Forget ex-CIA agent Jerry Chun Shing Lee: fears over Chinese spies are overblown

The excitement over the ex-CIA officer accused of spying for China hides a less glamorous truth – that most of Beijing’s ‘foreign agents’ are engaged in work that is banal, costly … and largely pointless

Whatever the truth surrounding the case of Jerry Chun Shing Lee, the ex-CIA officer arrested by US authorities last week and accused of having spied for China, we can be sure of one thing: he was quite unlike the agents typically used by the Chinese Ministry of State Security (MMS).

If the allegations against him are true, then Lee was unusual in that he was actually useful to his handlers – unlike the vast majority of the MSS’s foreign agents.

Lee was stopped after flying into John F. Kennedy Airport from Hong Kong and arrested on a single count of illegally possessing classified information – the real names and contact details of covert CIA sources, the locations of covert facilities and meeting locations. If that wasn’t enough (he faces 10 years in prison if found guilty), media reports have speculated his case is linked to one of the US government’s most serious intelligence failures of recent years – a years-long espionage operation by Beijing that led to the death or imprisonment of 18 CIA informants.

That would put him in a completely different league to the large corps of agents – American and other nationalities – in China who are on the MSS payroll (at great expense), yet whose work is so insignificant many do not even realise they are committing crimes that could earn them life sentences in their home countries.

Usually, these agents don’t get caught, but occasionally they do, and the curtain is lifted ever so briefly on a world far less sophisticated – and certainly less glamorous – than the average drug store espionage novel.

Spies and a magic weapon: why are Australia, NZ so suspicious of China?

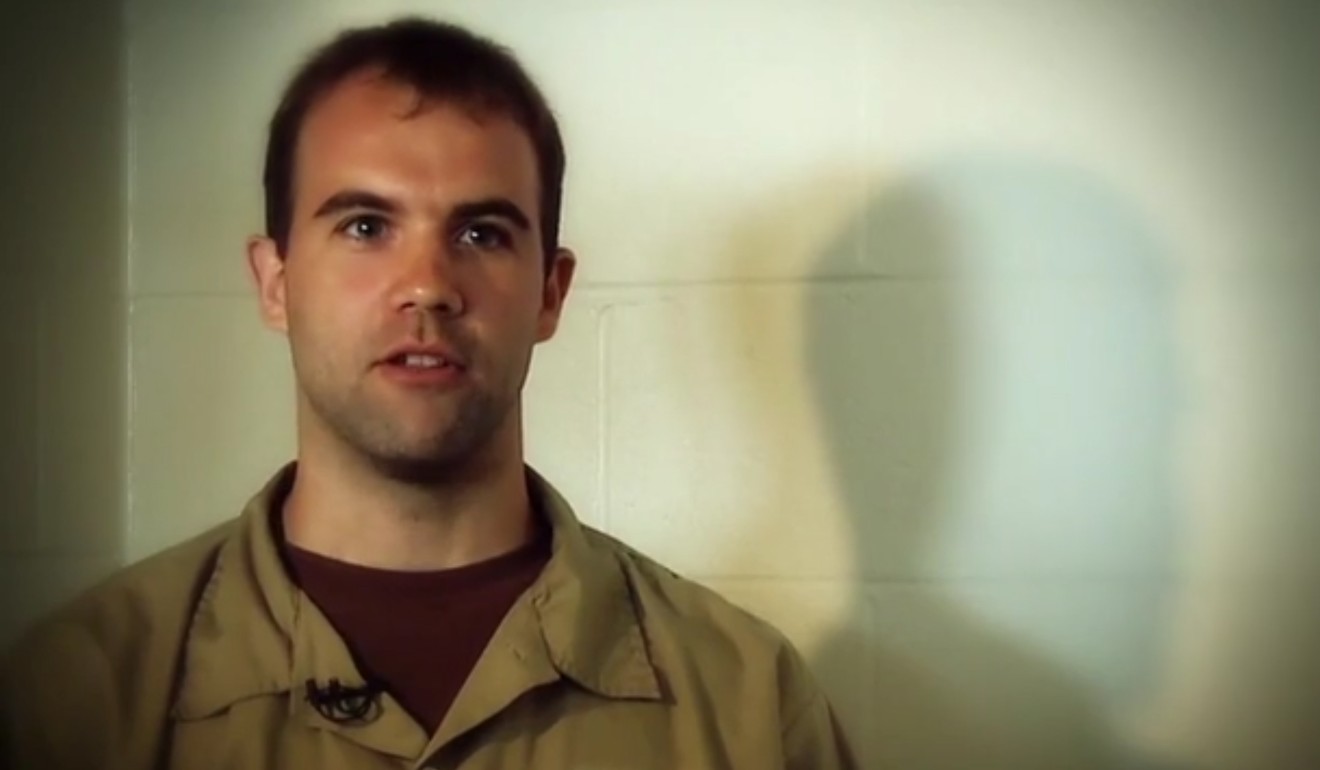

Take, for instance, the young oaf Glenn Shriver who applied for a job at the CIA at the request of – and while being in the pay of – the MSS. Shriver, a graduate in international relations who had moved to Shanghai to study Chinese, had been approached by the MSS in 2004 when he answered an advert to write a paper about Sino-US relations. An MSS agent calling herself “Amanda” contacted him to praise his paper and offer him payment for it – reportedly as little as US$120. As Amanda developed her relationship with Shriver she came to introduce him to other MSS agents, who gradually worked up to encouraging him to apply for jobs with the US government. After three unsuccessful attempts by Shriver to join the US Foreign Service and CIA – for which Shriver was paid a total of US$70,000 – the CIA and FBI caught up with Shriver and in 2011 he was sentenced to four years in prison.

Pedestrian as Shriver’s case may seem, it’s positively James Bond territory when compared to the mundane world of many MSS “foreign operatives”.

One such agent serves the MSS by producing reports which she researches by Googling the subject under discussion, and occasionally asking other foreigners she meets in her day job for their opinions, which are faithfully reported as being “the American view” or “the German view” depending on the nationality of who she speaks too. Another agent, in addition to providing pointless news updates, corrects the English language essays that MSS employees prepare as part of their training programme. The reason these individuals don’t get caught is that rather than hacking into the National Security Agency’s mainframe or doing anything else that might attract the attention of serious counter-intelligence officers, they are simply wasting time – their own and that of their handlers’.

Most foreign operatives in the above category are under 40, active on social media, and have a record of having applied to and been rejected by large or well-known organisations: government institutions, major banks, newspapers, accountancy or legal practices and so on.

WATCH: Curbing of US spy powers is ‘historic’: Edward Snowden

The Trump presidency and the prevalence of extreme views on social media has been helpful for Chinese recruiters, as some young Americans feel justified in working for a foreign power. And whereas the hope of landing an important job after graduating might once have given expression to their ambitions, a year or two of rejection makes it more likely that they will be receptive to appreciation from other quarters. Chinese recruiters can be very flattering indeed to people like this.

They hope that if they cast the net wide enough, they might find something useful, but this is awfully expensive and time consuming. Shriver, remember, cost the Chinese government US$70,000. In return, he gave back nothing of value.

Dear China, I am a white guy and not a spy

Jerry Chun Shing Lee was different for a variety of reasons. Obviously, his former career with the CIA would have made him a prized asset for the MSS, especially because he is said to have held a grudge against the agency after being overlooked for promotion.

Lee was not only older and far more knowledgeable than the type of useless agent referred to above, his ethnicity was significant, too – the MSS expects to find its most committed foreign agents among ethnic Chinese.

Lee also sticks out for something he didn’t have: an internet profile.

Chinese intelligence excels at number-crunching and internet profiles on social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter help the average MSS employee identify potential operatives without even leaving the office.

Even LinkedIn is seen as a handy tool for spy agencies: fake accounts can be set up relatively easily, though the amount and quality of information is scarce.

Most Western spy agencies are well aware of this. Germany’s intelligence agency, the BfV, has perhaps done the most comprehensive work on the subject. BfV researchers gave the example of “Lily Wu”, a member of a Chinese think tank who was able to “connect” with various German businessmen and politicians. Her only flaw was that she did not exist. And there are many like her: retired (or fired) civil servants in the United States or Britain have connected with potential business partners on LinkedIn, believing their experience and talent has been recognised and that they might win a consulting contract for a big multinational company if they keep the dialogue with their new LinkedIn friend going. But some of these business partners are foreign agents who convince the retirees to hand over details that expose or at least identify other civil servants who are still active.

Such efforts rarely lead to anything of great use to Chinese intelligence gatherers, and in any case counter-espionage work by many Western countries is effective.

Indeed, this is indicative of a wider malaise in Chinese spycraft – that its recruitment efforts in the West have been traditionally clumsy. Ignore the claims of many Western ex-spycatchers who say their work has been hampered by diversity targets and a push against racial profiling. This is probably prejudice talking – there has been no noticeable decline in the success rates of Western intelligence agencies.

The weak spot for Western powers is in China itself: it is much more difficult for the US to police treacherous behaviour by US citizens if they live in China. Hence cases like Shriver’s.

China has been moderately successful in recruiting non-ethnic-Chinese spies and other non-Chinese, ex-CIA or ex-government employees who, like Lee, are disgruntled. Last year, the former CIA officer Kevin Mallory was charged with passing top secret US government documents to Chinese intelligence in exchange for US$25,000.

At the same time, China has recently been taking a more pushy approach to counter-espionage against the US – exemplified by the events of one evening in January 2016, when a US consulate worker in Chengdu was forced into a van by plain-clothes police. He was interrogated for hours and allegedly filmed confessing to spying for the US. He was handed back to US officials the next day and shortly after left China.

This was odd. The general rule is for countries to tolerate espionage by people with diplomatic immunity. Only in rare cases are diplomats caught. Businessmen or other non-diplomats who engage in espionage are at much greater risk, but in the Chengdu incident the detainee was a civil servant. In response to this incident the US threatened to deport Chinese diplomatic staff who had been spying, and since then there seems to have been no further action against US diplomats. The Chengdu incident smacks of frustration at local station level on the Chinese side – certainly such behaviour is not the hallmark of a cunning or measured approach.

OVERBLOWN

There is also an element of exaggeration regarding the 18 CIA agents in China who were uncovered between 2010 and 2012 and subsequently executed or imprisoned – a case that some media outlets have linked to Lee. The story makes for sensational reading, but its effect on US intelligence gathering has been overblown – there were and are far more Chinese providing good intelligence to the CIA than Americans providing useful intelligence to the MSS. Indeed the Ministry of Public Security, rather than the MSS, has been the rising star in China’s espionage triumvirate (the MSS, the PLA’s intelligence service, and the MPS). For two decades the MPS was ignored by foreign counter-intelligence agencies, but its internal security budget expanded after 2010 and it took control of national databases and urban surveillance.

Other organisations, such as Xinhua and the Ministry of Education (which runs the Xue Lian organisations overseas) are supposed to gather intelligence but in reality are only able to gather large amounts of raw information. This data does not usually translate into usable intelligence and ties down analysts back at base who have to sift through it all.

NON-BELIEVERS

Which brings us back to the problems faced by Chinese intelligence: it is still extremely difficult to recruit any non-Chinese who believes in their work.

The best agents are those that want to serve because they are committed, not people who are in it for spare cash or because they are feeling disillusioned with life. The US has a history of attracting foreigners to its cause, as it has a history of assimilating people from all over the world. China has no such attraction, and will continue to be hobbled by this problem for some time.

The former Soviet Union, by contrast, managed to recruit foreign agents very efficiently – it talked up its noble socialism and talked down the purges and starvations, and attracted many British and American intellectuals.

When China cracks this problem and manages to propose an ideology with real attraction, the West will face a more serious threat. ■

Nicolas Groffman writes on China, practised law in Beijing and Shanghai, and is currently a partner at law firm Harrison Clark Rickerbys