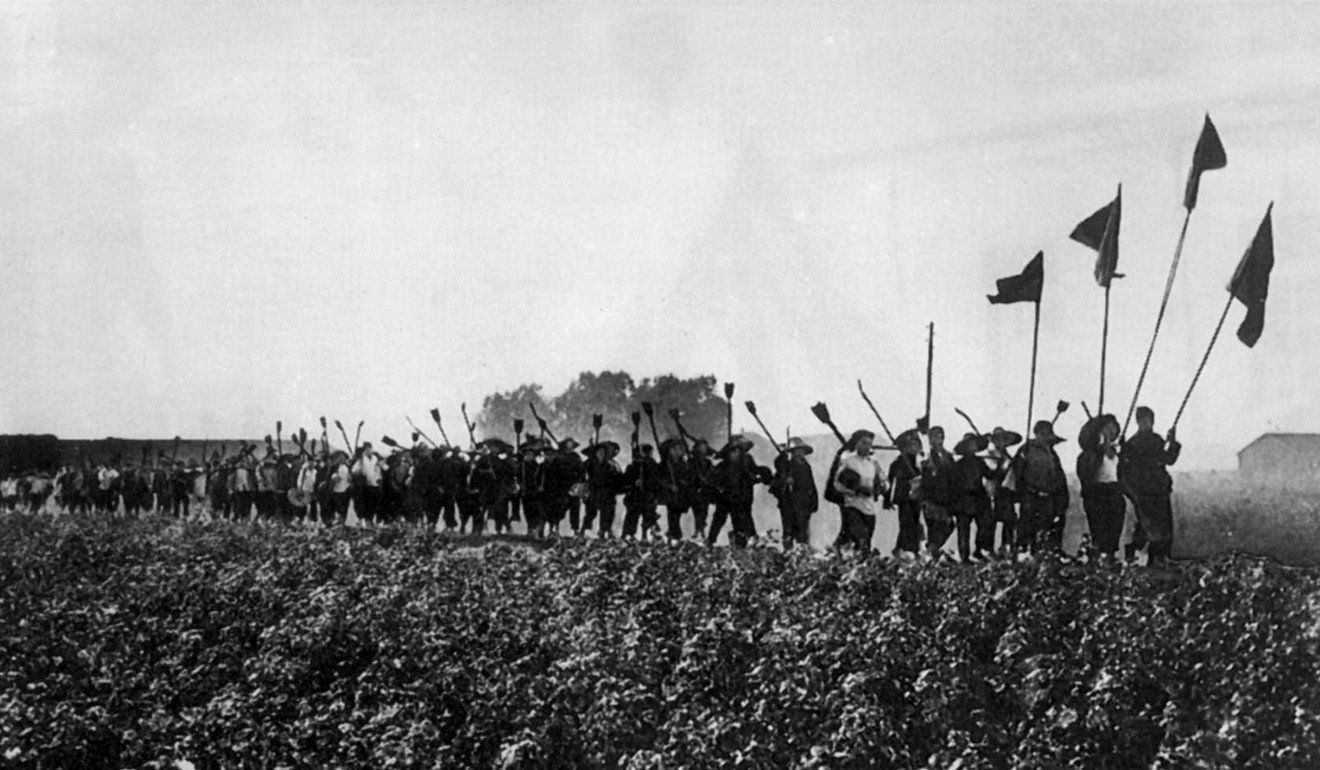

These loyalists also assume that learning more about Chinese history will help Hong Kong’s young people associate more closely with China. But surely this would only make youngsters even more aware of the fact that, without colonial Hong Kong, modern China might have turned out very differently. They would learn how, from this small colony, patriotic Chinese were able to play a central role in Chinese history: ousting the Manchus in the 1911 Republican Revolution, supporting nationalist and labour movements in the 1920s, and contributing to the Chinese war effort after the Japanese invasion in 1937.

Trump’s big button to Thai penis whitening: hail the emperor, without his clothes

They would also learn how colonialism saved Hong Kong from the tragedies of the “anti” campaigns of the 1950s, the Great Leap Forward and the Great Famine, and the Cultural Revolution. So, too, would they learn that emigrants who returned to China from Australia, North America, or Southeast Asia almost always came through Hong Kong, as did remittances from overseas Chinese. And that Hong Kong investors were greatly responsible for China’s dramatic economic transformation in the late 1970s.

On the other side, or, rather, one of the other sides, we have protesters who wave the colonial flag (and sometimes even the British flag) at rallies and who maintain that Hong Kong would be better off it were still a British colony and urge that it be returned (as if Britain isn’t having a hard enough time negotiating Brexit). They might be surprised to learn that one of the main reasons Hong Kong remained a colony as long as it did was because the same Communist government that proclaimed its determination to ending imperialism across the globe not only tolerated but encouraged Hong Kong’s colonial status.

Joseph Stalin once mocked Mao Zedong for allowing this to happen. Whereas Chiang Kai-shek, supported by Franklin Delano Roosevelt, had considered recovering Hong Kong during WWII, Mao had no such plans. He may have once referred to Hong Kong as “that wasteland of an island”, but Mao was well aware that it could be of great use. He was right. During the Chinese civil war from 1946 to 1949, the colony was a base for recruiting and training cadres and for spreading Communist propaganda – not only within Hong Kong and in the mainland but among overseas Chinese communities.

After the establishment of the PRC, Hong Kong served as a window to the capitalist world, a base for importing goods that the new China couldn’t even hope to produce, and a source of valuable foreign exchange. British officials in London and in Hong Kong were well aware that China could recover Hong Kong easily, even if the new government didn’t seem interested in doing so.

Singapore and Hong Kong may be different, but there’s no debate on what the British did to India

They might not all wave the colonial flag, but many Hong Kong people see the past few decades of colonial rule as a sort of golden age.

To be sure, Hong Kong came out better than almost any other former colony, British or otherwise. Governor Murray MacLehose’s tenure, from 1971 to 1982, saw a massive expansion of government spending and intervention, often against the wishes of the local business community: more and better public housing, medical and health services, education, labour legislation and social welfare, transport and infrastructure (including the Cross Harbour Tunnel and the MTR), arts and culture, and of course the Independent Commission Against Corruption. There is little reason to doubt the transformative and positive effects of these measures.

However, as files in Britain’s National Archives declassified over the past decade reveal, many of these reforms were implemented to help Britain hold on to Hong Kong for as long as possible. During the 1967 riots, the British realised that Hong Kong could not be defended if China ever wanted to take it back, and that it would eventually have to be returned.

MacLehose called his administration “a government in a hurry”. The hurry? To make Hong Kong such a different and better place from the rest of China that it would be difficult for the PRC to rule, at least not without British help – a kind of “one country, two systems” model, though definitely not the one Deng Xiaoping had in mind.

Hong Kong, like India, needs to remember the truth about British colonialism

None of this is to suggest that Hong Kong’s colonial history doesn’t need to be questioned and challenged. As local journalists, scholars and students are learning from the recently declassified files, there is plenty of room for constructive, well-informed debate. ■

John Carroll is professor of history and associate dean in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Hong Kong and author of ‘Edge of Empires: Chinese Elites and British Colonials in Hong Kong’ and ‘A Concise History of Hong Kong’